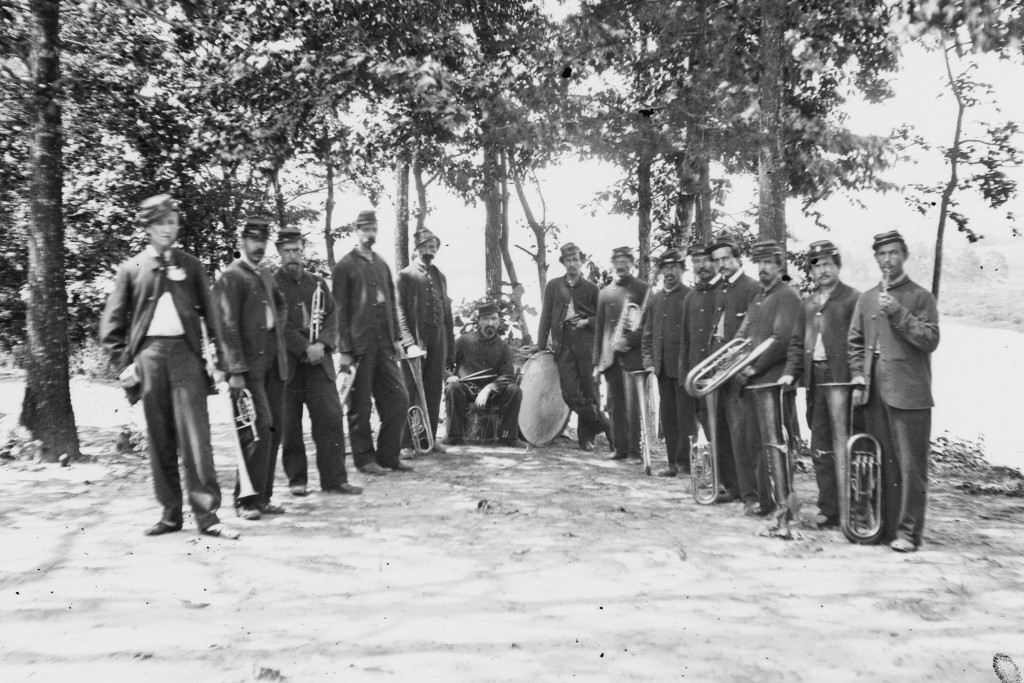

The First Connecticut Heavy Artillery band at Fort Darling, Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia, in April of 1965.

The full-resolution image is available at the Library of Congress.

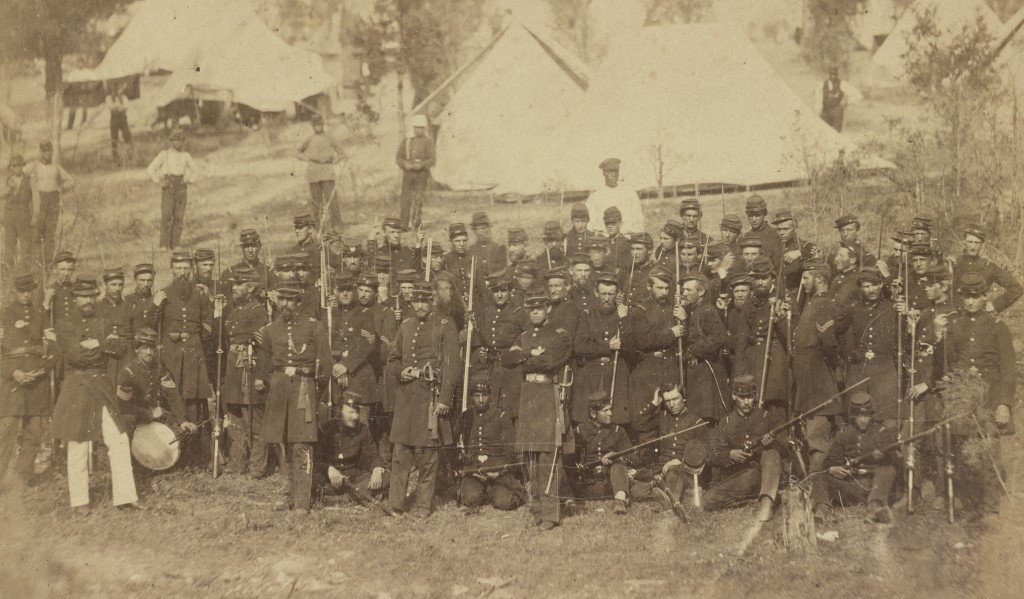

The 29th Regiment, comprised primarily of African American volunteers, is pictured in Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1864.

The regiment is also honored with monuments in New Haven and Danbury.

The original image is available at the Library of Congress.

Near Fredericksburg, Virginia, during the Battle of Chancellorsville.

The full image, in a variety of resolutions, can be viewed at the Library of Congress.

This undated image detail shows the First Regiment Connecticut Heavy Artillery, at Fort Richardson in Arlington, Virginia.

The First Heavy Artillery was formed in the spring of 1861 as the Fourth Volunteer Infantry. In January, 1862, the regiment was converted into a heavy artillery unit.

At Fort Richardson, the regiment participated in the defense of Washington, D.C.

When the Peninsula Campaign began in March of 1862, the First CT was deployed and participated in several engagements. The regiment returned to the defense of Washington and later was involved in fighting near Fort Fisher, N.C., as well as the sieges of Petersburg and Richmond.

The unit mustered out in September, 1865, after more than four years of service.

The full image, in a variety of resolutions, can be viewed at the Library of Congress.

In honor of Veterans’ Day, we’re going to run images of selected Connecticut Civil regiments from the Library of Congress this week.

Our first image (which you can click to enlarge) depicts the Third Connecticut Regiment Infantry, which served for three months at the beginning of the Civil War.

(Based on early (and overly optimistic) expectations that the Confederacy would be defeated quickly, members of early regiments enlisted for only 90 days.)

In a detail section from a larger image, one of the regiment’s companies is pictured during their training at Camp Douglass in Chicago. (The facility was initially used as a training ground, and became a Confederate prison camp in 1862.)

The regiment left Hartford in May of 1861, and participated in the first Battle of Bull Run in July. The unit mustered out in Hartford in mid-August.

Among the regiment’s officers was Douglas Fowler, a Guilford native and Norwalk locksmith who would later re-enlist in the 8th volunteer infantry regiment, and muster out in February 1862, and then he joined the 17th volunteer infantry regiment. Fowler was commanding the 17th when he was killed in Gettysburg during the battle’s first day.

The full image, in a variety of resolutions, can be viewed at the Library of Congress site.

Connecticut honors American Revolution hero Thomas Knowlton with a statue on the grounds of the state capitol.

Connecticut honors American Revolution hero Thomas Knowlton with a statue on the grounds of the state capitol.

The statue, near the corner of Trinity Street and Capitol Avenue, honors Knowlton, a Massachusetts native whose family moved to Ashford, Connecticut, when he was a child.

At the age of 15, Knowlton fought in the French and Indian War. During the Revolution, he led Connecticut troops during the Battle of Bunker Hill and was killed during the Battle of Harlem Heights.

At the age of 15, Knowlton fought in the French and Indian War. During the Revolution, he led Connecticut troops during the Battle of Bunker Hill and was killed during the Battle of Harlem Heights.

Knowlton led a group of scouts that gathered valuable intelligence before the battle. His troops included Nathan Hale, who was captured and executed by British forces after volunteering to serve as a spy.

The statue, dedicated in 1895, depicts Knowlton with a drawn sword. A dedication on the east side of the monument’s base reads, “In memory of Colonel Thomas Knowlton of Ashford Conn. who as a boy served in several campaigns in the French and Indian Wars, shared in the siege and capture of Havana in 1762, was in immediate command of Connecticut troops at the Battle of Bunker Hill, was with his commands closely attached to the person of Washington, and was killed at the Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16, 1776, at the age of thirty-six.”

The statue, dedicated in 1895, depicts Knowlton with a drawn sword. A dedication on the east side of the monument’s base reads, “In memory of Colonel Thomas Knowlton of Ashford Conn. who as a boy served in several campaigns in the French and Indian Wars, shared in the siege and capture of Havana in 1762, was in immediate command of Connecticut troops at the Battle of Bunker Hill, was with his commands closely attached to the person of Washington, and was killed at the Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16, 1776, at the age of thirty-six.”

The statue was created by Enoch Smith Woods, whose other works include a Hale statue at the Wadsworth Atheneum, a bust of Hale in East Haddam, and a Hartford plaque honoring anesthesia pioneer Horace Wells.

The statue was created by Enoch Smith Woods, whose other works include a Hale statue at the Wadsworth Atheneum, a bust of Hale in East Haddam, and a Hartford plaque honoring anesthesia pioneer Horace Wells.

Tags: Hartford

A French nobleman who played key roles in supporting the Continental Army during the American Revolution is honored with a statue in Hartford.

A French nobleman who played key roles in supporting the Continental Army during the American Revolution is honored with a statue in Hartford.

The Marquis de Lafayette memorial, at the corner of Capitol Avenue and Lafayette Street, stands on a traffic island across from the State Capitol building.

The statue, dedicated in 1932, depicts Lafayette, on horseback with an uplifted sword, leading troops into battle.

The statue, dedicated in 1932, depicts Lafayette, on horseback with an uplifted sword, leading troops into battle.

A plaque added to the east side of the monument’s base in 1957 bears Lafayette’s birth and death dates, and an inscription describing him as “A true friend of liberty, who served as a major general in the Continental Army with ‘all possible zeal, without any special pay or allowances’ until the American colonists secured their freedom, and whose frequent visits to this state as aide to Washington as liaison officer with supporting French troops, and in the pursuit of freedom, are gratefully remembered.”

Lafayette came to America as a 19-year-old in late 1776, and served alongside Washington. During the war, he returned to France and helped secure that nation’s military and political support of the revolution.

Lafayette came to America as a 19-year-old in late 1776, and served alongside Washington. During the war, he returned to France and helped secure that nation’s military and political support of the revolution.

Lafayette was imprisoned during the French Revolution, and after his release, returned to the United States in 1824-25 for a 24-state tour that included stops in New Haven, Tolland and Middletown, CT. During the tour, Lafayette laid the cornerstone for the Bunker Hill monument in Massachusetts.

The statue, by sculptor Paul Wayland Bartlett, is a copy of a 1907 statue in Paris. The statue originally stood across Capitol Avenue, but was moved in 1979 to improve traffic patterns in the area. (The postcard image at the bottom of this post shows the statue in its original location.)

The statue, by sculptor Paul Wayland Bartlett, is a copy of a 1907 statue in Paris. The statue originally stood across Capitol Avenue, but was moved in 1979 to improve traffic patterns in the area. (The postcard image at the bottom of this post shows the statue in its original location.)

A small turtle stands near the horse’s left hoof. Various theories suggest the turtle may be a coded complaint about the pace of payment to Bartlett, or a secret apology for the pace of the statue’s completion.

Tags: Hartford

Hartford honors the victims of the city’s worst disaster with a memorial on the site of the 1944 circus fire.

Hartford honors the victims of the city’s worst disaster with a memorial on the site of the 1944 circus fire.

On July 6, 1944, a fire during a performance of the Ringling Bros., Barnum & Bailey Circus claimed an estimated 168 lives and caused hundreds of injuries.

Those lost and injured during the tragedy are honored with a memorial dedicated in 2005 in a park behind the Fred D. Wish elementary school on Barbour Street.

Those lost and injured during the tragedy are honored with a memorial dedicated in 2005 in a park behind the Fred D. Wish elementary school on Barbour Street.

A memorial ring marking the center of the circus tent lists the names and ages of the victims, the majority of which were children and women.

Near the center ring, memorial bricks bear messages from family members and survivors. Dogwood trees at the site mark the edges of the circus tent.

Near the center ring, memorial bricks bear messages from family members and survivors. Dogwood trees at the site mark the edges of the circus tent.

A pathway from the northern end of the park is lined with granite pedestals with plaques providing information about the tragedy.

The tranquility of the site on a Sunday morning belie the chaos and tragedy on the afternoon of the fire, which broke out about 20 minutes into the performance. A small fire spread rapidly, aided by paraffin and gasoline used as a waterproof coating on the circus tent. The tent collapsed

The tranquility of the site on a Sunday morning belie the chaos and tragedy on the afternoon of the fire, which broke out about 20 minutes into the performance. A small fire spread rapidly, aided by paraffin and gasoline used as a waterproof coating on the circus tent. The tent collapsed

In addition to the flames, people died after being crushed in the stampede out of the tent, or from injuries sustained after jumping from the bleachers.

The cause of the fire was never established.

The cause of the fire was never established.

Tags: Hartford

A monument to Abraham Lincoln in Hingham, Mass., honors an ancestral connection between the president and the town.

A monument to Abraham Lincoln in Hingham, Mass., honors an ancestral connection between the president and the town.

Lincoln’s early relatives, including his great-great-great-great grandfather Samuel, were among the English settlers of Hingham.

The Lincoln statue, on a green near Samuel Lincoln’s home on Lincoln Street, was dedicated in 1939. The south face of the monument’s base bears an inscription with the “With malice toward none, with charity for all” excerpt from Lincoln’s second inaugural address in 1865.

The Lincoln statue, on a green near Samuel Lincoln’s home on Lincoln Street, was dedicated in 1939. The south face of the monument’s base bears an inscription with the “With malice toward none, with charity for all” excerpt from Lincoln’s second inaugural address in 1865.

The north face bears a dedication to the family of Everett Whitney, a local lumber dealer who funded with statue with a $30,000 donation (more than $492,000 in today’s dollars) bequest.

The sculpture was created by Charles Keck, whose other works include a Harry S. Truman bust in the U.S. Capitol, the Father Francis P. Duffy statue in New York’s Time Square, the bronze USS Maine plaque that was mounted in nearly 1,000 locations and numerous other works.

The sculpture was created by Charles Keck, whose other works include a Harry S. Truman bust in the U.S. Capitol, the Father Francis P. Duffy statue in New York’s Time Square, the bronze USS Maine plaque that was mounted in nearly 1,000 locations and numerous other works.

A memorial near the north end of the green honors Benjamin Lincoln, another descendent of Hingham’s settlers. Benjamin Lincoln served as a major general during the American Revolution, and accepted the British surrender at Yorktown. He also served as the first secretary of war of the United States.

Tags: Massachusetts

Rhode island founder Roger Williams is honored with a monument in, fittingly enough, Providence’s Roger Williams Park.

Rhode island founder Roger Williams is honored with a monument in, fittingly enough, Providence’s Roger Williams Park.

The monument, dedicated in 1877, depicts a standing Williams holding a book inscribed with the words “soul” and “liberty”.

At the monument’s base, Clio (the muse of history) is inscribing Williams’ name and 1636, the year of Providence’s founding.

The Clio figure originally held a metal quill in her right hand, and the monument once featured a bronze shield, scroll and wreath near Clio’s feet (the missing elements can be seen in the 1905 black-and-white image from the Library of Congress).

The Clio figure originally held a metal quill in her right hand, and the monument once featured a bronze shield, scroll and wreath near Clio’s feet (the missing elements can be seen in the 1905 black-and-white image from the Library of Congress).

The land for Roger Williams Park, and funding for the statue, were donated to the city by Williams’ great-great-great granddaughter Betsy. The park site was part of Williams’ land grant from the Narragansett tribe and the location of the family farm.

The monument was sculpted by Franklin Simmons, whose other works include the U.S. Grant memorial at the U.S. Capitol. Another version of the statue, without the Clio figure, is displayed in the Capitol building.

The monument was sculpted by Franklin Simmons, whose other works include the U.S. Grant memorial at the U.S. Capitol. Another version of the statue, without the Clio figure, is displayed in the Capitol building.

Not far from the Williams monument, a bronze bust and bench honor Richard H. Deming, a former president of the Providence park commission. The bust was dedicated in 1904.

Tags: Rhode Island