A four-sided sculpture at the base of a flagpole in the center of the Veterans’ Cemetery next to Darien’s Spring Grove Cemetery honors 2,184 veterans from Connecticut and several other states.

A four-sided sculpture at the base of a flagpole in the center of the Veterans’ Cemetery next to Darien’s Spring Grove Cemetery honors 2,184 veterans from Connecticut and several other states.

Many of the veterans buried in the cemetery lived at the nearby Fitch Home for Veterans and Their Orphans, which was the first such facility for veterans when it opened in 1864.

The monument, dedicated in 1936, features four figures representing veterans from the Civil War, the Spanish-American War and World War I. On the west face of the monument, a Civil War soldier is standing with his right arm supported by a rifle. On the east face, a sailor represents veterans of the Spanish-American War. On the south face, a stylized Doughboy figure is standing with his right arm held above his head (the significance of this gesture escapes us). On the north face, there is a muscular figure whose meaning also eludes us. As the Connecticut Historical Society description of the monument phrases it, “The symbolism of the fourth figure is not clear.”

The sculptor, Karl Lang, was a local resident who also contributed to the carvings at Mount Rushmore.

The sculptor, Karl Lang, was a local resident who also contributed to the carvings at Mount Rushmore.

The flagpole sits at the center of a small traffic island and is surrounded by four evergreen bushes. The flagpole also sits at the center of 11 rows of headstones that radiate from the center in eight sections, creating a square pattern that is best appreciated in an aerial view such as this one.

The Fitch Home for Veterans and Their Orphans was founded in 1864 by Benjamin Fitch, a Darien native and dry goods magnate who was one of the nation’s first millionaires by the start of the Civil War. Fitch helped to organize a regiment, and promised to care for any veterans who were wounded in action. In 1864, Fitch donated five acres and $100,000 (an estimated $1.4 million in 2009 dollars) and built a hospital, chapel, library, residence hall and administrative buildings. A year later, the facility expanded to house children who were orphaned by the war.

In 1888, the facility was taken over by the state of Connecticut. The veterans’ home expanded a number of times between then and 1940, when the state moved the facility to a new home in Rocky Hill.

The former chapel building was moved across Norton Avenue in 1950, and is used today by the local VFW post as well as for community and social events. The cemetery was closed to new veteran internments in 1964.

Sources:

Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: Darien

The elaborate Civil War monument at the west end of Waterbury’s green was dedicated in 1884 to honor local residents who served in the conflict, and, uncommonly among monuments of the era, addresses some of the social changes brought about by the war.

The elaborate Civil War monument at the west end of Waterbury’s green was dedicated in 1884 to honor local residents who served in the conflict, and, uncommonly among monuments of the era, addresses some of the social changes brought about by the war.

The monument, nearly 50 feet tall, is topped by an allegorical statue representing Victory. She stands atop a granite column that features four bronze statues representing the fact that people from all walks of life participated in (or were affected by) the war.

The west face, for instance, features a farmer clutching a rifle. On the north side, a seated soldier, with bedroll and rifle handy, is resting. The east face features a laborer with a sword in his hand.

The sculpture on the south face makes a rare reference to the emancipation of slaves by depicting a woman with a book reading to two children — one is white, and the other is African-American. This represents the new educational opportunities possible since the elimination of slavery.

The sculpture on the south face makes a rare reference to the emancipation of slaves by depicting a woman with a book reading to two children — one is white, and the other is African-American. This represents the new educational opportunities possible since the elimination of slavery.

The west face also features a bas-relief sculpture depicting a pitched battle, and the east face displays the naval battle between the ironclad ships the Monitor and the Merrimac.

The south face carries a dedication “in honor of the patriotism and to perpetuate the memory of the more than 900 brave men who went forth from this town to fight in the war for the Union, this monument has been erected by their townsmen that all who come after them may be mindful of their deeds, and fail not in the day of trial to emulate their example.”

The north face bears a somewhat florid poem written by the Rev. Dr. Joseph Anderson:

Brave men, who rallying at your country’s call,

Went forth to fight, if heaven willed, to fall!

Returned, ye walk with us through summer years

And hear a nation say, God bless you all!

Brave men, who yet a heavier burden bore,

And came not home to hearts by grief made sore!

The call you dead, but lo! Ye grandly love,

Shrined in the nation’s love forever more!

The traffic island hosting the monument (a location that hinders careful examination or photography) features four lampposts with shafts that are shaped like cannons with rifles leaning against them.

Source: CHS: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: waterbury

A 1958 granite memorial to veterans of all wars stands at the center of Waterbury’s green. The monument features a multi-faceted base, above which four columns rise. The columns are connected by granite blocks with engraved emblems of the service branches that are varied on the different sides to prevent favoritism among the branches.

A 1958 granite memorial to veterans of all wars stands at the center of Waterbury’s green. The monument features a multi-faceted base, above which four columns rise. The columns are connected by granite blocks with engraved emblems of the service branches that are varied on the different sides to prevent favoritism among the branches.

The east face of the monument bears an inscribed dedication “in honor of all those who served in the wars of our country. The inscription is flanked by markers bearing the names and dates of the American Revolution as well as the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam.

The north face honors the War of 1812 and the Mexican War; the west face honors the Civil and Spanish-American wars; and the south face honors the two World Wars. The north, west and south faces also feature stone eagles sitting above the shield of the United States.

The large round black items near the base of the monument are spotlights, although at a casual glance, they may look like trash cans. The monument is also surrounded by a low evergreen hedge.

The large round black items near the base of the monument are spotlights, although at a casual glance, they may look like trash cans. The monument is also surrounded by a low evergreen hedge.

Near the War Memorial is a Freedom Tree flanked by two sets of monuments in honor of service members who were declared missing in action during in Korea and Vietnam. The Korea monument has four names, and the Vietnam monument has two.

These images of the war memorial were taken in mid-February, when a large menorah still graced the green. The Civil War monument in the background of some images sits at the west end of Waterbury’s green, and will be profiled on Wednesday.

Tags: waterbury

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in West Haven’s Oak Grove Cemetery was dedicated in 1890, when West Haven was still part of Orange. (West Haven was split off from Orange in 1921, and was incorporated as a city in 1961.)

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in West Haven’s Oak Grove Cemetery was dedicated in 1890, when West Haven was still part of Orange. (West Haven was split off from Orange in 1921, and was incorporated as a city in 1961.)

The monument sits in a round traffic island near the center of the cemetery. Inscriptions on the front (south) face bear the years of the Civil War, along with a dedication “erected in honor of our loyal soldiers and sailors.”

The obelisk is topped by a polished granite sphere, and a carved stars-and-stripes motif surrounds the monument just below the polished sphere. The front face also features a three-dimensional bronze sculpture of an eagle surrounded by flags, cannons, crossed swords and oak leaves.

A smaller granite marker at the base of the monument was dedicated in 1964 by a local VFW post. The inscription reads “In grateful tribute to the living and the dead who through their valiant effort and supreme sacrifice have helped to preserve us a free nation.”

The curbing around the monument bears of the names of several Civil War veterans who were originally buried near the monument, but who were moved in subsequent years.

The curbing around the monument bears of the names of several Civil War veterans who were originally buried near the monument, but who were moved in subsequent years.

Tags: West Haven

The armistice monument on West Haven’s green was dedicated in 1928 to honor local residents who died in World War I. Over the years, the monument and its surroundings have been revamped and rededicated to honor heroes of later conflicts, including the current war in Iraq.

The armistice monument on West Haven’s green was dedicated in 1928 to honor local residents who died in World War I. Over the years, the monument and its surroundings have been revamped and rededicated to honor heroes of later conflicts, including the current war in Iraq.

The monument, on the Main Street (north) side of the green, is topped by an 11-foot bronze statue of a doughboy solider, who stands atop a granite base holding a rifle in one hand and a helmet in the other, outstretched, arm. (The origins of the term “doughboy” vary, but it apparently referred to infantry troops during the Civil War. During the first world war, U.S. troops adopted it as a nickname for themselves and its meaning expanded to all branches of the service.)

The West Haven doughboy was sculpted by Anton Schaff, who also created a number of war memorials in New York and New Jersey, as well as several Confederate busts at Vicksburg (MS) National Military Park.

A plaque on the front face of the West Haven’s monument’s base features four military figures (soldiers, an airman and a sailor) gathering with four civilians laborers and a dedication “to the memory of those who gave their lives in the great war 1917-1918.”

A plaque on the front face of the West Haven’s monument’s base features four military figures (soldiers, an airman and a sailor) gathering with four civilians laborers and a dedication “to the memory of those who gave their lives in the great war 1917-1918.”

Beneath the dedication is the American’s Creed, a pledge, similar to the Pledge of Allegiance, that was adopted by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1917.

The other three faces of the monument’s base bear bronze plaques listing the names of 29 West Haven residents who died in World War I. Over the years, additional plaques were added to honor the residents who served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam, and smaller plaques reading “for those who gave their lives – World War I” were affixed to the bottom of the original plaques.

Near the base of the monument, a separate granite marker has been dedicated to the memory of Thomas E. Vitagliano, 33, an Army staff sergeant who grew up in West Haven and Orange. Vitagliano and another soldier were killed Jan. 17, 2005 by an improvised vehicle explosive device in Iraq.

West Haven’s firefighters are honored by a bell-topped monument not far from the doughboy statue.

Tags: West Haven

A monument to Uncas, the first Sachem of the Mohegan tribe, marks his burial in what remains of a Native American cemetery in Norwich.

A monument to Uncas, the first Sachem of the Mohegan tribe, marks his burial in what remains of a Native American cemetery in Norwich.

Uncas, who died in 1683, led the Mohegans after they split from the Pequot tribe over issues including strategies for responding to the arrival of English settlers and tribal succession planning. Uncas favored collaborating with the settlers, while a faction of Pequots led by Sachem (head chief) Sassacus preferring fighting over land and control of the local fur trade.

The Uncas monument sits in a small burial ground on Sachem Street. The square base of the monument was dedicated in 1833, with President Andrew Jackson participating in the dedication ceremonies. The granite column was dedicated nine years later in 1842, after organizers had resolved several problems with the monument, including quarrying granite that met their specifications and reaching a consensus on the proper spelling of “Uncas.”

The dedication ceremony was marked by several speeches praising Uncas for his cooperation with the settlers, but for some reason, no Mohegans were invited to participate. Organizers apparently assumed the tribe was extinct, and didn’t know that survivors were living in nearby Montville.

The dedication ceremony was marked by several speeches praising Uncas for his cooperation with the settlers, but for some reason, no Mohegans were invited to participate. Organizers apparently assumed the tribe was extinct, and didn’t know that survivors were living in nearby Montville.

“Buffalo Bill” Cody laid a wreath at the Uncas monument in 1907 when his Wild West stunt show visited Norwich.

The Mohegan’s burial ground may have covered as many as 16 acres over what is now a well-developed residential neighborhood. Today, a sixteenth of an acre remains.

In 2008, the Mohegans dedicated a memorial to ancestors whose graves were lost to redevelopment of the burial ground on the site of a former Masonic lodge near the Uncas monument.

Tags: Norwich

Two monuments in Fairfield commemorate the Great Swamp Fight, during which English settlers defeated Native Americans on July 13, 1637.

Two monuments in Fairfield commemorate the Great Swamp Fight, during which English settlers defeated Native Americans on July 13, 1637.

The Swamp Fight was the last major action in a series of battles between the Pequot tribe and English settlers over land and trade in southern New England and Long Island Sound.

During a massacre in Mystic on May 26, 1637, an estimated 600 Pequots died after settlers and allied Mohegans (who had separated from the Pequots earlier in the century) burned an occupied fort and shot people trying to escape the fire.

A group of Pequot survivors who had occupied another fort traveled west after the massacre and sought sanctuary in marshlands in today’s Fairfield. The last 100 warriors within that group were defeated on July 13 after 180 noncombatants were allowed to surrender. By September of 1638, a treaty had divided the surviving Pequots among rival tribes and settlers who used them as slaves.

The Swamp Fight Monument, dedicated in 1904 by the Connecticut Society of Colonial Wars, today sits on a small triangle of land along the Post Road, near a Peoples’ United Bank branch and a popular Dunkin’ Donuts outlet. A large stone monument bears the simple inscription on its east face that “the great Swamp Fight here ended the Pequot War.”

The Swamp Fight Monument, dedicated in 1904 by the Connecticut Society of Colonial Wars, today sits on a small triangle of land along the Post Road, near a Peoples’ United Bank branch and a popular Dunkin’ Donuts outlet. A large stone monument bears the simple inscription on its east face that “the great Swamp Fight here ended the Pequot War.”

This inscription is much more sedate than some of the historical texts written during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which tended to describe the Native Americans with less-than-glowing terms.

The only other marking on the stone lists its dedication date.

Much of the land where the Swamp Fight took place has been lost to development, including the construction of Interstate 95. Driving along the interstate just past exit 19, you can see marsh plants rising above the small surviving portions of the swamp.

Researchers from the Mashantucket Pequot Museum plan to survey the Southport area over the next couple of years to try to identify locations or relics from the areas where the battle took place.

The Swamp Fight is also commemorated by a fountain, dedicated in 1903 by the Daughters of the American Revolution, that sits at the intersection of Main Street and Harbor road in the Southport section of Fairfield. The fountain, topped by a light fixture, features water-spigot lions on the north and south faces. Since we visited this monument in mid-February, we’re not sure if it has been converted into a planter, as many commemorative fountains from that era have been.

The Swamp Fight is also commemorated by a fountain, dedicated in 1903 by the Daughters of the American Revolution, that sits at the intersection of Main Street and Harbor road in the Southport section of Fairfield. The fountain, topped by a light fixture, features water-spigot lions on the north and south faces. Since we visited this monument in mid-February, we’re not sure if it has been converted into a planter, as many commemorative fountains from that era have been.

The water trough on the north side of the monument bears the inscription “This fountain commemorates the valor and victory of the colonist forefathers at the Pequot Swamp,” which is a slightly more strident message in praise of the settlers than the matter-of-fact listing found on the other Swamp Fight monument.

Sitting in a T-shaped intersection, the fountain is an example of the middle-of-the-roadway sculpture dreaded by monument bloggers, who generally prefer to take pictures while standing on the safety of a town green.

Sitting in a T-shaped intersection, the fountain is an example of the middle-of-the-roadway sculpture dreaded by monument bloggers, who generally prefer to take pictures while standing on the safety of a town green.

Sources:

Tags: Fairfield, Native Americans, Southport

We conclude this week’s look at the monuments around the Naugatuck Town Green with the impressive Veterans’ Monument located at the northeast corner of the green, not far from the Civil War-era Soldiers’ Monument.

We conclude this week’s look at the monuments around the Naugatuck Town Green with the impressive Veterans’ Monument located at the northeast corner of the green, not far from the Civil War-era Soldiers’ Monument.

The monument features a central slab dominated by an eagle, the emblems (in stone and bronze) of the armed services and the inscription “Naugatuck honors the men and women who served their country in time of need.” The center column is flanked by four smaller slabs listing military conflicts since World War II, along with the names of local residents who died in those conflicts.

The two columns listing residents lost in World War II carry 71 names. The Korea section lists five names, and the Vietnam section lists six names.

The Lebanon section recognizes Dwayne W. Wigglesworth, who died in the 1983 Marine barracks bombing, and the Iraq section recognizes David T. Friedrich, an Army reservist who was killed in a 2003 mortar attack on his base.

The Lebanon section recognizes Dwayne W. Wigglesworth, who died in the 1983 Marine barracks bombing, and the Iraq section recognizes David T. Friedrich, an Army reservist who was killed in a 2003 mortar attack on his base.

The monument also lists conflicts that aren’t commonly mentioned on local monuments, such as Grenada, Panama and Kosovo.

Kudos to the Naugatuck Veterans Committee for recognizing the military contributions made on the nation’s behalf, regardless of the size or scope of the conflict.

Tags: Naugatuck

Naugatuck’s World War Monument is located on Meadow Street, northwest of the Soliders’ Monument in the center of the Town Green. The monument, which was dedicated in 1921, features a large marble rectangular flagpole base that sits in a small park next to Salem School.

The front (or east) face of the monument bears the inscription “Victory is consecrated by a righteous peace” and two allegorical figures that most likely represent military strength and the importance of education.

The rear (or west) face of the monument reads “In honor of the men of Naugatuck who gave their lives in the great war for the chaining of savagery and the liberation of a menaced world,” and carries the names of 30 local residents who were killed in the war.

The south face reminds us that “Armed and absolute might triumphs through unselfish valor,” while the north face states “In

time of peril the state is fortified by discipline learned in peace.” Both of these messages are topped by designs depicting fruit and ribbons draped between two ram heads (the symbolism of which extends beyond our experience).

The monument was sculpted by Evelyn Beatrice Longman, whose other works include the “Golden Boy” statue that long served as a corporate symbol for AT&T. She also sculpted the Spanish-American War memorial in Hartford’s Bushnell Park, decorative elements on the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, and a variety of other works.

Near the World War Monument, a flagpole in front of Salem School serves as a monument to the Spanish-American War in 1898. A plaque at the base of the flagpole commemorates the USS Maine, which sunk in Havana’s harbor after an explosion of an undetermined cause. An identical plaque adorns a memorial in Bridgeport’s Seaside Park.

Tags: Naugatuck

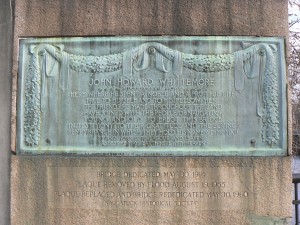

The Maple Street bridge across the Naugatuck River was dedicated in 1914 to John Howard Whittemore, a local industrialist and philanthropist who died in 1910. Whittemore founded the Naugatuck Malleable Iron Company, which became Naugatuck’s largest employer during the post-Civil War boom. The company supplied iron for railroads, carriage makers and producers of shears, among other industries.

The Maple Street bridge across the Naugatuck River was dedicated in 1914 to John Howard Whittemore, a local industrialist and philanthropist who died in 1910. Whittemore founded the Naugatuck Malleable Iron Company, which became Naugatuck’s largest employer during the post-Civil War boom. The company supplied iron for railroads, carriage makers and producers of shears, among other industries.

Whittemore, who was also a director of the New York, New Haven and Hartford railroad, donated a number of buildings to Naugatuck, including the 1893 Salem School, the Congregational Church and the Howard Whittemore Library, which was named after a son. He also played a role in raising funds for the local high school, the Soldiers’ Monument on the green and other local institutions and private causes.

Whittemore’s firm, now named the Eastern Company, continues to supply industrial hardware, security equipment and metal castings.

Whittemore Glen State Park, on the border between Naugatuck and Middlebury, was once part of the Whittemore’s land holdings.

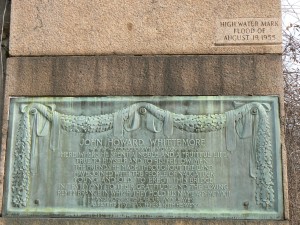

The bridge, which bears a plaque honoring Whittemore on the northwest abutment, also serves as a memorial to the devastating floods that hit the Naugatuck River Valley on August 19, 1955. Just above the Whittemore plaque is a notch, eight feet and two inches above the sidewalk, marking the crest of the flood in Naugatuck.

The bridge, which bears a plaque honoring Whittemore on the northwest abutment, also serves as a memorial to the devastating floods that hit the Naugatuck River Valley on August 19, 1955. Just above the Whittemore plaque is a notch, eight feet and two inches above the sidewalk, marking the crest of the flood in Naugatuck.

The flooding occurred when two hurricanes struck the state within five days of each other and flooded most of the state’s communities. As a smaller river, the Naugatuck did not have flood monitoring equipment of controls found on some larger rivers, which increased the damage to riverside and downtown sections of many of the area’s communities.

In Naugatuck, four people were killed, while further north in Waterbury, 29 people died in the floods.

Additional information about the 1955 floods is available from the Connecticut State Library. The Derby page on the Electronic Valley Web site has information and images about the flood damage in that town and there are a number of images of Waterbury at this site.

Additional information about the 1955 floods is available from the Connecticut State Library. The Derby page on the Electronic Valley Web site has information and images about the flood damage in that town and there are a number of images of Waterbury at this site.

Tags: Naugatuck