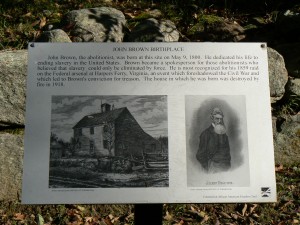

On the 150th anniversary of abolitionist John Brown’s raid on a Federal armory in Harpers Ferry, we’re taking a look at the Torrington site of his birthplace.

On the 150th anniversary of abolitionist John Brown’s raid on a Federal armory in Harpers Ferry, we’re taking a look at the Torrington site of his birthplace.

Brown was born in 1800 on what is now John Brown Road. The site, listed on Connecticut’s Freedom Trail, today consists of a small roadside clearing surrounded by a stone wall. A boulder, erected in 1932, has an inscription on its south side reading, “In a house on this site, John Brown was born May 9, 1800.”

The site also has a wayside marker explaining the homestead was destroyed in a fire in 1918. Within the clearing, there are few signs of the former house, other than a large boulder at the eastern end of the property with a round hole that appears to have been part of a well or cistern.

The Brown family moved to Ohio in 1805. Brown moved to Massachusetts in 1816 before returning to Litchfield to study to become a minister. Eye inflammation and a lack of money prompted his return to Ohio.

The Brown family moved to Ohio in 1805. Brown moved to Massachusetts in 1816 before returning to Litchfield to study to become a minister. Eye inflammation and a lack of money prompted his return to Ohio.

In 1856, Brown and his followers killed five pro-slavery Southerners, one of several violent incidents that year in Kansas as supporters and opponents debated whether slavery would be allowed there.

During the Harpers Ferry attack in 1859, Brown led an army of followers who tried to seize the Federal armory in hopes of using the weapons to instigate a slave rebellion. Most of the attackers were killed or captured, and Brown was eventually surrounded in the armory’s engine house. After a standoff, U.S. troops led by Robert E. Lee stormed the engine house and captured Brown, who was convicted of treason and hanged on December 2, 1859. He was buried in North Elba, N.Y.

Brown’s raid, trial and execution helped further inflame the slavery debate that would lead to the Civil War. Less than a year later, South Carolina would become the first state to secede from the United States, and the first battle would take place 14 months later.

Brown’s raid, trial and execution helped further inflame the slavery debate that would lead to the Civil War. Less than a year later, South Carolina would become the first state to secede from the United States, and the first battle would take place 14 months later.

The images of Harpers Ferry are from a visit in 2005. After John Brown’s raid, the engine house became a tourist attraction, and was displayed at a Chicago fair in the 1890s. The building was returned to Harper’s Ferry and displayed on a local farm, and then a college campus. In 1968, the National Park Service returned the building to a site near its original location, which had been covered by a railroad embankment.

A granite monument marks the actual location of the engine house during Brown’s raid.

Sources: Torrington Historical Society

National Park Service: Harpers Ferry

A 1904 granite monument in Seymour’s French Memorial Park honors the town’s Civil War heroes.

A 1904 granite monument in Seymour’s French Memorial Park honors the town’s Civil War heroes.

The Soldiers’ Monument, whose design is based on a monument dating back to ancient Athens, features a granite infantry soldier standing atop a domed shaft supported by six pillars.

A dedication on the front (south) face reads, “This monument is erected by the citizens of Seymour in honored memory of the defenders of our country 1861-1865.” Above the open area created by the column, a band lists the battles of Gettysburg, James Island (near Charleston, S.C.), Atlanta and Antietam.

The vintage postcard near the bottom of this post, mailed in October of 1906 to Howard Avenue in Bridgeport, illustrates how the monument has changed over the years. The round fence, for instance, was added later. The monument also featured a tripod formed by three rifles in the area enclosed by the pillars. The rifles belong to the Seymour Historical Society after being stolen and recovered.

Also, a cannonball pyramid has been removed since the Connecticut Historical Society surveyed the monument in 1993.

Also, a cannonball pyramid has been removed since the Connecticut Historical Society surveyed the monument in 1993.

The monument also has three 30-pounder Parrott rifles at the base, similar to those found at nearby Civil War monuments in Derby and Ansonia. The markings on the Seymour cannon are difficult to discern, but at least one was forged in 1864 by the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, N.Y.

A collection of other war monument stands to the east of the Soldiers’ Monument. Residents who served in the two World Wars are honored by a large monument with four plaques (three of which are dedicated to World War II). The World War I plaque lists four columns of residents who served in the conflict, and honors 13 residents who were killed. Each of the three World War II plaques has four columns of names and collectively honor 31 residents who were killed.

A Vietnam monument has four columns of names and honors two residents who were killed. A Korean War monument has three columns and also honors two residents who were killed. A Revolutionary War monument has two columns of names.

A Vietnam monument has four columns of names and honors two residents who were killed. A Korean War monument has three columns and also honors two residents who were killed. A Revolutionary War monument has two columns of names.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

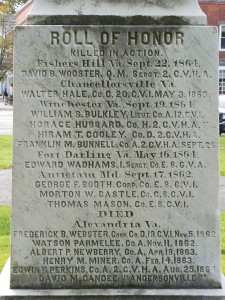

Litchfield honors its Civil War heroes with a marble obelisk on the green.

Litchfield honors its Civil War heroes with a marble obelisk on the green.

A dedication on the front (south) face of the monument, which was dedicated in 1874, reads, “Pro Patria” (“For one’s country in Latin). The dedication is the centerpiece of an artistic bas relief featuring two weeping soldiers, draped flags, crossed rifles and cannonballs.

The south shaft also features an intricate state of Connecticut seal (the ribbon with the state motto extends beyond the shaft’s edges), four flags and a cross that may symbolize the Army of the Potomac’s Sixth Corps (which used a squared-off cross as its emblem). The south shaft also lists the battles of Fisher’s Hill and Fort Darling, both in Virginia.

The east face contains the names, regimental affiliation, and the date and place of death of 20 residents lost in the conflict, and lists the battles of Antietam (Md.) and Fort Harrison (Va.)

The north face honors 17 residents killed in the war, and lists the battles of Petersburg and North Anna, both in Virginia.

The north face honors 17 residents killed in the war, and lists the battles of Petersburg and North Anna, both in Virginia.

The west face lists 19 residents, as well as the battles of Winchester and Cold Harbor, both in Virginia.

East of the monument, across South Street, is a boulder with a 1908 plaque honoring the former location of a church in which Lyman Beecher, father of Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe, preached.

To the southwest is a group of three granite memorials with bronze plaques honoring the veterans of Korea, World War II and Vietnam. The Korea monument has four columns listing residents who served. The World War II monument has plaques on its front and rear, both with four columns, that list a total of 17 residents who were lost in the conflict. The Vietnam memorial has four columns of residents who served, and honors one who was killed.

Near these monuments is the town’s World War monument, which lists four columns of residents who served, and indicates nine were killed.

A marker south of the Pro Patria monument indicates the site of a recruiting tent for the 19th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. The unit was formed in Litchfield, and deployed to Washington, D.C., in September of 1862 to serve in the garrison defending the capital. In November of 1863, the regiment shifted from the infantry to the artillery, and became the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery. The unit participated in the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor and various 1865 engagements around Petersburg, Va. Of the 2,719 men who served in the unit, 409 were killed, injured or died from disease.

A marker south of the Pro Patria monument indicates the site of a recruiting tent for the 19th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. The unit was formed in Litchfield, and deployed to Washington, D.C., in September of 1862 to serve in the garrison defending the capital. In November of 1863, the regiment shifted from the infantry to the artillery, and became the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery. The unit participated in the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor and various 1865 engagements around Petersburg, Va. Of the 2,719 men who served in the unit, 409 were killed, injured or died from disease.

The cannon west of the Pro Patria monument was cast in 1845 by the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, N.Y.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: cannon, Litchfield

Congratulations to volunteers from the Connecticut Nursery & Landscape Association, Westport’s Park & Recreation and several local businesses for their efforts to clean the town’s Pasacreta Park, which honors a police captain who died from cancer in 1976. Over the past 30 years, the site had largely become overgrown, but it was cleaned and re-landscaped this week.

Here’s a link to coverage of the clean-up in the Norwalk Hour.

Tags: Westport

Meriden boasts an impressive collection of military monuments along a nearly quarter-mile stretch of Broad Street (Rte. 5).

Meriden boasts an impressive collection of military monuments along a nearly quarter-mile stretch of Broad Street (Rte. 5).

The largest of the monuments, near the intersection of Broad Street and East Main Street, is the city’s 1930 World War Monument. The monument, by Italian sculptor Aristide Berto Cianfarani, features four figures (representing infantry soldiers, marines, sailors and nurses) at the base of a pointed shaft topped by an allegorical eagle.

An inscription on the western face of the monument’s base reads, “Dedicated to those from Meriden who made the supreme sacrifice in the service of their country during the World War 1917-1918.”

The other faces of the monument’s base list local residents lost in the conflict. Fluting along the column’s shaft and a collection of bronze stars just below the eagle symbolize the United States flag.

Not far from the monument is Meriden’s World War Wall of Honor, which features six large bronze plaques, each with four columns of names.

Not far from the monument is Meriden’s World War Wall of Honor, which features six large bronze plaques, each with four columns of names.

Also near the World War monument is the city’s 1955 World War II Honor Roll, which features two granite monuments with three plaques on each side. Each of the 12 plaques has five columns of names, and a small corrections plaque has been attached to one of the monument’s faces.

Moving south along the Broad Street median, we find a Gold Star monument honoring war heroes. The monument features an eagle and four service emblems on its south face, along with the dedication, “To live in the hearts of those we leave is not to die.”

Just across a gap in the median stands the city’s Marine Corps Monument, which was erected in 1976 by local Marines to honor members’ service on the Corps’ 201st anniversary. The U.S. and Marine Corps flags are displayed near the monument.

A bit further south is Meriden’s Spanish-American War monument, which features a rifle-bearing soldier facing east. A plaque on the monument’s east face has three columns listing the names of residents who served in the conflict.

Continuing south, the next monument honors the service of residents in Korea and Vietnam. A dedication on the east face reads, “In memory of the citizens of Meriden who answered their country’s call.” The left section of the monument lists the 20 residents who fought in Korea, and the right section lists the names of 25 Vietnam veterans.

Continuing south, the next monument honors the service of residents in Korea and Vietnam. A dedication on the east face reads, “In memory of the citizens of Meriden who answered their country’s call.” The left section of the monument lists the 20 residents who fought in Korea, and the right section lists the names of 25 Vietnam veterans.

The last Broad Street monument we’ll look at honors Count Casmir Pulaski, a Polish military commander who emigrated to what would become the United States and became a brigadier general during the American Revolution. Regarded as the father of the American cavalry, Pulaski was killed in 1779 during a siege in Savannah, Ga.

Tags: Meriden

East Hartford honors its Civil War veterans with an 1868 obelisk erected at the highest point of Center Cemetery.

East Hartford honors its Civil War veterans with an 1868 obelisk erected at the highest point of Center Cemetery.

A dedication on the base of the monument’s front (west) face reads, “The Union, it must and shall be preserved.” The west face also bears the U.S. and Connecticut shields, and a decorative element featuring a flag, crossed rifles, a sword and a haversack. The west face also lists Andersonville, the site of a Confederate prison camp in Georgia, and the battle of Cold Harbor (Va.).

Also on the west face, five residents killed during the war are listed by name, regimental affiliation, the location and date of death, and their age.

Also on the west face, five residents killed during the war are listed by name, regimental affiliation, the location and date of death, and their age.

The south face lists six residents, Sharpsburg (Md., where the battle of Antietam took place), and Kingston (Ga.) The base bears the dedication, “All honor to the brave.”

The east face lists six residents, the battles of Petersburg and Drury’s Bluff (both in Virginia) and the dedication, “We mourn the patriot dead.”

The east face lists six residents, the battles of Petersburg and Drury’s Bluff (both in Virginia) and the dedication, “We mourn the patriot dead.”

The north face provides a tangible reminder of the Civil War’s devastating effect on many families and towns. Among the six names listed on the monument, three are from the Flint family: Alvin Flint, who died in 1863 at the age of 58, Alvin Flint, Jr., 17, who was killed in 1862 at Antietam, and George B. Flint, who died in 1864 in Falmouth, Va., at the age of 18.

The north face also lists Antietam and Port Hudson (La.), and a dedication reading, “Erected by voluntary subscription to the memory of the brave men who gave up their lives that the republic might live.”

A short cannon and a stack of cannonballs appear near the northwest corner of the monument. The cannon’s markings are covered by paint.

A deteriorating brownstone eagle was removed from the top of the obelisk in 1996, and replaced with a replica in 2010. (The images without the eagle were taken in 2009.)

East Hartford honors its World War I heroes with a 1929 statue at the corner of a green at the intersection of Central Avenue and Main Street. A dedication on the west face reads,” In honor of the men and women of East Hartford who answered their country’s call to service in the World War. To the dead a tribute, to the living a memory, to posterity a token of loyalty to the flag of their country.

East Hartford honors its World War I heroes with a 1929 statue at the corner of a green at the intersection of Central Avenue and Main Street. A dedication on the west face reads,” In honor of the men and women of East Hartford who answered their country’s call to service in the World War. To the dead a tribute, to the living a memory, to posterity a token of loyalty to the flag of their country.

A plaque on the monument’s east face lists 18 residents who gave their lives in the conflict.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: East Hartford

More than 2400 Confederate prisoners of war and 135 Union guards are buried at Finn’s Point National Cemetery in southern New Jersey.

More than 2400 Confederate prisoners of war and 135 Union guards are buried at Finn’s Point National Cemetery in southern New Jersey.

The National Cemetery, next to Fort Mott State Park in Pennsville, N.J., holds the remains of Confederate prisoners who were held at Fort Delaware, a Civil War prison camp on the Delaware River’s Pea Patch Island.

The 135 Union guards who died during their service at Fort Delaware, most likely from disease, are honored with an 1879 monument that was covered in 1936 with a dome. A dedication at the base of the monument’s front (north) face reads, “Near this stone lie the remains of 135 United States soldiers whose names, so far as known, are hereon inscribed but whose graves cannot be identified. They died for their country.”

The four sides of the monument are inscribed with the name and native state of the Union guards.

The four sides of the monument are inscribed with the name and native state of the Union guards.

The Confederate prisoners are honored with an 85-foot obelisk that was erected in 1910. A dedication plaque on the front (east) face reads, “Erected by the United States to mark the burial place of 2,436 Confederate soldiers who died at Fort Delaware while prisoners of war and whose graves cannot now be individually identified.”

The names and regimental affiliations of the Confederate prisoners are listed on four small plaques in the lower sections of the obelisk, as well as eight larger plaques at the monument’s base.

The northeast section of the cemetery holds the graves of 13 German prisoners who died during World War II while being held at Fort Dix.

The northeast section of the cemetery holds the graves of 13 German prisoners who died during World War II while being held at Fort Dix.

A Gettysburg Address plaque has been erected in the cemetery, as have seven plaques bearings the “Bivouac of the Dead” poem found in a number of military cemeteries and war monuments.

The cemetery also holds the remains of veterans and family members from later conflicts, and remains available for the burial of cremated remains.

A wayside marker near the cemetery’s entrance explains its history, and a binder in a weather-proof display box lists the locations of marked graves.

Fort Delaware was built in 1847 to help defend the port of Philadelphia, and began to hold Confederate prisoners in 1862. Most of the prisoners and guards who died at the fort were buried on the mainland. After the war, Finn’s Point was established as a national cemetery and the remaining deceased who had been buried at the fort were transferred.

The cemetery is next to Fort Mott State Park. The fort was established to provide coastal defenses for the Spanish-American War, and became a New Jersey state park in 1951.

The cemetery is next to Fort Mott State Park. The fort was established to provide coastal defenses for the Spanish-American War, and became a New Jersey state park in 1951.

Sources:

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

Tags: New Jersey

Milford honors the common grave of 46 smallpox-infected Revolutionary War prisoners of war who died in the city in 1777 with a brownstone obelisk.

Milford honors the common grave of 46 smallpox-infected Revolutionary War prisoners of war who died in the city in 1777 with a brownstone obelisk.

The 1852 monument, in Milford Cemetery, honors infected Continental soldiers who were released onto a Milford beach on January 1, 1777 by British forces. Many of the soldiers were able to leave Milford, but nearly a quarter died in the city.

A granite marker attached to the front (south) face of the monument reads, in part, “In honor of 46 American soldiers who sacrificed their lives in struggling for the independence of their country, this monument was erected in 1852 by the joint liberality of the General Assembly, people of Milford and other contributing friends.”

This dedication, which also explains some of the background behind the soldiers’ fate, was attached to the monument later. We’re assuming it was added in 1976 for the nation’s bicentennial, because a similar granite marker at the foot of the monument’s north face that lists Milford soldiers who fought in the revolution bears a 1976 date.

The south face also bears an inscribed Connecticut seal and 13 stars honoring the original colonies.

The south face also bears an inscribed Connecticut seal and 13 stars honoring the original colonies.

The east face of the brownstone obelisk bears an original inscription honoring Capt. Steven Stow, a Milford resident who cared for the infected soldiers unable to travel home. Stow contracted smallpox and died on February 8, 1777 at the age of 51.

The north and west faces list the deceased soldiers, who are buried in a common grave near the monument. The exact location of the grave is being studied by researchers, who are also looking for a time capsule mentioned in the program for the 1852 dedication.

The site has attracted considerable interest lately, with the discovery of a skull belonging to one of the prisoners at the University of Connecticut’s archaeology department. The skull, which belonged to the New Haven County Historical Society, is going to undergo DNA testing before it is buried, most likely in Milford Cemetery.

A marker on Milford’s Gulf Beach, across the harbor from the actual landing site, honors the soldiers.

A marker on Milford’s Gulf Beach, across the harbor from the actual landing site, honors the soldiers.

One of the infected prisoners, Herman Baker of Tolland, died on an East Hartford farm while attempting to return home. His grave is within the Pratt & Whitney complex, and is maintained by the company as a tribute to American soldiers.

Tags: Milford

The grave of Sgt. Herman Baker, who served in the American Revolution, rests within the Pratt & Whitney complex on Willow Street in East Hartford.

The grave of Sgt. Herman Baker, who served in the American Revolution, rests within the Pratt & Whitney complex on Willow Street in East Hartford.

Baker, a Tolland native who is also listed as “Heman” in some accounts, served with the Lexington Alarm, a local company that rushed to help the Minutemen after the revolution began with the 1775 Battle of Lexington-Concord.

Baker was captured by British forces in 1776, and contracted smallpox while in captivity. He was one of 200 infected Continental soldiers released onto Milford’s Gulf Beach on January 1, 1777. While trying to return home, Baker got as far as East Hartford before dying on a farm that, like several others surrounding it, would later be purchased by Pratt & Whitney.

His grave sits on the north side of today’s Willow Street, about a third of a mile east of the intersection with Main Street (if you’re driving toward Rentschler Field or Cabela’s, the grave is on your left).

His grave sits on the north side of today’s Willow Street, about a third of a mile east of the intersection with Main Street (if you’re driving toward Rentschler Field or Cabela’s, the grave is on your left).

The grave site is fenced by black piping, and a plaque placed at the western end of the site in 2004 explains the circumstances of Baker’s death. The site, which is maintained by Pratt & Whitney’s security team also has room for a car to park as well as a stone bench.

We’ll look at a Milford monument honoring 46 smallpox-infected soldiers who were released with Baker on Friday.

Tags: East Hartford

A 1913 granite Civil War monument anchors an impressive collection of war memorials on the Glastonbury Green.

A 1913 granite Civil War monument anchors an impressive collection of war memorials on the Glastonbury Green.

The Standard-Bearer monument honors Capt. Frederick M. Barber, who served in the 16th Regiment of the Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, and other Civil War veterans from Glastonbury. Barber died from wounds suffered during the Battle of Antietam.

A dedication on the front (south) face of the monument reads, “Erected in memory of Capt. Frederick M. Barber and the soldiers of Glastonbury who gave their lives for their country, by Mercy Turner Barber, 1913.”

The east and north faces are blank, but the west face is inscribed with a lengthy dedication reading, “More enduring than this monument will be the memory of their loyal, patriotic devotion to their country. This granite shaft in time will crumble to dust, but the memory of their heroic deeds, the noble sacrifice of their lives, will live in memory’s realm ’till time shall be no more.”

Atop the monument, the standard-bearer has the flag cradled in his left arm, with his right hand ready to draw a sword in defense of the flag.

Atop the monument, the standard-bearer has the flag cradled in his left arm, with his right hand ready to draw a sword in defense of the flag.

The Standard-Bearer is the largest of six monuments on the green. The western-most monument in the collection honors the service of local residents in World War I with a bronze plaque mounted on a granite base. A dedication atop the plaque reads, “In honor of those of the Town of Glastonbury who answered their country’s call to serve humanity.” The plaque, dedicated in 1924, also bears six columns of names and highlights 16 residents who were killed in the conflict.

To the immediate right of the World War I monument is the granite base of a monument, now blank, that once held a plaque.

Next to the blank monument is a granite monument honoring U.S. Air Force Sergeant John Lee Levitow, who was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for taking actions to save his damaged aircraft during the Vietnam War. A detailed account of his heroic actions appears on a bronze plaque in front of the granite marker.

Next to the blank monument is a granite monument honoring U.S. Air Force Sergeant John Lee Levitow, who was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for taking actions to save his damaged aircraft during the Vietnam War. A detailed account of his heroic actions appears on a bronze plaque in front of the granite marker.

A monument to the east of the Standard-Bearer monument honors Korean War veterans, including a local Marine who was killed in the conflict.

The eastern-most monument on the green honors World War II veterans with a dedication reading, “A tribute to the men and women who served their country. In honor of these who gave their lives.” The monument, dedicated in 1950, lists 27 residents who were killed in the conflict.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: Glastonbury