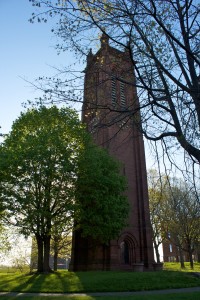

Hartford’s Keney Memorial Clock Tower and the small park surrounding it were donated by the Keney brothers in the late 19th century to honor their mother.

Hartford’s Keney Memorial Clock Tower and the small park surrounding it were donated by the Keney brothers in the late 19th century to honor their mother.

The tower, 130 feet tall, stands near the intersection of Albany Avenue with Main and Ely streets.

The tower was dedicated in 1898 to honor Rebecca Turner Keney, the mother of Walter and Henry Keney. The brothers ran the family’s wholesale grocery business, which, along with the family home, stood on the site of the tower.

Walter Keney died in 1889, and Henry died in 1894. In Henry’s will, money was set aside for Keney Park, to benefit a number of Hartford charities and to build the memorial tower.

According to the tower’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a dedication plaque inside the tower’s interior reads, “This tower, erected to the memory of my mother, is designed to preserve from other occupancy the ground sacred to me as her home and to stand in perpetual honor to the wisdom, goodness and womanly nobility of her to whose guidance I owe my success in life and its chief joy – Henry Keney.”

According to the tower’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a dedication plaque inside the tower’s interior reads, “This tower, erected to the memory of my mother, is designed to preserve from other occupancy the ground sacred to me as her home and to stand in perpetual honor to the wisdom, goodness and womanly nobility of her to whose guidance I owe my success in life and its chief joy – Henry Keney.”

The tower was designed by architect Charles C. Haight, whose other works include a number of buildings on Yale’s Old Campus.

The neighborhood surrounding the tower has changed considerably over the year. In the black-and-white image of the tower, taken around 1905, you can see homes on the other side of Ely Street.

In the background of the black-and-white image of the gate, a commercial building stood on Ely Street, on a now-vacant lot.

By the early 1990s, the park surrounding the tower was overgrown and the tower had been sprayed with graffiti. A restoration by the City of Hartford included replacing gold leaf on the clock face, site improvements and the installation of computerized chimes in the tower.

Tags: Hartford

The service of the 14th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, at Gettysburg is honored with several monuments on the battlefield.

The service of the 14th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, at Gettysburg is honored with several monuments on the battlefield.

The most prominent of the monuments honoring the regiment stands on Hancock Avenue, not far from the Angle, and marks the position from which the 14th helped repel Pickett’s Charge on the climactic third day of the battle.

The front (east) face of the monument, dedicated in 1884, features a bronze plaque describing the regiment’s Civil War service and major battles, including Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and several others before Appomattox.

The monument’s east face bears the simple inscription, “14 Conn.,” and the monument is topped with the Second Corps’ trefoil emblem.

The monument’s north face indicates the regiment’s affiliation in the Third Division, and the south face lists the division’s Second Brigade.

The west face of the monument features a plaque with a detailed description of the 14th’s actions during the battle of Gettysburg. The plaque reads, “The 14th C.V. reached the vicinity of Gettysburg at evening July 1st, 1863, and held this position July 2nd, 3rd and 4th.

“The regiment took part in the repulse of Longstreet’s grand charge on the 3rd, capturing in their immediate front more than 200 prisoners and five battle flags. They also, on the 3rd, captured from the enemy sharpshooters the Bliss buildings in their far front, and held them until ordered to burn them. Men in action, 160. Killed and wounded, 62.”

Bliss Barn

Bliss Barn

As the Hancock Avenue monument indicates, the 14th was involved in heavy fighting to capture the William Bliss farm buildings from Confederate sharpshooters harassing the Union line.

The Bliss barn stood about four-tenths of a mile west of the 14th’s position on Cemetery Ridge, in the no-man’s land between the Army of the Potomac and the main Confederate line on Seminary Ridge.

The barn and the nearby house changed hands between Union and Confederate forces several times on July 2. The 12th New Jersey and 1st Delaware had been able to capture the farm, but its exposed position and vulnerability to skirmish and artillery attacks made holding it very difficult.

On the morning of July 3, the 12th N.J. recaptured the barn, but was forced to withdraw. The 14th Connecticut was sent back to the farm, but soon found themselves outnumbered and under attack again.

On the morning of July 3, the 12th N.J. recaptured the barn, but was forced to withdraw. The 14th Connecticut was sent back to the farm, but soon found themselves outnumbered and under attack again.

To resolve the struggle for the Bliss buildings, orders were sent to the 14th CT to burn the barn and house. After doing so, the 14th withdrew to the Union line along Cemetery Ridge.

The 14th’s contributions to the capture and destruction of the Bliss farm are marked with several monuments at the site. The former center of the barn is marked with a granite monument bearing, on its east face, the 2nd Corps trefoil and a brief summary of the burning of the Bliss buildings.

The west face of the monument, which stands in front of a mound that led to the barn’s second story, is inscribed “14 C.V.”

The west face of the monument, which stands in front of a mound that led to the barn’s second story, is inscribed “14 C.V.”

A short walk to the north, a smaller marker indicates the center of the Bliss house. The monument also explains the house was captured and burned by the 14th on July 3.

A monument to the 12th New Jersey stands between the two Connecticut monuments, and a monument honoring the 1st Delaware stands north of the former house site.

An acre surrounding the former barn and house was purchased by surviving members of the 14th Regiment in 1885, and that purchase is marked by four small boundary markers (similar to the battlefield’s flank markers) that remain on the site today.

The regiment, recruited primarily from central CT, mustered into service August 23, 1862, with 1,015 men. Less than three weeks later, the barely trained regiment found itself in intense fighting at Antietam’s Bloody Lane. During the war, the regiment fought in 34 engagements between Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s 1865 surrender at Appomattox.

The regiment, recruited primarily from central CT, mustered into service August 23, 1862, with 1,015 men. Less than three weeks later, the barely trained regiment found itself in intense fighting at Antietam’s Bloody Lane. During the war, the regiment fought in 34 engagements between Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s 1865 surrender at Appomattox.

Tags: Gettysburg

The service of the 2nd Connecticut Light Artillery at Gettysburg is honored with a monument on Hancock Avenue.

The service of the 2nd Connecticut Light Artillery at Gettysburg is honored with a monument on Hancock Avenue.

The monument, dedicated on July 3, 1888, marks the regiment’s position near the left end of the Union line during the Confederate charge toward Cemetery Ridge that ended the battle on July 3, 1863.

The monument’s east face bears the state seal and the inscription, “2d Conn, Light Battery. The east face also bears a star emblem and the inscription, “Artillery Reserve.”

The north face displays crossed cannons and the year, 1863.

The west face bears a dedication reading, “Tribute from the State of Conn.”, as well as a brief regimental history: “Mustered in Sept. 10, 1862. Mustered out Aug. 10, 1865. Engagements: Gettysburg, Fort Morgan (Alabama), Fort Gaines (Alabama), Blakeley (Fort Blakeley, Alabama).”

The west face bears a dedication reading, “Tribute from the State of Conn.”, as well as a brief regimental history: “Mustered in Sept. 10, 1862. Mustered out Aug. 10, 1865. Engagements: Gettysburg, Fort Morgan (Alabama), Fort Gaines (Alabama), Blakeley (Fort Blakeley, Alabama).”

The south face displays crossed ram staffs and cannonballs, as well as the 1888 dedication year.

The 2nd Connecticut Light Artillery was formed in Bridgeport, and the 115 members of the unit trained at Seaside Park until marching to New York in October for a train to Washington.

They served in the capitol’s defenses before fighting at Gettysburg, where they occupied their position for 56 hours. The regiment’s only casualties were three horses.

They served in the capitol’s defenses before fighting at Gettysburg, where they occupied their position for 56 hours. The regiment’s only casualties were three horses.

After Gettysburg, the unit served in Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, and Florida before finishing the war in Alabama. They were ordered to return home in July of 1865 and sailed to New Haven before mustering out in August of 1865.

Tags: Gettysburg

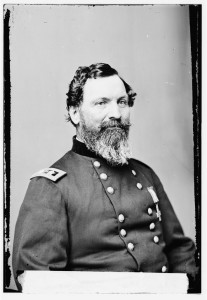

Connecticut native and Sixth Corps commander Maj. General John Sedgwick is honored with an equestrian monument at Gettysburg.

Connecticut native and Sixth Corps commander Maj. General John Sedgwick is honored with an equestrian monument at Gettysburg.

The monument to Sedgwick, born in Cornwall Hollow, is on Gettysburg’s Sedgwick Avenue, just north of the intersection with Wheatfield Road.

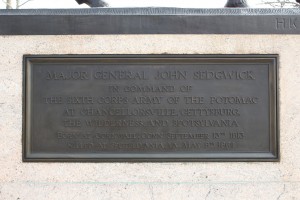

The monument, dedicated in 1913, depicts Sedgwick (and his horse) looking west toward the battlefield. A dedication on the north side of the monument’s base reads, “Major General John Sedgwick. In command of the Sixth Corps, Army of the Potomac, at Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania. Born at Cornwall, Conn., September 13th 1813. Killed at Spotsylvania, Va., May 9th 1864.”

The west face bears a bronze Connecticut seal, and the south face bears a dedication reading, “Erected by the State of Connecticut in grateful memory of the service given to the nation by her honored son John Sedgwick. Loyal citizen, illustrious soldier, beloved commander.”

The west face bears a bronze Connecticut seal, and the south face bears a dedication reading, “Erected by the State of Connecticut in grateful memory of the service given to the nation by her honored son John Sedgwick. Loyal citizen, illustrious soldier, beloved commander.”

The monument was created by Henry K. Bush-Brown, who was also responsible for the George Meade and John Reynolds equestrian monuments at Gettysburg.

Sedgwick, a career army officer, served in the Mexican-American War as well as on the Western Frontier. He was severely wounded at Antietam, but returned to take command of the Sixth Corps.

Sedgwick was killed during the Battle of Spotsylvania in 1864. While rallying his troops, he claimed they were beyond the range of Confederate snipers moments before he was mortally wounded.

Sedgwick was killed during the Battle of Spotsylvania in 1864. While rallying his troops, he claimed they were beyond the range of Confederate snipers moments before he was mortally wounded.

Sedgwick was buried in his native Cornwall Hollow, and is honored there with a monument across Cornwall Hollow Road (Route 43) from his grave.

During the Battle of Gettysburg, the Sixth Corps arrived on the field late on July 2 after a march of more than 30 miles during the day and night of July 1. The corps assisted the Fifth Corps in repelling Confederate attacks. The next day, the Fifth was held in reserve, with portions being deployed in various sections of the Union line. At one point, different units under Sedgwick’s command were psoted on the far right and left flanks.

Tags: Gettysburg

The 27th Connecticut Regiment is honored with a collection of monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield.

The 27th Connecticut Regiment is honored with a collection of monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield.

Perhaps the regiment’s most prominent monument marks the spot where the unit’s commander, Lt. Col Henry Merwin, was killed during heavy fighting in Rose’s Wheatfield.

The monument, a granite obelisk topped with an eagle, was dedicated in October of 1885. The monument’s front (north) face feature’s the regiment’s name, the Second Corps trefoil, the 1885 erection date, and the July 2, 1863 date of the Wheatfield fighting.

An inscription within a shield on the north face provides a detailed account of the unit’s actions on July 2, and highlights the death of Merwin and Capt. Jedidiah Chapman (the location of Chapman’s death is marked with a monument we’ll describe shortly).

An inscription within a shield on the north face provides a detailed account of the unit’s actions on July 2, and highlights the death of Merwin and Capt. Jedidiah Chapman (the location of Chapman’s death is marked with a monument we’ll describe shortly).

The monument’s south face bears an inscribed Connecticut seal.

Late in the afternoon of July 2, the 27th participated in a charge westward across the Wheatfield toward Rose’s Woods and Stony Hill. The attack succeeded in repulsing Confederates, who would later counterattack and eventually recapture the Wheatfield (which changed hands several times on the second day of the battle).

The 27th is honored with a second monument on Brooke Avenue, not far from the spot of their western advance during their afternoon charge. The monument, which features the peaked-top design used by several other Connecticut monuments at Gettysburg, was dedicated

The 27th is honored with a second monument on Brooke Avenue, not far from the spot of their western advance during their afternoon charge. The monument, which features the peaked-top design used by several other Connecticut monuments at Gettysburg, was dedicated on the same day in October 1885 as the Wheatfield monument in 1889.

The front (west) side of the monument lists the unit’s affiliations (4th Brigade, 1st Division, 2nd Corps) and “advanced position of this regiment in the brigade charge, July 2nd, 1863.”

The west side also features a Connecticut seal as well as the Second Corps trefoil.

The monument’s south face displays crossed muskets.

The monument’s south face displays crossed muskets.

The monument’s east side is inscribed with a dedication reading, “Erected by the Commonwealth of Connecticut as a memorial to the valor of her loyal sons.” The description of Connecticut as a commonwealth is an unfortunate error since Connecticut is formally designated as a state (although there’s no practical difference).

A short distance east of the Brooke Avenue monument, a small marker on a boulder was dedicated in 1885 to designate the regiment’s advanced position within the woods.

Officer Memorials

The deaths of Col. Merwin and Capt. Chapman are honored with separate markers on the battlefield. The Merwin memorial is on the side Wheatfield Road, a short distance from the regiment’s Wheatfield monument.

The deaths of Col. Merwin and Capt. Chapman are honored with separate markers on the battlefield. The Merwin memorial is on the side Wheatfield Road, a short distance from the regiment’s Wheatfield monument.

Merwin, a Brookfield native, was active in New Haven business when the war broke out. He served with the 2nd Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, a regiment that enlisted for three months, in 1861. When another call for volunteers was issued in 1862, Merwin enlisted again.

Chapman, a New Haven native, is honored with a small marker along de Trobriand Avenue. The marker was originally placed near the Merwin marker on Wheatfield Road because correct location was privately owned, but was moved after that land was purchased by the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association.

The 27th, recruited primarily from New Haven county, was formed in September 1862 for a nine-month enlistment. After fighting at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, the regiment mustered out near the end of July 1863.

The 27th, recruited primarily from New Haven county, was formed in September 1862 for a nine-month enlistment. After fighting at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, the regiment mustered out near the end of July 1863.

At Gettysburg, the regiment engaged 160 and had 37 casualties (10 killed, 23 wounded and four missing).

Tags: Gettysburg

The monument honoring the 20th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment’s service during the Battle of Gettysburg stands near the southern end of Culp’s Hill.

The monument honoring the 20th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment’s service during the Battle of Gettysburg stands near the southern end of Culp’s Hill.

The monument, dedicated in 1885, was placed on the regiment’s battle line during the mornings of the battle’s second and third day. The monument was oriented east to face the woods toward enemy lines, so visitor to today’s Slocum Avenue see the rear face first.

The monument’s front (east) face bears the simple inscription, “20th Conn. Vols.” along with a state seal and the 12th Corps’ star. The north face lists the unit’s casualties in Gettysburg as well as the rest of the war.

At Gettysburg, the regiment had five members killed, 22 wounded and 1 reported missing.

At Gettysburg, the regiment had five members killed, 22 wounded and 1 reported missing.

The monument’s west face bears a detailed description of its action at Gettysburg, and the south face lists the regiment’s 14 engagements during the Civil War.

The 20th was recruited primarily from New Haven and Hartford county residents, and was organized in New Haven in September of 1862. It served in the Virginia in 1862 and 1863, including the Battle of Chancellorsville in May of 1863.

The regiment arrived in Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, and was placed along the right flank of the Army of the Potomac. After building defensive earthworks, the regiment was later shifted to the woods of Little Round Top to support fighting along the army’s left flank.

The regiment arrived in Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, and was placed along the right flank of the Army of the Potomac. After building defensive earthworks, the regiment was later shifted to the woods of Little Round Top to support fighting along the army’s left flank.

When they returned to Culp’s Hill that night, they found their earthworks had been taken by Confederate forces.

The next morning, the 20th helped repulse Confederate attacks on Culp’s Hill, and helped direct Union artillery fire. Unfortunately for the 20th, this required close proximity to the enemy and exposed the regiment to poorly targeted or misfiring shells.

At least one member of the regiment was struck by friendly fire, with Private George Warner of Bethany losing both arms after being hit by a Union artillery shell.

At least one member of the regiment was struck by friendly fire, with Private George Warner of Bethany losing both arms after being hit by a Union artillery shell.

During the monument’s 1885 dedication ceremonies, Warner removed the flag that covered the monument before its dedication. Pulleys were placed in a nearby tree and a rope was tied around Warner’s waist. As Warner walked backwards away from the monument, the flag was lifted from the new monument.

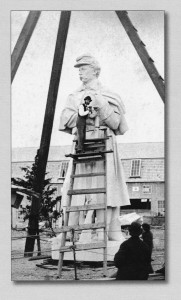

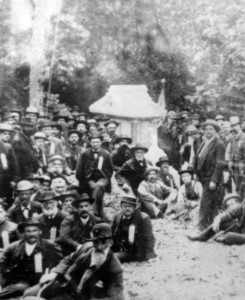

In the black-and-white image of the dedication ceremony, which came from our friends at The Gettysburg Daily, Warner can be seen sitting on a large boulder near the center of the image. That boulder, just northeast of the monument, is known today as the Warner Rock.

The 20th CT monument is a short walk from a monument honoring the 5th CT Regiment. In the wide view of Slocum Avenue at the bottom of this post, the 20th monument is on the left. The monument in the middle honors the 3rd Maryland Infantry (U.S.), and the 5th Regiment’s monument is on the right.

Tags: Gettysburg

The service of the 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Battle of Gettysburg is honored with a pair of monuments and a memorial flagpole.

The service of the 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Battle of Gettysburg is honored with a pair of monuments and a memorial flagpole.

The first of the two monuments honoring the regiment stands in today’s Barlow Knoll, where significant fighting took part on July 1, 1863, the first day of the battle.

The monument, erected in 1884, features a dedication on its north side reading, “Erected by the survivors of the 17th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, 11th Corps, in memory of their gallant comrades who fell here on the 1st day and on this battlefield on the 2nd and 3rd days of July, 1863.”

The base of the north side also bears the regiment’s name.

The base of the north side also bears the regiment’s name.

The west side of the monument lists 10 members of the regiment killed at Gettysburg. The south face lists 16 members killed, and also features raised Connecticut and United States shields. The east face lists 9 men killed in the battle.

The 17th, part of the Union Army’s 11th Corps, was ordered into action near the front right flank of the Union line. The regiment’s position on the knoll, later named after Brigadier General Francis Barlow of New York, was overrun by Confederate forces and the regiment was forced to retire to East Cemetery Hill.

Near the monument, a flagpole erected by the regimental survivors in 1885 honors Lt. Col. Douglas Fowler of Guilford. Fowler, leading the unit on horseback, was killed when he was struck by an artillery shell. Fowler’s body was not identified after the battle, and it’s likely that he was buried in the Unknown section of the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

Near the monument, a flagpole erected by the regimental survivors in 1885 honors Lt. Col. Douglas Fowler of Guilford. Fowler, leading the unit on horseback, was killed when he was struck by an artillery shell. Fowler’s body was not identified after the battle, and it’s likely that he was buried in the Unknown section of the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

(The monument near the flagpole, featuring the gentleman blowing a bugle, honors the 153rd Pennsylvania regiment.)

After the retreat, the 17th was posted on the eastern side of East Cemetery Hill, and over the next two days, the regiment helped repulse several Confederate attacks.

After the retreat, the 17th was posted on the eastern side of East Cemetery Hill, and over the next two days, the regiment helped repulse several Confederate attacks.

Its service at that side of the battlefield is honored with a granite obelisk, dedicated in 1889, along today’s Wainwright Avenue.

A dedication on the monument’s south face reads, “This memorial is erected by the State of Connecticut to honor her brave sons.” The west face recounts the regiment’s action during the battle.

The monument repeats the Connecticut and U.S. shields on its east face, and its north face lists the unit’s membership in the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, 11th Corps.

Tags: Gettysburg

The 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment’s service at Gettysburg is honored with a monument near the southern end of Culp’s Hill.

The 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment’s service at Gettysburg is honored with a monument near the southern end of Culp’s Hill.

The granite monument, along Slocum Avenue, was dedicated in August of 1887. The front (west) face of the monument is inscribed with a simple dedication reading, “5th Conn. Infantry, July 2 & 3, 1863.” The west face also has the name of the 12th Corps inscribed, as well as the corps’ star emblem. The base is inscribed with the unit’s affiliation with the 1st Brigade and 1st Division within the 12th Corps.

The monument’s other faces are free of inscriptions or decoration.

The 5th Regiment, one of the earlier Connecticut regiments, was mustered into service in July of 1861 and included recruits from most of the state’s cities and towns. The unit had a total of 1,754 recruits, and its casualties included 81 killed, 2 missing, 254 wounded, and 201 captured.

The 5th Regiment, one of the earlier Connecticut regiments, was mustered into service in July of 1861 and included recruits from most of the state’s cities and towns. The unit had a total of 1,754 recruits, and its casualties included 81 killed, 2 missing, 254 wounded, and 201 captured.

At Gettysburg, the regiment arrived late in the evening of July 1, and helped build earthworks on Culp’s Hill the next morning. After being ordered to support 3rd Corps forces on July 2, the unit later found their original earthworks occupied by Confederates.

The unit fought in the defense of Culp’s Hill and supported Union cavalry forces on July 3, 1863.

The 5th was one of several regiments that trained along Campfield Avenue in Hartford, near today’s Barry Square, before heading south to fight.

The 5th was one of several regiments that trained along Campfield Avenue in Hartford, near today’s Barry Square, before heading south to fight.

Tags: Gettysburg

The Antietam National Cemetery is the final resting place of nearly 4,800 Union Civil War veterans as well as more than 200 veterans of other wars.

The Antietam National Cemetery is the final resting place of nearly 4,800 Union Civil War veterans as well as more than 200 veterans of other wars.

The cemetery, on Route 34 in Sharpsburg, was dedicated on Sept. 17, 1867, the fifth anniversary of the Battle of Antietam. The land chosen for the cemetery site, which stands west of the battlefield, was occupied by Confederate artillery during the battle.

The cemetery is dominated by a 45-foot-high monument depicting a Union soldier at rest. Formally known as the Private Soldier of the Civil War, the figure also bears the local nickname “Old Simon.”

A dedication on the front (north) face of the monument’s base reads, “Not for themselves but for their country.” The north face also bears the date of the battle and a carved trophy with crossed flags, swords and other military accoutrements.

A dedication on the front (north) face of the monument’s base reads, “Not for themselves but for their country.” The north face also bears the date of the battle and a carved trophy with crossed flags, swords and other military accoutrements.

The cemetery holds 4,776 Union remains from Antietam and other Civil War battles in Maryland, as well as more than 200 veterans from the Spanish-American War, the World Wars and Korea. Among the Civil War heroes, more than 1,800 could not be identified.

The Connecticut section, on the east side of the cemetery, has 82 graves of soldiers that were identified.

After the battle, the dead were buried hastily on the battlefield or near buildings that had served as hospitals. In 1866 and 1867, remains were recovered and prepared for reburial in the national cemetery (many veterans from Maryland and Pennsylvania were claimed by their families for burial in their hometowns).

After the battle, the dead were buried hastily on the battlefield or near buildings that had served as hospitals. In 1866 and 1867, remains were recovered and prepared for reburial in the national cemetery (many veterans from Maryland and Pennsylvania were claimed by their families for burial in their hometowns).

The Private Soldier monument, which was dedicated in the cemetery in 1880, was designed by Hartford monument dealer James Batterson, whose firm supplied a number of Civil War memorials in Connecticut.

The design is believed to be among the first depictions of a standing soldier as part of a Civil War monument. The monument was carved by sculptor James Poletto (pictured below working on the monument) of Westerly, Rhode Island.

The monument was created in several sections, and the upper half of the soldier figure spent several months in the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., after falling from a barge.

The monument was created in several sections, and the upper half of the soldier figure spent several months in the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., after falling from a barge.

Tags: Antietam

The brand-new, barely trained 16th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment suffered heavy losses during its first action at Antietam.

The brand-new, barely trained 16th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment suffered heavy losses during its first action at Antietam.

The regiment’s service is honored with a multi-colored granite obelisk, dedicated in 1894, on the western edge of the 40-Acre Cornfield off Antietam’s Branch Avenue.

The monument’s west face bears a dedication reading, “Position of the 16th Conn. Vol. Infantry 5 p.m., Sept. 17, 1862.”

The west face also bears a bronze plaque depicting a scene from the battle. The plaque is a 1998 reproduction sponsored by the reenactment and preservation group Company G, 14th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865.

The monument’s south face lists the regiment’s casualty total from Antietam. Out of the 779 engaged, 43 were killed and 161 were wounded (for a total of 204 casualties, or 26 percent of the regiment’s roster). The south face also bears an engraved Hartford seal, reflecting the unit’s recruitment in that city.

The monument’s south face lists the regiment’s casualty total from Antietam. Out of the 779 engaged, 43 were killed and 161 were wounded (for a total of 204 casualties, or 26 percent of the regiment’s roster). The south face also bears an engraved Hartford seal, reflecting the unit’s recruitment in that city.

The east face bears an engraved Connecticut seal and lists the unit’s affiliations: 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 9th Army Corps.

The north face lists the monument’s erection by the State of Connecticut in 1894 and displays an engraved trophy with a cannon and an anchor.

The monument is best approached as a stop along the park’s Final Attack Trail.

During the battle, the regiment was, along with the 4th Rhode Island, posted on the left flank of the 9th Corp units advancing west from the Burnside Bridge area. The regiment suffered heavy losses on the flank when it was hit by a Confederate counterattack late in the afternoon.

During the battle, the regiment was, along with the 4th Rhode Island, posted on the left flank of the 9th Corp units advancing west from the Burnside Bridge area. The regiment suffered heavy losses on the flank when it was hit by a Confederate counterattack late in the afternoon.

The 16th Regiment mustered into service in late August of 1862 and, like their counterparts in the 14th Regiment, saw their first action at Antietam. The unit had received almost no training before arriving at Antietam, and had loaded their weapons for the first time only the previous day.

The regiment would serve through the remainder of the war, and would have a large number of members held in the Andersonville prisoner of war camp after an 1864 battle in Plymouth, North Carolina.

Tags: Antietam