Connecticut honors Civil War veterans held in Confederate prisoner of war camps with a statue on the grounds of the state capitol.

Connecticut honors Civil War veterans held in Confederate prisoner of war camps with a statue on the grounds of the state capitol.

The “Andersonville Boy” statue, dedicated in 1907, honors the state’s Civil War POWs. A dedication on the monument’s east face reads, “In memory of the men of Connecticut who suffered in Southern military prisons, 1861-1865.”

The monument depicts a young soldier wearing a simple frock coat and holding a hat in his left hand.

The monument was created by sculptor Bela Pratt, whose other works include a notable statue of Nathan Hale on the Yale campus in New Haven.

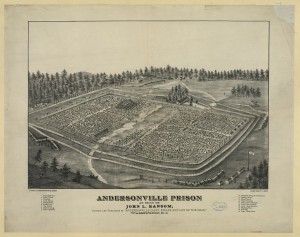

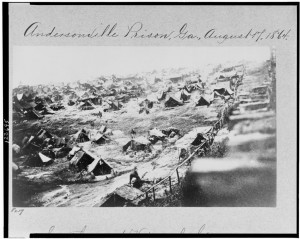

The Hartford statue is a copy of a monument dedicated at the same time at the site of the Andersonville prison camp in Georgia. During the war, nearly 13,000 of the 45,000 Union prisoners held at the camp died from disease and malnutrition. The camp was known for overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions.

The Hartford statue is a copy of a monument dedicated at the same time at the site of the Andersonville prison camp in Georgia. During the war, nearly 13,000 of the 45,000 Union prisoners held at the camp died from disease and malnutrition. The camp was known for overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions.

The illustrations depicting the prison camp are from the Library of Congress.

A monument in Norwich’s Yantic Cemetery honors Civil War veterans from the city who died at Andersonville.

Next to the Andersonville Boy monument is a statue honoring Clarence Ransom Edwards, an Ohio native who commanded a World War I division comprised of National Guard troops from New England states. The Edwards memorial, dedicated in 1942, was created by sculptor George H. Snowden.

Next to the Andersonville Boy monument is a statue honoring Clarence Ransom Edwards, an Ohio native who commanded a World War I division comprised of National Guard troops from New England states. The Edwards memorial, dedicated in 1942, was created by sculptor George H. Snowden.

Tags: Hartford

Westport honors the veterans of the 20th Century Wars with a collection of monuments on a downtown green.

Westport honors the veterans of the 20th Century Wars with a collection of monuments on a downtown green.

Veteran’s Memorial Green, between Main Street and Myrtle Avenue, includes monuments honoring the service of local residents in the two World wars, Korea and Vietnam.

The World War I monument features a bronze Doughboy atop a granite base. A bronze shield on the south face reads, “Dedicated to the citizens of Westport who served in the World War. Erected Nov. 11, 1930.”

Plaques on the west and east sides of the monument’s base list Westport residents who served in the conflict, with the west plaque honoring seven residents who were killed, and the east plaque honoring seven who served as nurses.

Plaques on the west and east sides of the monument’s base list Westport residents who served in the conflict, with the west plaque honoring seven residents who were killed, and the east plaque honoring seven who served as nurses.

The Doughboy atop the monument was created by sculptor J. Clinton Shepherd, whose other works include a wide range of Western-themed sculptures.

The monument was located on Old Post Road until it was moved to the green in 1987.

Immediately next to the World War I monument, a monument honors the service of Westport’s World War II heroes. A plaque mounted on a rough boulder bears the dedication, “They honored us more than we can ever honor them,” and lists about 42 residents who died during World War II service.

Immediately next to the World War I monument, a monument honors the service of Westport’s World War II heroes. A plaque mounted on a rough boulder bears the dedication, “They honored us more than we can ever honor them,” and lists about 42 residents who died during World War II service.

The monument is flanked by smaller markers honoring Westport’s Korea and Vietnam war veterans. The Vietnam plaque lists five residents killed in the conflict.

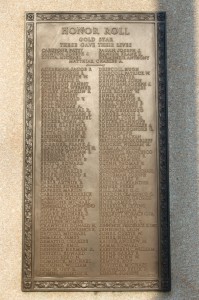

To your left (as you face the monuments), an Honor Roll monument dedicated in 1998 recognizes Westport’s World War II veterans. Five large plaques, each with three rows of names in small print, list local residents who served in the war.

Tags: Westport

Norwalk honors its Civil War veterans with a monument in Riverside Cemetery.

Norwalk honors its Civil War veterans with a monument in Riverside Cemetery.

The Soldiers’ Monument, dedicated in 1889, features a granite base in the middle of a plot reserved for local veterans. A dedication on the monument’s east face reads, “In honor of our dead comrades who fought to save the Union in the War of 1861-1865. Erected by Buckingham Post No. 12, Dept. of Conn., G.A.R (Grand Army of the Republic), 1889.”

The monument is surrounded by 32 graves of Civil War veterans who served in regiments from states including Connecticut, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

The monument was originally topped by a zinc figure depicting a Civil War soldier. The figure was removed in 2002 after extensive deterioration and vandalism that included the theft of the soldier’s rifle.

The monument was originally topped by a zinc figure depicting a Civil War soldier. The figure was removed in 2002 after extensive deterioration and vandalism that included the theft of the soldier’s rifle.

The Norwalk Historical Society is raising funds to restore the figure and return it to Riverside Cemetery.

Nine veterans of the Spanish-American War are buried not far from the Civil War plot, and other nearby plots are dedicated to veterans of later wars.

Norwalk Civil War veterans are also honored with a monument in South Norwalk.

Norwalk’s use of a zinc soldier atop a granite base was unique in Connecticut. Stratford dedicated an all-zinc Civil War monument in 1889 that, like the Riverside Cemetery monument, has suffered from deterioration over the years because zinc turns brittle in cold weather. Zinc monuments often have difficulty supporting their own weight.

Norwalk’s use of a zinc soldier atop a granite base was unique in Connecticut. Stratford dedicated an all-zinc Civil War monument in 1889 that, like the Riverside Cemetery monument, has suffered from deterioration over the years because zinc turns brittle in cold weather. Zinc monuments often have difficulty supporting their own weight.

The Civil War monuments in White Plains, New York, and Orleans, Massachusetts, feature zinc soldiers atop granite bases.

Tags: Norwalk

New Preston honors its Civil War veterans with a monument in New Preston Village Cemetery.

New Preston honors its Civil War veterans with a monument in New Preston Village Cemetery.

The undated monument stands near the Baldwin Hill Road entrance to the cemetery, which is in the New Preston section of Washington.

A dedication on the monument’s east face reads, “A memorial to the soldiers who served faithfully and honorably in the Civil War, 1861-1865. Erected by a comrade, Major Walter Burnham.”

A small cannon has been mounted near the east side of the monument’s base.

The monument’s west face lists 23 Civil War veterans buried in the cemetery.

The monument’s west face lists 23 Civil War veterans buried in the cemetery.

Information about the monument’s designer or supplier hasn’t come to light.

Walter Burnham, a local carriage and wagon manufacturer, sponsored the monument. Burnham served in the Second Connecticut Heavy Artillery regiment, and was wounded during the 1864 Battle of Cedar Creek (in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.)

The steeple visible to the west of the cemetery belongs to the New Preston Congregational Church.

Tags: New Preston, Washington

The grave of American Revolution hero Col. William Ledyard is marked with a granite obelisk in the Groton cemetery that bears his name.

The grave of American Revolution hero Col. William Ledyard is marked with a granite obelisk in the Groton cemetery that bears his name.

The monument honoring Ledyard was erected in 1854 next to the original slate gravestone, which had been damaged by souvenir hunters following the colonel’s death during the 1781 Battle of Groton Heights at nearby Fort Griswold.

The monument’s front (west) face bears Ledyard’s name and a sword, symbolizing Ledyard being killed with his own sword after handing over to a British officer while surrendering the fort.

A dedication on the monument’s west face reads, “Sons of Connecticut, behold this Monument and learn to emulate the virtue, valor and patriotism of your ancestors.”

A dedication on the monument’s west face reads, “Sons of Connecticut, behold this Monument and learn to emulate the virtue, valor and patriotism of your ancestors.”

The monument’s south face has an inscription reading, “Erected in 1854 by the State of Connecticut in remembrance of the painful events that took place in the neighborhood during the War of the Revolution. It commemorates the Burning of New London, the storming of Groton Fort, the massacre of the Garrison and the slaughter of Ledyard, the brave commander of these posts who was slain by the Conquerors with his own sword. He fell in the service of his country, fearless of death and prepared to die.”

The monument’s north face, now difficult to read, is inscribed with the text of Ledyard’s original headstone. After the dedication of the 1854 monument, that stone was enclosed in a granite marker with a window and placed on the east side of the plot.

The monument’s north face, now difficult to read, is inscribed with the text of Ledyard’s original headstone. After the dedication of the 1854 monument, that stone was enclosed in a granite marker with a window and placed on the east side of the plot.

Cannons can be seen on the four corners of the monument, as well as in the posts of the iron fence surrounding the Ledyard plot.

Tags: Groton

Local residents killed and wounded during the American Revolution’s Battle of Groton Heights are honored with a large granite obelisk near the site of Fort Griswold.

Local residents killed and wounded during the American Revolution’s Battle of Groton Heights are honored with a large granite obelisk near the site of Fort Griswold.

The Groton Battle Monument, dedicated in 1830, honors the more than 80 men killed defending the fort during a British raid on September 6, 1781.

A dedication above the entrance on the west side of the monument reads, “The monument was erected under the patronage of the State of Connecticut, A.D. 1830, and in the 55th year of the independence of the U.S.A., in memory of the brave patriots who fell in the massacre at Fort Griswold, near this spot, on the 6th of Sept. A.D. 1781, when the British, under the command of the traitor, Benedict Arnold, burnt the towns of New London and Groton, and spread desolation and woe throughout this region.”

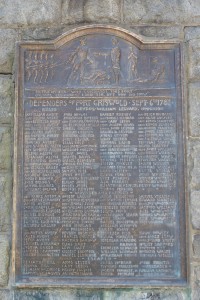

The dedication plaque inside the monument’s entranceway list the names of American defenders killed during the battle. The marker was originally part of the monument’s south face, facing the fort, but was moved to protect it from the elements.

The dedication plaque inside the monument’s entranceway list the names of American defenders killed during the battle. The marker was originally part of the monument’s south face, facing the fort, but was moved to protect it from the elements.

A large cannon near the monument’s west face was captured from a Spanish warship during the Spanish-American war.

A small museum next to the monument, closed during our visit, has displays about the history of the monument and the battle.

An undated monument erected by the city of Groton honors all local war veterans.

Fort Griswold

Across the street from the monument, the site of the former Fort Griswold has been turned into a state park. A memorial gateway, dedicated during the park’s opening on September 6, 1911 (the 130th anniversary of the battle), lists the 165 men who attempted to defend the fort against approximately 800 British troops during the battle.

Across the street from the monument, the site of the former Fort Griswold has been turned into a state park. A memorial gateway, dedicated during the park’s opening on September 6, 1911 (the 130th anniversary of the battle), lists the 165 men who attempted to defend the fort against approximately 800 British troops during the battle.

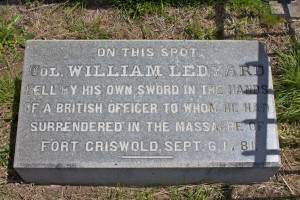

In the fort’s central courtyard, a small stone monument marks the spot where Col. William Ledyard was killed as he attempted to surrender the fort. After Ledyard was killed, British troops reportedly began massacring the Americans, with many wounded troops further being stabbed or shot before British officers stopped the fighting. (Ledyard is honored with a monument in a nearby cemetery that bears his name.)

A monument near the south end of the courtyard indicates where British Maj. William Montgomery was killed leading a bayonet assault against the fort.

A monument near the south end of the courtyard indicates where British Maj. William Montgomery was killed leading a bayonet assault against the fort.

During the battle, British troops guided by Norwich native and traitor Benedict Arnold invaded New London harbor. The city had served as an important supply base, and privateers operating out of New London had captured a number of British merchant ships.

More than 140 homes and buildings in downtown London were burned by the British invaded invaders, as were 19 homes on the Groton side of the harbor.

Next to the Groton Battle Monument, a 1916 monument honors Groton’s Civil War veterans.

Next to the Groton Battle Monument, a 1916 monument honors Groton’s Civil War veterans.

Tags: Groton

American Revolution General Israel Putnam is honored with a statue in Hartford’s Bushnell Park.

American Revolution General Israel Putnam is honored with a statue in Hartford’s Bushnell Park.

The Putnam statue, practically in the shadow of the state capitol building, was dedicated in 1874. The general is depicted, in uniform, cradling a sword in his left hand. Putnam is holding a three-cornered hat in his right hand.

The monument’s granite base bears a simple inscription on its front (east) side reading, “Israel Putnam.”

Putnam, a native of Danvers, Mass., led Connecticut troops during the Battle of Bunker Hill and may have issued the famous “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” command.

The west side of the base reflects the posthumous donation of the statue by Joseph Pratt Allyn, a Hartford native and a justice on the Supreme Court of the Arizona territory. Ally, who used the pen name “Putnam” when commenting on political events in letters to a Hartford newspaper, left money for the memorial.

The west side of the base reflects the posthumous donation of the statue by Joseph Pratt Allyn, a Hartford native and a justice on the Supreme Court of the Arizona territory. Ally, who used the pen name “Putnam” when commenting on political events in letters to a Hartford newspaper, left money for the memorial.

The monument was created by sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward, whose other works include the 7th Regiment Monument in New York’s Central Park.

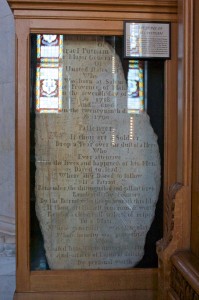

Not far from the Bushnell Park monument, Putnam’s original headstone has been placed in a case in the Hall of Flags at the Capitol building’s west entrance.

After his death in 1790, Putnam was placed in an aboveground tomb in Brooklyn. Over the years, souvenir hunters damaged the headstone, and the gravesite was deemed unsuitable for Putnam.

Putnam was moved to a new sarcophagus and monument on Canterbury Road (Route 169) in Brooklyn, and the original headstone was placed on display in the Capitol.

Putnam was moved to a new sarcophagus and monument on Canterbury Road (Route 169) in Brooklyn, and the original headstone was placed on display in the Capitol.

Putnam is also honored with memorials at Putnam Park in Redding and a Greenwich hill where he escaped from pursuing British forces.

Tags: Hartford

West Hartford honors its Civil War veterans with a simple memorial in the town’s North Cemetery.

West Hartford honors its Civil War veterans with a simple memorial in the town’s North Cemetery.

The Civil War monument, near the cemetery’s central driveway, resembles a large-scale version of the traditional Union veteran headstone shape. (In contrast to the rounded top seen on Union headstones, Confederate stones usually have a pointed top.)

The West Hartford monument bears a dedication on its west face reading, “Erected 1904 by the State of Connecticut in memory of the men of West Hartford who offered up their lives, a sacrifice in the Civil War, 1861-1865, and whose bodies were never brought home for burial.”

Under the dedication, the monument lists the names, regimental affiliations, and dates and places of death for 10 West Hartford residents lost in the war.

Under the dedication, the monument lists the names, regimental affiliations, and dates and places of death for 10 West Hartford residents lost in the war.

The monument’s east face lists an additional name, as well as an excerpt from the Bivouac of the Dead poem seen in several national cemeteries and war memorials.

The monument was supplied by the Stephen Maslen Company, which also supplied Civil War monuments in Suffield and Canton.

Tags: West Hartford

Samuel Colt is honored with a memorial statue in a park on the grounds of his former estate.

Samuel Colt is honored with a memorial statue in a park on the grounds of his former estate.

The Samuel Colt monument, near the Wethersfield Avenue entrance to Colt Park, was commissioned by Colt’s wife Elizabeth and dedicated in 1906 to honor the industrialist.

The monument depicts Colt at two stages in his life. The smaller statue, near the front of the monument, depicts a young Colt whittling a revolver chamber while serving as a sailor. The larger figure, standing atop the monument, depicts Colt as a successful manufacturer.

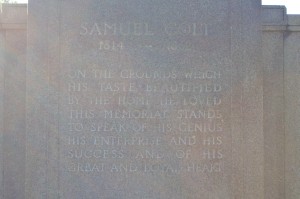

A dedication on the center panel of the monument’s west face reads, “Samuel Colt 1814-1862. On the grounds on which his taste beautified by the home he loved, this memorial stands to speak of his genius, his enterprise, and of his great and loyal heart.”

A dedication on the center panel of the monument’s west face reads, “Samuel Colt 1814-1862. On the grounds on which his taste beautified by the home he loved, this memorial stands to speak of his genius, his enterprise, and of his great and loyal heart.”

The monument also features two bronze panels illustrating scenes from Colt’s life. In the panel on the left, Colt is pictured meeting with the Russian Tsar, but the plaque’s staining make it tough to identify Colt or to figure out what’s going on.

In the right, panel, Colt is seen demonstrating a revolver to the British House of Commons. That plaque is also stained and faded, but you can see Colt holding a gun.

The monument was created by sculptor John Massey Rhind, whose works include the allegorical figures outside the New Haven County Courthouse.

The monument was created by sculptor John Massey Rhind, whose works include the allegorical figures outside the New Haven County Courthouse.

After Colt’s death, Elizabeth ran the manufacturing business until she sold it in 1901. In addition to donating the family estate as a park after her 1905 death, she also sponsored the construction of Hartford’s Church of the Good Shepherd and a building at the Wadsworth Atheneum.

Tags: Hartford