A Groton memorial honors World War II submarine veterans and the more than 3,600 submariners who lost their lives during the conflict.

A Groton memorial honors World War II submarine veterans and the more than 3,600 submariners who lost their lives during the conflict.

The largest feature of the World War II National Submarine Memorial on Bridge Street is the conning tower of the USS Flasher (SS-249). The Flasher, built by Groton’s Electric Boat and commissioned in 1943, was credited with sinking the highest tonnage of Japanese ships (24 vessels and more than 100,000 tons) during World War II.

The memorial site also features a Wall of Honor with polished granite panels listing the 3,617 submariners who died in the World War II. A dedication panel at the center of the wall honors the submariners’ sacrifices and memory.

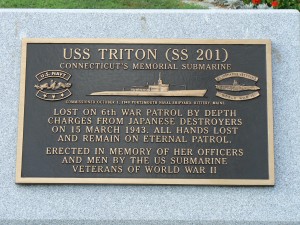

Another monument at the site honors the 52 submarines lost between January 1941 and August 1945. Bronze plaques list the name of the vessel and the date of its sinking.

Another monument at the site honors the 52 submarines lost between January 1941 and August 1945. Bronze plaques list the name of the vessel and the date of its sinking.

The submarines are also honored with engraved granite panels lining one of the memorial’s walkways. The panels list a submarine, the number of crew members killed and the date each sub was lost.

The submarine memorial began with the display of the Flasher’s conning tower in 1964 at a site on Route 12. In 1974, the Flasher was moved to its present, well-maintained location. The Wall of Honor was dedicated in 1994.

World War II submarine veterans are honored with a similar memorial outside the Naval Weapons Station in Seal Beach, California.

World War II submarine veterans are honored with a similar memorial outside the Naval Weapons Station in Seal Beach, California.

Sources: U.S. Submarine Veterans, Inc. brochure, submarinehistory.com

Milford honors submarine pioneer and local resident Simon Lake by displaying a submarine at a Milford Harbor marina.

Milford honors submarine pioneer and local resident Simon Lake by displaying a submarine at a Milford Harbor marina.

Simon Lake, a New Jersey native, lived in Milford between 1907 and his passing in 1945. Lake launched the first submarine to operate in open water, the Argonaut, Jr., in 1898.

Between 1909 and 1923, Lake built 33 submarines for U.S. Navy and also constructed vessels for European nations.

Lake’s last submarine, the two-man Explorer, was built in 1936 and was designed for civilian uses such as underwater research, mining and oil drilling, and wreck hunting and salvage. During underseas operations, the Explorer depended on a mother ship for air and power.

Divers entered the Explorer through the round hatchway. Peering inside the sub’s front windows reveals an array of switches, valves and chains.

Divers entered the Explorer through the round hatchway. Peering inside the sub’s front windows reveals an array of switches, valves and chains.

World War II reduced civilian demand for submarines, and the Explorer was stored in drydock and remained there until 1950. After years of neglect, the Explorer was placed on display outside Bridgeport’s Museum of Art, Science and Industry (today’s Discovery Museum) until 1974.

The Explorer was restored and displayed at the Groton Navy Submarine base before it returned to its current location in Milford during the late 1990s.

Between 1960 and June 2010, Milford also had an elementary school that bore Simon Lake’s name. The school produced a newsletter named the Explorer.

Source: Simon Lake.com

Source: Simon Lake.com

Tags: Milford

The 1871 Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Providence’s Kennedy Plaza is notable for its size and details, as well as the tribute it paid to Rhode Island’s African American Civil War veterans.

The 1871 Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Providence’s Kennedy Plaza is notable for its size and details, as well as the tribute it paid to Rhode Island’s African American Civil War veterans.

The monument, directly in front of City Hall, stands in the plaza between where Fulton and Washington streets meet Dorrance Street.

The monument features a female allegorical with a laurel wreath in an outstretched right arm. A dedication on the monument’s front (northeast) face reads, “”Rhode Island pays tribute to the memory of the brave men who died that their country might live.”

A dedication plaque on the monument’s west base, erected by the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, honors the members of the 1st Rhode Island and the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) who fought in the Civil War.

The monument’s base includes four buttresses topped with bronze figures representing infantry, cavalry, artillery and naval veterans.

The monument’s base includes four buttresses topped with bronze figures representing infantry, cavalry, artillery and naval veterans.

Large bronze plaques on the monument’s base list residents killed in the war. The names are arranged by rank within their regimental affiliation.

Bronze bas-relief plaques also depict allegorical representations of war, victory, peace and history (illustrated as a African-American woman holding broken shackles).

The monument was designed by sculptor Randolph Rogers, who also created the Samuel Colt monument in Hartford, the Columbus Doors in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, and architect Alfred Stone. The figures were sculpted in Rome and cast in Munich, and the monument was assembled in Providence.

The monument was dedicated in its present location in 1871, and was moved in 1913 when Kennedy Plaza (then named Exchange Place) was constructed. It was returned to its original location in 1997 as part of renovations to the plaza.

The monument was dedicated in its present location in 1871, and was moved in 1913 when Kennedy Plaza (then named Exchange Place) was constructed. It was returned to its original location in 1997 as part of renovations to the plaza.

Tags: Rhode Island

Update: We’ve published Faith and Freedom: The National Monument to the Forefathers, a book describing this magnificent monument in more detail. Learn more.

A granite monument standing 81 feet tall honors the first English settlers to land in Plymouth, Mass.

A granite monument standing 81 feet tall honors the first English settlers to land in Plymouth, Mass.

The National Monument to the Forefathers stands in a state park on Allerton Street. If you look at the first picture in this post, the small people in the lower left will give you a good indication of the size of this massive and intricate monument.

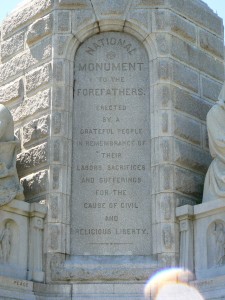

The monument, the largest solid-granite monument in the United States, was dedicated in 1889 (30 years after its cornerstone was laid).

A dedication on the monument’s northeast face reads, “National Monument to the Forefathers. Erected by a grateful people in remembrance of their labors, sacrifices and sufferings for the cause of civil and religious liberty.”

The monument features several allegorical figures depicting virtues the Pilgrims, known in Plymouth as the Forefathers, brought with them when they arrived in Massachusetts in 1620.

The monument features several allegorical figures depicting virtues the Pilgrims, known in Plymouth as the Forefathers, brought with them when they arrived in Massachusetts in 1620.

The largest figure, Faith, is 36 feet tall and weighs 180 tons by itself. Faith, holding a Bible, stands atop a granite column facing toward Plymouth Harbor and England. (The osprey nest on Faith’s head is not part of the original design.)

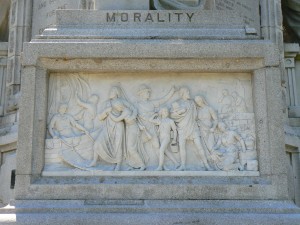

The eight-sided column features four buttresses with seated 15-foot-tall allegorical figures. Moving counterclockwise from the monument’s front, the north face features a representation of Morality, a woman holding a tablet bearing the beginning of the Ten Commandments, “I am the Lord thy God.”

Niches in the base of Morality’s throne honor prophecy and evangelism.

The west face depicts Law, a man holding a book. Law is flanked by smaller figures depicting justice and mercy.

Education graces the south face with a woman pointing to a book in her lap. Representations of wisdom and youth flank Education’s throne.

Education graces the south face with a woman pointing to a book in her lap. Representations of wisdom and youth flank Education’s throne.

The east face features a representation of Liberty, a seated warrior with a sword in his right arm and a broken chain in his left. He is flanked by depictions of peace and tyranny, symbolizing the defeat of tyranny and the resulting peace.

Along with the allegorical figures, the monument’s buttresses also feature bas-relief sculptures depicting scenes such as the Pilgrims departing England and landing on the shores of Plymouth and interacting with Native Americans.

The side of the monument’s face also bears panels listing the names of the Pilgrim settlers, and a quote from William Bradford, a governor of the colony.

The monument was designed primarily by Boston sculptor Hammatt Billings, who was also responsible for the Civil War monument in Concord, Mass. As large was the Forefathers monument stands, Billings’ original design called for it to be nearly twice as high at 150 feet (just under the Statue of Liberty’s height, including the pedestal, of 151 feet).

The monument’s height was reduced when funding became short during the Civil War.

The monument’s height was reduced when funding became short during the Civil War.

The monument was commissioned by the Pilgrim Society, which maintained the monument and the small park surrounding it until the site was deeded to the commonwealth in 2001.

The Pilgrims are also honored with a monument in Provincetown, Mass., that was dedicated in 1910. The Pilgrims originally landed in Provincetown, but after five weeks, decided the far end of Cape Cod would be better suited for T-shirt shops and restaurants than for farming. The group then migrated west to the more-sheltered area that became Plymouth.

Tags: Massachusetts

White Plains honors its Civil War veterans with a monument in a downtown park.

White Plains honors its Civil War veterans with a monument in a downtown park.

The Soldiers’ Monument, dedicated in 1872, features the uncommon choice of a zinc statue of an infantryman standing atop a more-traditional granite base. A dedication on the monument’s front (west) face reads, “To the soldiers of White Plains who died in the service of their country in the Civil War 1861-1865.”

The monument’s north and south faces each list the names of about a dozen residents killed in the conflict.

The east face bears the dedication, “Erected by their late comrades and the Town of White Plains, July 4, 1872.”

The monument stands in Tibbets Park, near the intersection of Main Street (Route 119) and South Broadway (Route 122).

The monument stands in Tibbets Park, near the intersection of Main Street (Route 119) and South Broadway (Route 122).

A large cherry tree directly in front of the monument prevents careful exploration and photography.

Information about the monument’s sculptor and supplier haven’t come to light, but the White Plains soldier is a copy of a monument that stood on the Civil War monument in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

White Plains’ World War I monument stands a short walk north of the Civil War monument. The monument, which features an artillery rifle, bears a simple dedication to soldiers, sailors and marines on its north face.

The use of zinc was relatively uncommon in Civil War monuments. Zinc was marketed as “white bronze” and used, primarily for smaller cemetery monuments, in the late 19th century. The material resists wearing and fading better than marble or granite, but can become brittle after extended exposure to cold weather.

In addition, large zinc monuments often have difficulty supporting their weight, so they often needed later reinforcement with internal steel frameworks.

In addition, large zinc monuments often have difficulty supporting their weight, so they often needed later reinforcement with internal steel frameworks.

All-zinc monuments can be found in Stratford, Conn., Gettysburg and several other locations.

The combination of zinc and granite found in White Plains can also be seen in Orleans, Mass.

Tags: New York

Stonington honors the successful defense of the town against British warships during the War of 1812 with a granite monument.

Stonington honors the successful defense of the town against British warships during the War of 1812 with a granite monument.

The 1830 obelisk, topped with a naval shell, stands in the borough of Stonington’s Cannon Square. An inscription on the monument’s north face reads, “These two guns of 18 pounds caliber were heroically used to repel the attack on Stonington of the English naval vessels Ramilies, 74 guns, Pactolus, 44, Dispatch, 20, Nimrod, 20 and the bomb ship Terror. August 10, 1814.”

The monument’s north face also contains the Latin inscription “In perpetuam rei memoriam” (In everlasting remembrance of the event).

The monument’s south face honors “the defenders of the fort,” and lists the names of 10 residents who presumably manned the cannons during the English attack.

The monument commemorates the defense of Stonington during a British naval bombardment that lasted between August 9-12, 1814. A group of five British warships anchored off Stonington and shelled the city. No lives were lost in the attack, but 40 local buildings were damaged.

The monument commemorates the defense of Stonington during a British naval bombardment that lasted between August 9-12, 1814. A group of five British warships anchored off Stonington and shelled the city. No lives were lost in the attack, but 40 local buildings were damaged.

The two cannons flanking the monument were returned to the monument site on Tuesday, August 3, after a two-year restoration at Texas A&M. The 18-pounder cannons, cast at West Point Foundry in the 1780s, will be rededicated in ceremonies Saturday.

Tags: Stonington

UPDATE (Sept. 2010) — The West Haven Historical Society has canceled efforts to sell the Campbell monument site. We’ve revised the post to remove references to a potential sale.

UPDATE (Sept. 2010) — The West Haven Historical Society has canceled efforts to sell the Campbell monument site. We’ve revised the post to remove references to a potential sale.

A monument in West Haven honors British adjutant who spared the life of a local minister during the American Revolution.

The William Campbell monument stands in a small park just north of the Boston Post Road, between Wade and Pruden Streets. The site is owned by the West Haven Historical Society.

The site today features an 1891 monument that, depending on which account you read, marks the approximate location of where William Campbell was killed during the British invasion of New Haven in 1779, or was buried after the battle.

The monument, a large granite block with a polished west face, bears a dedication reading, “Adjutant William Campbell fell during the British invasion of New Haven, July 5, 1779. Blessed are the merciful.”

The site is surrounded by a metal fence, and the monument is decorated with American and British flags.

The site is surrounded by a metal fence, and the monument is decorated with American and British flags.

During the invasion, Campbell (for whom Campbell Avenue is named) spared the life of a local minister who broke a leg while fleeing from British forces with documents. Campbell ordered troops not to kill the civilian, and Campbell was killed later that day.

According to Peter J. Malia’s excellent history of West Haven, Visible Saints, West Haven, Connecticut, 1648 – 1798 (affiliate link), Campbell’s burial site was unmarked until 1831, when a small headstone was placed on a location identified by a witness to the burial 52 years later. The headstone was later stolen by relic hunters and replaced with the 1891 memorial.

A sign at the monument site indicating the monument marks Campbell’s burial site is a bit optimistic, since the original grave has been lost to history. The site has been examined with ground penetrating radar, and no remains were found under the monument.

The site was maintained by the New Haven Colonial Society until 1977, when it was deeded to the West Haven Historical Society.

The site was maintained by the New Haven Colonial Society until 1977, when it was deeded to the West Haven Historical Society.

Tags: West Haven

A large monument marking the location of the county courthouse where New York proclaimed its independence stands in front of a former armory in White Plains, New York.

A large monument marking the location of the county courthouse where New York proclaimed its independence stands in front of a former armory in White Plains, New York.

The 1910 monument features a large bronze eagle atop granite blocks that served as part of the foundation of the first and second courthouse buildings to stand on the site.

A dedication on the monument’s east face reads, “Site of the county court house where on July 10, 1776, the provincial Congress proclaimed the passing of the dependent colony of New York and the birth of the independent state of New York.”

The monument, by sculptor Bruno Louis Zimm, was erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution in conjunction with the construction of a state armory on the site. The armory was converted into housing units and a senior center in the late 1980s.

The monument, by sculptor Bruno Louis Zimm, was erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution in conjunction with the construction of a state armory on the site. The armory was converted into housing units and a senior center in the late 1980s.

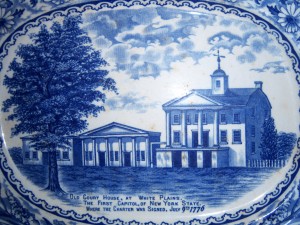

The courthouse site, on South Broadway (near the intersection of Mitchell Place), has long been an important landmark for White Plains. The first courthouse, depicted in a 1910 plate image posted by the White Plains Historical Society, was erected there in 1758.

In July of 1776, the charter creating New York State was signed at the courthouse after the state legislature was driven from New York City by British sympathizers. The Declaration of Independence was read at the site on July 11, 1776. In November of that year, the courthouse was burned by Continental forces following the Battle of White Plains.

The second courthouse was eventually replaced with a private mansion, and the site was turned over to the state for the armory. Stones that had been used in the foundations of both courthouses and the mansion today stand as part of the monument and a small plaza leading to it.

The second courthouse was eventually replaced with a private mansion, and the site was turned over to the state for the armory. Stones that had been used in the foundations of both courthouses and the mansion today stand as part of the monument and a small plaza leading to it.

Tags: New York

Prospect honors its war veterans with a monument in a small park just off Prospect Road (Route 68).

Prospect honors its war veterans with a monument in a small park just off Prospect Road (Route 68).

The Soldier’s Monument, completed in 1906 but dedicated the following year, features an infantryman standing atop a granite base decorated with bronze plaques and a Grand Army of the Republic medal.

A dedication plaque on the monument’s front (west) face reads, “To the loyal sons of Prospect who served in the wars of our country. The noblest motive is the public good.”

The base of the west face also features a small monument, dedicated in 1977, that honors the town’s veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

The monument’s south face has a plaque honoring the 25 Prospect residents who served in World War I. The undated plaque replaced a decorative trophy depicting two crossed rifles.

The monument’s south face has a plaque honoring the 25 Prospect residents who served in World War I. The undated plaque replaced a decorative trophy depicting two crossed rifles.

The east face has a plaque listing 22 names of residents who fought in the American Revolution and other wars, as well as Prospect’s 69 Civil War veterans.

The north face bears the emblem of the Grand Army of the Republic, the post-Civil War veterans’ organization.

Perhaps because of its relatively late construction in 1906, the Prospect monument features a number of design elements not commonly seen on other Civil War monuments in Connecticut. For instance, the infantryman’s rifle (a model 1861 Springfield musket) was fabricated from bronze. This use of a different material for the soldier and his rifle is unique in Connecticut.

Also unusual is the placement of the soldier’s left foot on a rock, as well as the uniform pants being tucked into his footwear. While the practice of tucking in pant legs to guard against ticks was not uncommon during the Civil War, this is the only time we’ve seen it depicted on a monument.

The monument was fabricated by the Thomas F. Jackson Co., which also supplied the Kenea Soldiers’ monument in Wolcott.

The monument was fabricated by the Thomas F. Jackson Co., which also supplied the Kenea Soldiers’ monument in Wolcott.

Not far from the Civil War monument, a small 1897 monument honors the location of the town’s original burying ground.

Bethany honors its veterans with a Wall of Honor in a local park as well as a monument outside Town Hall.

Bethany honors its veterans with a Wall of Honor in a local park as well as a monument outside Town Hall.

The Wall of Honor stands in a small plaza near the entrance to Veterans Memorial Park on Beacon Road (Route 42). The polished granite panels list 145 names of local veterans. The monument, which overlooks the park’s Hockanum Lake, also features bronze service emblems and stone benches that invite quiet reflection.

Outside Bethany Town Hall, a 1990 monument also honors local veterans. The monument bears a dedication reading, “To the memory of those citizens of Bethany who left home with the armed forces in defense of this nation.”

The Town Hall monument was carved by local sculptor Peter Horbick, a World War II veteran listed on the Wall of Honor. His other works include a monument to Quinnipiac Indians in New Haven’s Fort Wooster Park.