A battlefield cross and a large granite monument in the Centerbrook section of Essex honor local veterans.

A battlefield cross and a large granite monument in the Centerbrook section of Essex honor local veterans.

The Essex Veterans Memorial, located near the intersections of Main Street, Deep River Road and Westbrook Road, features a granite wall we’re estimating to be seven or eight feet high. The west face of the monument honors veterans of World War I and World War II, listing the names of about 180 World War I veterans (including 10 who were killed in the war). The World War II listing, which continues on the east face, lists about 216 names and highlights 8 who were killed.

The east face also honors local veterans who served in Korea and Vietnam, with the Korea section listing about 130 names and the Vietnam section listing about 250. Both sections honor one local hero killed in the respective wars.

Near the granite wall is a battlefield cross memorial encased in a vented plastic box. The battlefield cross, following a military tradition believed to have started in the Civil War, features an inverted rifle, a helmet, dog tags, goggles, a pair of boots and several other personal items.

A granite marker near the battlefield cross display reads “Yesterday, today and forever, we honor those who served our country in the cause of liberty. Dedicated November 11, 1987. Essex Veterans Memorial.”

A granite marker near the battlefield cross display reads “Yesterday, today and forever, we honor those who served our country in the cause of liberty. Dedicated November 11, 1987. Essex Veterans Memorial.”

Battlefield cross memorials are typically created to honor fallen comrades in the field or at military bases. We’re not aware of similar outdoor memorials in Connecticut, and were impressed by the simplicity and power of the Essex memorial.

Thanks to the reader who told us about this memorial.

Tags: Centerbrook, Essex

Old Saybrook honors its Civil War veterans with a simple monument in Riverside Cemetery.

Old Saybrook honors its Civil War veterans with a simple monument in Riverside Cemetery.

The undated monument stands in a small traffic island near the cemetery’s main entrance from Sheffield Street. A dedication on its front (south) face reads “In memory of our comrades who served in the war of the rebellion. Erected by the veterans of Old Saybrook.”

At the base of the monument are the years in which the Civil War took place, 1861-1865.

The monument is not dated, but the reference to the “war of the rebellion,” likely indicates the monument was erected in the late 19th Century. By the early 20th Century, the conflict was more commonly described as the Civil War.

The monument has no lettering on its other faces. A smaller, more modern granite marker at the base of the monument bears the inscription “Veterans’ Memorial.” Several Civil War veterans are buried in the sections near the monument.

A short distance southwest of the cemetery, three monuments in front of Town Hall honor the veterans of the 20th Century’s Wars. A 1926 boulder monument honoring the service of World War I veterans bears a dedication on its front (west) face reading “In memory of Old Saybrook’s sons who served. The east face of the monument has a plaque with two columns of names listing local veterans, organized by service branches. The monument is topped by a bronze eagle.

Near the World War monument, a granite monument dedicated in 1961 honors local war heroes. A dedication near the top of the monument reads, “Erected by the citizens of Old Saybrook in memory of her sons who died at war.”

Near the World War monument, a granite monument dedicated in 1961 honors local war heroes. A dedication near the top of the monument reads, “Erected by the citizens of Old Saybrook in memory of her sons who died at war.”

Beneath that dedication, the monument lists heroes and the wars in which they were lost. One person is listed for World War I; 15 for World War II; two for Korea, and one for Vietnam.

A polished granite monument in front of three flagpoles bears the POW-MIA logo. An eternal flame flickers in front of the POW-MIA monument.

Bethel honors its World War I veterans with a local version of a notable Doughboy statue.

Bethel honors its World War I veterans with a local version of a notable Doughboy statue.

The monument features one of two copies of a statue by sculptor E.M. Viquesney known formally as the “Spirit of the American Doughboy.” At least 138 other versions of this statue are displayed in the United States, including a monument in North Canaan and three versions in New York state. (We visited the North Canaan monument in July and the Harrison, N.Y. monument in September.)

The dedication on the front (south) side of the monument’s base reads, “Erected by the Community Association of Bethel in honor of her war veterans.” The base also bears the monument’s 1928 dedication date.

Like most copies of the Doughboy statue, Bethel’s monument has been repaired a number of times over the years. The bayonet is a copy modeled after the North Canaan monument.

Unlike the copies in North Canaan and Harrison, Bethel’s Doughboy has the original barbed wire between the two tree stumps near the soldier’s feet.

Bethel’s monument is located in Doughboy Square, on a triangular green in the heart of downtown. (The gentleman in the background is preparing a holiday display on the green.) The area around the green was originally named for Bethel native P.T. Barnum, and was renamed in 2004. Barnum had donated a large bronze fountain in the square that had deteriorated by the mid-1920s and was replaced by the Doughboy monument.

Bethel’s monument is located in Doughboy Square, on a triangular green in the heart of downtown. (The gentleman in the background is preparing a holiday display on the green.) The area around the green was originally named for Bethel native P.T. Barnum, and was renamed in 2004. Barnum had donated a large bronze fountain in the square that had deteriorated by the mid-1920s and was replaced by the Doughboy monument.

Source: Spirit of the American Doughboy Database

Tags: Bethel

Bethel honors 14 Civil War heroes with a granite monument at the top of a hill in Center Cemetery.

Bethel honors 14 Civil War heroes with a granite monument at the top of a hill in Center Cemetery.

The monument, dedicated in 1892, was carved from a 14-foot block of solid granite and features distinctive carvings. A dedication on the front (north) face reads, “In memory of the soldiers and sailors of Bethel who gave their lives in defence of the Union 1861-1865.”

The dedication’s carving resembles a scroll suspended from a rod that hangs from just below the feet of an eagle near the top of the monument’s face. A ribbon unfurled next to the eagle reads “Union,” and “Liberty.”

The monument’s base features an intricately carved trophy featuring two rifles and crossed swords along with a soldier’s equipment belt, hat, rucksack and bedroll.

The monument’s south face lists the names and regimental affiliations of 14 residents who were killed in the war.

The monument’s south face lists the names and regimental affiliations of 14 residents who were killed in the war.

The sides of the monument are mostly rough rock face, other than two granite cannonball pyramids.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: Bethel

A tall monument topped by an allegorical standard-bearer honors Newtown’s soldiers and sailors.

A tall monument topped by an allegorical standard-bearer honors Newtown’s soldiers and sailors.

The monument features three pillars rising from a base dominated by benches. A dedication on the west face of the monument’s base reads, “Newtown remembers with grateful prayers and solemn vows her sacred dead [and] her honored living who ventured all unto death that we might live a republic with independence, a nation with union forever, a world with righteousness and peace for all.”

The monument is surrounded by a series of Honor Roll plaques listing local residents who have served in the nation’s wars. The front of the monument features a plaque honoring veterans of the Civil War and the World War, and another plaque lists veterans of the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Mexican War (in the 1840s), the Spanish-American War, and the Mexican Border War (in 1915-16).

Moving counter-clockwise around the base of the monument, plaques list veterans of the Persian Gulf War (1990-91); Vietnam; Korea; and World War II.

The helmeted allegorical figure atop the monument, representing Peace, stands with a flag, a laurel branch and a chain tucked in her arms.

The helmeted allegorical figure atop the monument, representing Peace, stands with a flag, a laurel branch and a chain tucked in her arms.

The monument was designed by Franklin L. Naylor, who was also responsible for a war memorial in Jersey City, N.J.

The monument was erected in 1931 on the site of a former schoolhouse that was later moved and turned into a private home. The monument’s formal dedication took place in 1939.

The monument is more commonly known as the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, but according to the Newtown Historical Society, the artist’s original blueprints list the name as the Liberty and Peace Monument. The society’s newsletter advocated a return to the original name, so we’re doing our small part in promoting the change.

Sources: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: Newtown

A doughboy statue in the southeast corner of New York City’s DeWitt Clinton Park honors residents of the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood lost in World War I.

A doughboy statue in the southeast corner of New York City’s DeWitt Clinton Park honors residents of the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood lost in World War I.

A dedication on the front (south) side of the monument’s base features the conclusion of John McCrae’s poem “In Flanders Fields.” The excerpt reads, “If ye break faith with us who die, We shall not sleep, though poppies grow, In Flanders fields.”

The soldier stands facing south, with poppy flowers in his right hand and a rifle slung over his left shoulder. We’re assuming flowers were attached to his right wrist with a rubber band to honor Veterans’ Day, which took place a week before we visited the park.

A dedication on the north face of the monument’s base reads, “Dedicated on Memorial Day 1930 by comrades and friends under the auspices of the Clinton District Monument Association as a memorial to the young folk of this neighborhood who gave their all in the World War.”

The 1930 dedication date on the monument’s base conflicts with New York’s Parks Dept., which lists the monument being dedicated on Veterans’ Day in 1929.

Either way, the statue was created by sculptor Burt W. Johnson, who was also responsible for a number of public works, including a doughboy statue displayed in a park in Queens.

Either way, the statue was created by sculptor Burt W. Johnson, who was also responsible for a number of public works, including a doughboy statue displayed in a park in Queens.

DeWitt Clinton Park, which runs between 52 and 54 streets and between 11 and 12 avenues, was created in 1905 when the city acquired a portion of Clinton’s former farm. DeWitt Clinton was a former U.S. senator, mayor of New York City and governor of the state who was largely responsible for New York City’s grid-based street pattern, and for advocating the construction of the Erie Canal.

A number of cities and counties have been named for Clinton, as was Castle Clinton, a fort at the southern end of Manhattan that’s now a National Park Service site (and hosts the ticket offices for the Statue of Liberty ferries).

The neighborhood around the park is known as Hell’s Kitchen and as Clinton (a more genteel name being promoted by community advocates and real estate interests).

Source: New York City Department of Parks & Recreation

Madison honors its war veterans with an 1897 memorial hall on the outskirts of the town green.

Madison honors its war veterans with an 1897 memorial hall on the outskirts of the town green.

Marble plaques mounted near the main (southwest) entrance to the building list the names, rank and regimental affiliation of “Madison volunteers in the war for the Union 1861-1865.” The plaques both have about 68 names each.

Immediately alongside the entrance, similar marble plaques list residents who served in the First World War. An honor roll inside the building lists the names and dates of death of four residents who died in the American Revolution; 41 who were killed in the Civil War; seven who were killed in World War I; nine in World War II; three in Korea; and three in Vietnam.

The high total for the Civil War reflects in part the concentration of Madison residents in the 14th Regiment of the Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, which saw its first action at the Battle of Antietam less than three months after its formation in May of 1862. Of the 41 residents killed in the Civil War, a dozen died between Antietam (September 17) and the end of 1862.

The high total for the Civil War reflects in part the concentration of Madison residents in the 14th Regiment of the Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, which saw its first action at the Battle of Antietam less than three months after its formation in May of 1862. Of the 41 residents killed in the Civil War, a dozen died between Antietam (September 17) and the end of 1862.

Memorial Town Hall, as the building is known today, was built to honor the town’s Civil War veterans. Like several communities in the state, Madison was divided on the idea of building a now-traditional Civil War monument or using the money for a more-practical civic building.

In the end, Madison got both because Vincent Meigs Wilcox a wealthy merchant who had donated to the Memorial hall fundraising efforts, also sponsored the construction of the Wilcox Soldiers’ Monument. That monument, which we highlighted in a September post, is located about three-quarters of a mile to the west in Madison’s West Cemetery.

Memorial Hall served as a community and recreation center until 1938, when it was converted into Madison’s Town Hall. In 1995, when the current town hall was built, the hall was renovated again and today hosts several municipal offices and meeting rooms, as well as the Charlotte L. Evarts Memorial Archives.

As you can see from the 1905 postcard image near the bottom of this post, the building once displayed Civil War mortars near the entrance. The mortars were donated to a World War II scrap drive.

As you can see from the 1905 postcard image near the bottom of this post, the building once displayed Civil War mortars near the entrance. The mortars were donated to a World War II scrap drive.

The large banner on the southern side of the building honors the 335 residents who served in World War II (denoted by the blue star) and the nine who were lost in the conflict (honored by the gold star).

A bust outside the hall honors James Madison, the fourth president of the United States. A series of nearby monuments honor the service of local veterans in the American Revolution, World War I, and World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

Sources: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Charlotte L. Evarts Memorial Archives

A large cannon honoring Civil War and American Revolution veterans is one of several war memorials on the East Haven green.

A large cannon honoring Civil War and American Revolution veterans is one of several war memorials on the East Haven green.

The cannon, a Civil War Rodman Gun, was dedicated in 1911. A plaque on the western face of its base reads, “This tribute to the worth of her sons, who have by land and sea offered their lives in defense of their country, is erected by the citizens of East Haven.”

The western face of the cannon also features a plaque, dedicated in 2002, listing the names of 16 residents who died in the American Revolution.

The eastern face has a similar plaque listing 15 men killed during the Civil War, including two who died in the Confederate prisoner of war camp in Andersonville, Georgia.

The cannon was one of three originally installed at Fort Nathan Hale in New Haven near the end of the Civil War. During the Spanish-American War, the cannons were moved to Lighthouse Point to help protect New Haven harbor.

The cannon was one of three originally installed at Fort Nathan Hale in New Haven near the end of the Civil War. During the Spanish-American War, the cannons were moved to Lighthouse Point to help protect New Haven harbor.

After the Spanish-American War, the cannons were donated to East Haven, North Haven and Milford for use as war memorials. The East Haven and North Haven cannon survive, but the Milford Rodman Gun was donated to a World War II scrap metal drive.

The cannon is one of several monuments on East Haven’s green. The northwest corner features a 1988 granite pillar, topped with a globe, that is dedicated to all of East Haven’s veterans.

Heroes lost in the two World Wars are listed on plaques mounted on pinkish monuments. The World War I plaque lists five names, while the World War II plaque lists 24 names.

Heroes lost in the two World Wars are listed on plaques mounted on pinkish monuments. The World War I plaque lists five names, while the World War II plaque lists 24 names.

A monument in the southwest corner of the green honors the service of local firefighters.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: East Haven

On Veterans’ Day, the city of Bridgeport dedicated a monument to its Korean War heroes.

On Veterans’ Day, the city of Bridgeport dedicated a monument to its Korean War heroes.

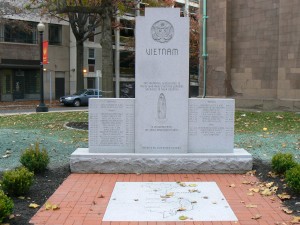

The new monument joins the World War II memorial dedicated in June, the 1932 World War memorial and the 1983 Vietnam memorial at the western end of McLevy Hall, a former City Hall building that hosted an 1860 speech by Abraham Lincoln.

The monument, built to your right as you face the World War II memorial, lists the names of 29 city residents lost in the Korean conflict. It also includes a quote from Harry S. Truman describing the war as well as two Bible verses. A map of Korea stands in front of the monument.

We were unfortunately unable to attend the dedication ceremony, but according to Connecticut Post coverage, nearly 200 veterans and family members were thanked for their service.

The plaza containing the war memorials, named after Bridgeport resident Col. Henry Mucci (who organized a rescue operation of Bataan Death March survivors) has changed this year to accommodate the new monuments. (Col. Mucci has also been honored with a local highway, but the plaza is probably a more dignified tribute.)

The plaza containing the war memorials, named after Bridgeport resident Col. Henry Mucci (who organized a rescue operation of Bataan Death March survivors) has changed this year to accommodate the new monuments. (Col. Mucci has also been honored with a local highway, but the plaza is probably a more dignified tribute.)

As you can see in images from previous visits, the Vietnam memorial that stood in the center the plaza has been moved to the left of the World War II memorial, and a memorial brick walkway has been added.

Congratulations to local veterans for this well-deserved honor, and to city officials for their efforts in recognizing the contributions and sacrifices made by local heroes.

An 1867 marble statue depicting a Civil War cavalry officer being greeted by a young girl stands outside Connecticut’s home for veterans in Rocky Hill.

An 1867 marble statue depicting a Civil War cavalry officer being greeted by a young girl stands outside Connecticut’s home for veterans in Rocky Hill.

The statue was originally located in Darien at the state’s first veterans’ facility, Fitch’s Home for Soldiers and Orphans. That facility was founded by Benjamin Fitch, a wealthy dry goods merchant, who helped raise a regiment and promised its members he would care for wounded veterans and their orphaned children.

Fitch’s home became a state facility, and the population ebbed and flowed between the Civil War and the World War I before peaking at more than 1,000 soldiers during the Great Depression.

Recognizing the need for a bigger facility, the state opened the Rocky Hill home for veterans. The vets who moved to Rocky Hill included a 97-year-old Civil War veteran.

In 1950, the Returned Soldier statue was moved from the former Fitch Home site to Spring Grove Cemetery, the site of a memorial flagpole we visited in March. More than 2,100 vets are buried at Spring Grove, the first veterans’ cemetery in the state.

In 1950, the Returned Soldier statue was moved from the former Fitch Home site to Spring Grove Cemetery, the site of a memorial flagpole we visited in March. More than 2,100 vets are buried at Spring Grove, the first veterans’ cemetery in the state.

In 1985, the statue was moved to Rocky Hill, restored and placed on its granite base.

The statue was sculpted by Larkin Goldsmith Mead, a New Hampshire native who moved to Italy. Some of his other public works include the statues on Abraham Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Ill.

On Veterans Day, we thank the men and women (and their families) who have served our country.

Sources: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

History of Connecticut Veterans’ Home

Tags: Rocky Hill