Waterford honors veterans of the nation’s wars with a collection of monuments in two local parks.

Waterford honors veterans of the nation’s wars with a collection of monuments in two local parks.

Three monuments are featured in a small green in War Memorial Park on Rope Ferry Road (Route 156), near the intersection with Great Neck Road (Route 213).

A bronze plaque on a 1975 monument honors local residents who served in the American Revolution. The plaque bears a dedication reading, “To honor those patriots from the land now Waterford who courageously responded beginning with the Lexington Alarm in the War of Independence, 1775–1783.”

The plaque list nearly 80 names of residents who served in the revolution. At the time, Waterford, incorporated as a town in 1801, was part of New London.

The plaque list nearly 80 names of residents who served in the revolution. At the time, Waterford, incorporated as a town in 1801, was part of New London.

To the west of the American Revolution memorial, a monument honors Waterford’s Civil War and Spanish-American War veterans. The monument’s dedication includes similar language to the American Revolution Memorial, praising the courage of residents who served in the conflicts and including the starting and ending dates of the wars.

The Civil War section of the monument includes nearly 110 names, and the Spanish-American War section lists 10 names.

A memorial flagpole next to the monument includes the emblems of the military branches in its base.

A memorial flagpole next to the monument includes the emblems of the military branches in its base.

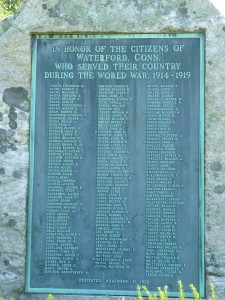

At the western end of the green, a World War I monument was dedicated in 1928. The dedication plaque contains three columns of names, and highlights five residents who died during their World War service.

Veterans Memorial Green

A little more than a half-mile east of War Memorial Park, Waterford’s veterans are further honored with Veterans Memorial Green on the grounds of Town Hall.

The green, at the intersection of Route 156 and Boston Post Road (Route 1), was dedicated in 1997. A granite monument bears an inscription reading, “Dedicated to all the men and women who served in the armed services of the United States of America.” In addition to a engraved eagle, the monument also features bronze service emblems.

The green, at the intersection of Route 156 and Boston Post Road (Route 1), was dedicated in 1997. A granite monument bears an inscription reading, “Dedicated to all the men and women who served in the armed services of the United States of America.” In addition to a engraved eagle, the monument also features bronze service emblems.

The plaza surrounding the memorial, dedicated in 2008, has been designated “a path of honor.” The plaza features memorial bricks inscribed with the names of local veterans.

Tags: Waterford

Middletown was one of several Connecticut communities that honored the 10th anniversary of the September 11 attacks Sunday by dedicating a portion of a steel beam recovered from one of the World Trade Center towers.

Middletown was one of several Connecticut communities that honored the 10th anniversary of the September 11 attacks Sunday by dedicating a portion of a steel beam recovered from one of the World Trade Center towers.

The beam was placed on display outside South Fire District headquarters on Randolph Road (Route 155).

Ceremonies commemorating the attacks were held state-wide, and sections of WTC beams were dedicated in Easton, Enfield, Manchester, Middletown, Ridgefield, Woodbridge and Stafford, and likely other communities as well.

Tags: Middletown

Dartmouth College traces its roots to an 18th Century school for Native Americans in a section of Lebanon that later became the town of Columbia.

Dartmouth College traces its roots to an 18th Century school for Native Americans in a section of Lebanon that later became the town of Columbia.

Moor’s Charity School was founded in 1754 by Congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock to provide a Christian education to Native Americans and to English students who would serve Native American tribes as teachers and missionaries. The school was named after donor Joshua Moor of Mansfield.

Classes moved from Wheelock’s home a year later to a schoolhouse that was remodeled in the 1850s, and today stands a short distance from the church and Columbia’s town hall. The schoolhouse was moved several times, and was placed in its current location in 1948.

Moor’s School had difficulty recruiting students in its Connecticut location, and moved to New Hampshire in 1769.

Moor’s School had difficulty recruiting students in its Connecticut location, and moved to New Hampshire in 1769.

A plaque near the schoolhouse entrance reads, “Moor’s Charity School, 1755-1769, Columbia, Connecticut. Proudly remembered for 200 years by generations of Dartmouth men as seeding ground for Dartmouth College and and faithful steward of Eleazar Wheelock’s generous and crusading spirit. May 17, 1969.”

The school is also honored with a granite monument in front of the Congregational Church on Route 87. An inscription on the monument reads, “In 1755, Eleazar Wheelock, DD, minister at Lebanon Crank (now Columbia) founded near this spot Moor’s Indian Charity School. In 1769 the school was removed to Hanover, New Hampshire. From this beginning arose Dartmouth College, Eleazar Wheelock, president 1769-1779. Erected by the Connecticut Society of the Colonial Dames of America, 1949.”

Tags: Columbia

Columbia honors its war veterans and other public servants with memorials in its historic town center.

Columbia honors its war veterans and other public servants with memorials in its historic town center.

Columbia’s veterans are honored with memorials in front of its Yeoman’s Hall municipal building on Jonathan Trumbull Highway (Route 87), near the intersection with Middletown Road (Route 66).

The largest memorial is a Honor Roll monument, dedicated in 1956, listing Columbia’s World War II veterans. The monument, with an engraved eagle on its southwest face, lists about 120 names on its southwest and northeast faces.

Next to the World War II memorial is a 1919 Honor Roll monument to the town’s World War I veterans. The monument, featuring a bronze plaque mounted on a boulder, lists 18 names. The plaque also bears a dedication reading, “In honored memory of the men of Columbia who served during the World War.”

Next to the World War II memorial is a 1919 Honor Roll monument to the town’s World War I veterans. The monument, featuring a bronze plaque mounted on a boulder, lists 18 names. The plaque also bears a dedication reading, “In honored memory of the men of Columbia who served during the World War.”

Near the war monuments, a memorial honors State Trooper Russell A. Bagshaw, a Columbia native killed in the line of duty in 1991 at the age of 28. Trooper Bagshaw interrupted a burglary at a Windham sporting goods store, and was ambushed in his cruiser.

On the nearby town green, a monument dedicated in 1997 marks the 50th anniversary of the Columbia Volunteer Fire Department.

Tags: Columbia

Willimantic honors residents killed in the World Wars and Vietnam with a downtown park and memorial.

Willimantic honors residents killed in the World Wars and Vietnam with a downtown park and memorial.

Memorial Park, on Main Street (Routes 32 and 66) between Watson and Tingley streets, features a large monument dedicated in 1953. The monument features three archways that bear memorial plaques honoring Willimantic’s war heroes.

The central archway features a bronze plaque reading, “Dedicated to the men of the City of Willimantic, Connecticut, who made the supreme sacrifice in the cause of freedom…in the flaming crucible of war. These patriots laid down their lives that all the peoples of the earth might dwell together in peace.”

The central archway also has a plaque honoring the service of Willimantic’s Vietnam veterans.

The central archway also has a plaque honoring the service of Willimantic’s Vietnam veterans.

The plaque in the right (eastern) bears the names of 56 residents lost during World War II.

The plaque in the left archway lists 29 residents who died while serving in World War I.

A boulder near the memorial bears a 1919 plaque honoring the service of local National Guard troops who served in World War I.

Tags: Willimantic, Windham

The Frog Bridge in the Willimantic section of Windham provides a quirky look at the town’s history.

The Frog Bridge in the Willimantic section of Windham provides a quirky look at the town’s history.

Officially named the Tread City Crossing, the bridge connects Main Street (Route 66) and Pleasant Street (Route 32), and crosses the Willimantic River.

But the bridge, which opened in 2000, is more commonly known for its decorative elements, including the 11-foot bronze frogs at the bridge’s northern and southern ends and the large thread spools lining the bridge.

The spools symbolize Willimantic’s historic importance as a thread production center, and several former mill buildings (since converted to other uses) can be seen from the bridge’s sidewalks.

The spools symbolize Willimantic’s historic importance as a thread production center, and several former mill buildings (since converted to other uses) can be seen from the bridge’s sidewalks.

The frogs symbolize the 1754 Frog Fight, a curious incident from Willimantic’s history. According to local legend, Willimantic residents, concerned about attacks from French forces or Native Americans, were awakened during a hot June night by loud, strange noises coming from the woods. Residents grabbed muskets and waited all night for an attack that didn’t come.

The next morning, the noises were attributed to thousands of frogs fighting over the last remnants of water in a nearly dried-out millpond. Residents were initially embarrassed about the incident, but later adopted frogs an unofficial mascot of Willimantic.

Tags: Willimantic, Windham

Coventry honors its Civil War veterans with a simple monument in Nathan Hale Cemetery.

Coventry honors its Civil War veterans with a simple monument in Nathan Hale Cemetery.

The undated Civil War monument, near the monument honoring Hale, features a 30-pounder Parrott Rifle mounted on a granite base.

A dedication on the east face of the monument’s base reads, “Veterans, 1861-1865.”

Next to the cannon is a triangular metal bracket that once held a pyramid of shells for the cannon. The fate of the shells is not recorded, but many Civil War cannonballs and shells were removed from monuments during World War II and donated to scrap metal drives.

The Coventry Parrott Rifle was forged in 1862 at the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, New York. Similar cannon from the foundry can be seen near monuments in Derby, Ansonia and other Connecticut towns.

The Coventry Parrott Rifle was forged in 1862 at the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, New York. Similar cannon from the foundry can be seen near monuments in Derby, Ansonia and other Connecticut towns.

The town of Coventry’s Veterans Memorial Commission hopes to restore the appearance of the rusted cannon and to replace its existing base.

Tags: Coventry

Nathan Hale is honored in his hometown of Coventry with a large monument in a cemetery that also bears his name.

Nathan Hale is honored in his hometown of Coventry with a large monument in a cemetery that also bears his name.

The 1846 monument, near the entrance to Nathan Hale Cemetery on Lake Street, is a 45-foot-tall granite obelisk with Egyptian-themed decorative elements.

A dedication on the monument’s east face reads, “Captain Nathan Hale, 1776.” The north face has an inscription reading, “Born at Coventry, June 6, 1755.”

The west face displays the famous quotation cited as Hale’s final words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

The south face reads, “Died at New York, Sept. 22, 1776.”

The south face reads, “Died at New York, Sept. 22, 1776.”

The monument was designed by New Haven architect Henry Austin. At the time of its dedication, some criticized the monument for being large and immodest.

Fundraising for the monument began in 1837, and the monument was dedicated in 1846. The monument was restored in 1890s, and in 1923, the monument was transferred to the State of Connecticut.

A wayside marker near the monument provides information about Hale’s life and the cemetery.

Hale, a Coventry native and Yale graduate, taught in East Haddam and New London before volunteering to serve as a spy in New York in 1776. Hale was captured and hanged by the British, and his body was buried in an unrecorded location.

Hale, a Coventry native and Yale graduate, taught in East Haddam and New London before volunteering to serve as a spy in New York in 1776. Hale was captured and hanged by the British, and his body was buried in an unrecorded location.

Hale, designated as Connecticut’s official hero in 1985, is honored with statues in New London’s Williams Park, the Yale campus, the state capitol, New Haven’s Fort Nathan Hale, and with a bust in East Haddam. His Coventry home is maintained as a museum.

The town of Coventry plans to dedicate a statue of Hale next year as part of celebrations commemorating the 300th anniversary of the town’s founding.

Tags: Coventry

Ellington honors its veterans and war heroes with a pair of monuments on the town green.

Ellington honors its veterans and war heroes with a pair of monuments on the town green.

Veterans of World War I and earlier conflicts are honored with a granite monument, dedicated in 1926, near the intersection of Maple Street (Route 140) and Main Street (Route 286).

A bronze marker on the monument’s east face bears the inscription, “Ellington Remembers,” and includes seals of Connecticut, the United States and the town.

The plaque’s east face lists residents who served in the American Revolution and World War I, and highlights three residents who died during their World War I service.

The west face of the monument also bears the seals seen on the east face. A bronze plaque lists Ellington residents who served in Colonial era wars in 1675 and 1763, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War in 1846, the Civil War (referred to as the “War of the Rebellion”), and the Spanish-American War.

The Civil War section includes the names of nearly 150 residents who served.

The Civil War section includes the names of nearly 150 residents who served.

Immediately to the west of the memorial, a monument honors Ellington’s veterans of later wars. An inscription on the monument’s east face reads, “In memory of those who served their country. World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Grenada, Lebenon [sic], Panama, Desert Storm, Desert Shield.”

Further west on the green, a symbolic Liberty Pole was erected in 1975. Liberty Poles were used before the American Revolution as gathering spots and to invite people to take part in discussions or protests. In many communities, patriots would display a banner on a pole to summon residents.

A small granite marker near the Liberty Pole marks the location of Ellington’s first meetinghouse, which was built in 1739.

Tags: Ellington

Vernon honors its veterans with a memorial hall and several monuments in the heart of its Rockville section.

Vernon honors its veterans with a memorial hall and several monuments in the heart of its Rockville section.

Construction began for Memorial Hall in 1889, and the building was finished a year later. The building originally contained a meeting hall for the local Grand Army of the Republic chapter, a courtroom and municipal offices.

Today, the former GAR meeting space is largely occupied by the New England Civil War Museum (which we’ll highlight in a future post), and the building continues to host municipal offices and a legislative chamber.

The brownstone and brick building, on Park Street, features a number of large arched windows and ornamental details.

The west side of the Memorial Building, for example, includes large stained glass windows on the second floor. The windows are topped on the exterior with brownstone insets displaying an eagle flanked by the Connecticut and United States shields.

The west side of the Memorial Building, for example, includes large stained glass windows on the second floor. The windows are topped on the exterior with brownstone insets displaying an eagle flanked by the Connecticut and United States shields.

The southeast corner features a tower topped by a turret with large windows and copper ornamentation at its peak.

A smaller United States shield can be seen near the archway over the building’s front entrance.

A plaque in the building’s lobby commemorates Rockville native Gene Pitney, a singer and songwriter who was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2002.

Central Park

Immediately across Park Street from the Memorial Building, a collection of monuments honor Vernon’s veterans of the World Wars, Korea and Vietnam.

The central monument bears an inscription reading, “Dedicated to the honor and memory of the men and women of the Town of Vernon who so gallantly served their country in World Wars.”

The central monument bears an inscription reading, “Dedicated to the honor and memory of the men and women of the Town of Vernon who so gallantly served their country in World Wars.”

To the west of the World War memorial, a monument honors Vernon residents who served in Vietnam. The granite monument bears the names of seven residents who died in the war.

To the east, a monument honors Vernon’s Korean War veterans, and commemorates one resident killed during the conflict.

At the eastern end of the park, a fountain honors William T. Cogswell, a 19th century builder who published a history of Rockville in 1872. The memorial is a 2005 copy of a fountain erected in 1883 by Cogwell’s cousin, a San Francisco dentist, investor and ardent temperance advocate.

The San Francisco Cogswell erected at least nine fountains in different cities depicting himself, and inscriptions on the base advocated temperance.

The San Francisco Cogswell erected at least nine fountains in different cities depicting himself, and inscriptions on the base advocated temperance.

Within two years of its dedication, the Rockville fountain had been stolen and dumped in a local lake. The fountain was recovered, stolen and recovered again before being donated to a World War II scrap metal drive.