The first Union general killed in the Civil War is one of several veterans buried in Eastford’s General Lyon Cemetery.

The first Union general killed in the Civil War is one of several veterans buried in Eastford’s General Lyon Cemetery.

Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, an Eastford native and West Point graduate, was killed in August of 1861 while fighting in Missouri.

Lyon is honored with a marble monument near the middle of the small cemetery, which was founded in 1805 and is located on today’s General Lyon Road.

The front (east) face of the marble monument features a carved portrait of Lyon leading troops on horseback and the simple inscription, “Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, U.S.A.”

The east face also bears an elaborate trophy featuring the United States shield and crossed swords and cannon, and the shaft is topped with a marble eagle.

The east face also bears an elaborate trophy featuring the United States shield and crossed swords and cannon, and the shaft is topped with a marble eagle.

The north face lists Lyon’s birthday (July 14, 1818) as well as his death during the battle of Wilson’s Creek (Missouri) on August 10, 1861.

The west face is inscribed with the Capture of Camp Jackson on May 10, 1861, the battle of Booneville on June 16, and the battle of Dug Springs on August 1.

The south face lists seven battles during the Mexican-American War in which Lyon fought.

In the early stages of the war, Lyon captured arms as well as a group pro-Confederacy militia members who had gathered in St. Louis at “Camp Jackson,” named after Missouri’s secessionist governor.

Lyon’s body was hidden after the battle and his remains laid in state in St. Louis, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, New York and Hartford before he was buried in Eastford. The 1874 book The American Historical Record describes the erection of the Eastford monument.

Lyon’s body was hidden after the battle and his remains laid in state in St. Louis, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, New York and Hartford before he was buried in Eastford. The 1874 book The American Historical Record describes the erection of the Eastford monument.

The Lyon family plot also features a small cannon near the front, and two cannons have been buried at the front corners of the retaining wall surrounding the plot.

The cemetery also includes the graves of numerous other Civil War veterans, including several members of the Lyon family.

Tags: Eastford

The Town of Union honors its Civil War veterans and their mothers with a monument on the town green.

The Town of Union honors its Civil War veterans and their mothers with a monument on the town green.

The monument, dedicated in 1902, features a cannon (which may be a replica) resting on a concrete base. A small cannonball pyramid rests in front of the monument.

A dedication on the southeast side of the monument’s base reads, “Dedicated in grateful memory to the mothers who gave their sons, to the soldiers who gave their lives, and to those who, daring to die, survived the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865.”

The expression of gratitude toward the soldiers’ mothers is uncommon, and perhaps unique among Civil War memorials.

The expression of gratitude toward the soldiers’ mothers is uncommon, and perhaps unique among Civil War memorials.

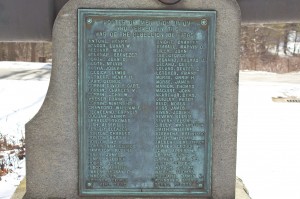

The northwest face of the monument bears a plaque listing 66 Union residents who served in the Civil War.

Somewhat unusually, the honor rolls lists John W. Corbin as well as his substitute, Frank Walker. Corbin had enlisted in the 22nd Regiment of the Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, but arranged for the substitute (who was also from Union) after his father became ill.

Corbin’s family donated the plaques, and Corbin presented the monument to the town during the dedication ceremonies.

The southwest face of the Union monument lists 10 members of the local GAR post, as well as the monument’s 1902 dedication date.

The southwest face of the Union monument lists 10 members of the local GAR post, as well as the monument’s 1902 dedication date.

If the cannon is real, its foundry markings are hidden under paint, and its barrel has been filled with concrete.

Behind the monument, a 1978 CT Historical Commission marker provides a brief introduction to the history of Union, which was incorporated in 1734 and was the last town in the state to be settled east of the Connecticut River.

Near the monument, a plaque marks the location of a time capsule scheduled to be opened on the town’s 250th anniversary in 2034.

The white building in front of the Civil War monument is the former Town Hall, which was built in 1847 and today serves as the home of the Union Historical Society.

The white building in front of the Civil War monument is the former Town Hall, which was built in 1847 and today serves as the home of the Union Historical Society.

The Town of Union web site has a rendering of a proposed veterans’ memorial that would stand between the Civil War monument and the Historical Society building.

Tags: Union

The first Civil War monument in Connecticut to display a figure stands on the green in Granby.

The first Civil War monument in Connecticut to display a figure stands on the green in Granby.

The brownstone Granby Soldiers’ Monument, dedicated in 1868, features contemplative bearded soldier holding a rifle while his overcoat is draped over his shoulders.

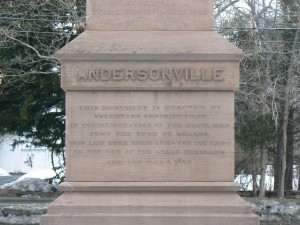

A dedication on the front (south) face reads, “This monument is erected by voluntary contributions in commemoration of the brave men from the town of Granby who laid down their lives for the Union in the War of the Great Rebellion. Erected July 4, 1868.”

The south face also lists the names of eight residents or natives killed in the war, and honors men who were held at the Confederate prisoner of war camp in Andersonville, Georgia.

An inscription on the south side of the monument’s base reads, “They shall hunger no more, neither thirst any more.”

An inscription on the south side of the monument’s base reads, “They shall hunger no more, neither thirst any more.”

The east face lists 12 names, the battle of Petersburg, Virginia, and bears an inscription reading, “Faithful unto death.”

The north face lists seven names, including three affiliated with Massachusetts regiments, and honors the Battle of Cold Harbor, Va. The base is inscribed, “Death is swallowed up in victory.”

The west face lists eight names, honors the Battle of Antietam by listing Sharpsburg (Maryland), the town where it was fought.

In front of the monument, a bronze plaque describes a 2002 restoration of the monument and lists eight additional names of Granby residents lost in the war.

Just south and east of the Civil War monument, a 1985 obelisk honors Granby’s World War II (11 residents lost), Korea and Vietnam (7 lost) veterans.

Just south and east of the Civil War monument, a 1985 obelisk honors Granby’s World War II (11 residents lost), Korea and Vietnam (7 lost) veterans.

The 1868 dedication data for the Civil War monument makes it among the first in the state, and it is the first Civil War monument in Connecticut to feature a figure. Earlier Civil War monuments in Kensington, Northfield, North Branford, Cheshire and other locations were obelisks.

The monument was supplied by James Batterson, a Hartford entrepreneur and monument dealer who provided many of the state’s Civil War memorials. On the Granby monument, Batterson listed himself as the sculptor, even though the actual carving was performed by staff sculptor Charles Conrads.

Batterson’s firm also provided a nearly identical 1867 monument in Deerfield, Mass.

Batterson’s firm also provided a nearly identical 1867 monument in Deerfield, Mass.

Tags: Granby

UPDATE: Scheduled for removal in July of 2020

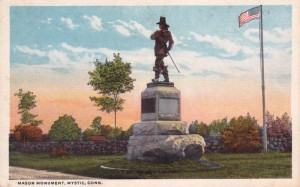

An 1889 monument to English settler John Mason illustrates how our attitudes toward historic people and events can change over time.

The monument, which stands today on Windsor’s Palisado Green, depicts Mason, in 17th century clothing, drawing a sword.

A dedication plaque on the west face of the monument’s base reads, “Major John Mason. Born 1600 in England. Immigrated to New England in 1630. A founder of Windsor, Old Saybrook and Norwich. Magistrate and Chief Military Officer of the Connecticut Colony, Deputy Governor and acting Governor. A Patentee of the Colonial Charter. Died 1672 in Norwich. Erected at Mystic in 1889 by the State of Connecticut, this monument was relocated in 1996 to respect a sacred site of the 1637 Pequot War.”

As the plaque indicates, the Mason monument was dedicated in 1889 on Pequot Avenue in the Mystic section of Groton. The monument was built to mark the site of a former Pequot settlement that Mason burned in 1637, and to honor Mason’s contributions to the defeat of the Pequots by English settlers.

As the plaque indicates, the Mason monument was dedicated in 1889 on Pequot Avenue in the Mystic section of Groton. The monument was built to mark the site of a former Pequot settlement that Mason burned in 1637, and to honor Mason’s contributions to the defeat of the Pequots by English settlers.

At the time, the monument bore a dedication reading, “Erected AD 1889 By the State of Connecticut to commemorate the heroic achievement of Major John Mason and his comrades, who near this spot in 1637, overthrew the Pequot Indians, and preserved the settlements from destruction.”

Estimates place the number of Pequots killed by Mason’s forces between 400 and 700. In July of 1637, a small group of Pequot warriors was defeated in Fairfield’s Great Swamp Fight, and fighting between the settlers and the natives came to a close.

In late 1992, local Pequots (who, thanks to the development of Foxwoods, had considerably more economic and political influence than they had when the monument was dedicated a century earlier) began efforts to have the Mason monument removed from the massacre site, which they considered sacred ground.

In late 1992, local Pequots (who, thanks to the development of Foxwoods, had considerably more economic and political influence than they had when the monument was dedicated a century earlier) began efforts to have the Mason monument removed from the massacre site, which they considered sacred ground.

After debate about the historic context of the monument’s original dedication and today’s differing views about Native Americans, the Mason monument was moved from Mystic to Windsor, and the dedication plaque was changed to reflect Mason’s political contributions to that town, Old Saybrook and Norwich.

The Mason statue was created by sculptor James C.G. Hamilton, whose other works included a Civil War monument in Muskegon, Michigan, and a bronze statue of Cleveland founder Moses Cleaveland.

Tags: Windsor

Windsor honors its war veterans with a large sculpted eagle on the town green.

Windsor honors its war veterans with a large sculpted eagle on the town green.

The Windsor War Memorial, dedicated in 1929, was created by noted sculptor and Windsor resident Evelyn Beatrice Longman.

The monument features a five-foot bronze eagle atop a stone cairn. The monument’s front (west) face includes a bronze wreath and a dedication “To the patriots of Windsor.”

The monument stands at the southern end of the town green on Broad Street (Route 159).

Scupltor Evelyn Beatrice Longman also created the Spirit of Victory monument in Hartford’s Bushnell Park (which honors Spanish-American War veterans) as well as the World War I monument in downtown Naugatuck.

Tags: Windsor

The Veterans’ Memorial in Farmington provides an unusually comprehensive tribute to local residents who participated in wars and skirmishes.

The Veterans’ Memorial in Farmington provides an unusually comprehensive tribute to local residents who participated in wars and skirmishes.

The 1992 monument, in front of Town Hall and near the intersection of Farmington Avenue (Route 4) and Monteith Drive, features five granite columns inscribed with the names of residents who died while serving the nation.

The monument’s front (northwest) face bears the simple inscription “Duty, Honor, Country” and five service branch emblems.

The monument’s columns also list military conflicts starting with early battles including the English settlers’ fights with the Pequots in the 1630s, the French and Indian Wars and the 1712 Defense of Litchfield.

More recent conflicts listed on the monuments include peacekeeping in Lebanon (1982-4), the Grenada invasion in 1983 and Operation Desert Storm in 1990-91).

More recent conflicts listed on the monuments include peacekeeping in Lebanon (1982-4), the Grenada invasion in 1983 and Operation Desert Storm in 1990-91).

Looking at major conflicts more typically cited on municipal war memorials, the Farmington monument lists the names of 11 residents killed or wounded in the American Revolution; 63 in the Civil War; eight in World War I; 18 in World War II; and five in Vietnam.

The monument’s southeast face repeats the service emblems, but is otherwise unlettered.

A tree in front of the Veterans’ Memorial is a descendent of Hartford’s Charter Oak.

Farmington’s Civil War, World War I, World War II and Vietnam heroes are also honored with monuments in the town’s Riverside Cemetery.

Farmington’s Civil War, World War I, World War II and Vietnam heroes are also honored with monuments in the town’s Riverside Cemetery.

Farmington honors its Civil War heroes with a brownstone obelisk in Riverside Cemetery.

Farmington honors its Civil War heroes with a brownstone obelisk in Riverside Cemetery.

The Soldiers’ Monument, erected in 1872, bears a dedication on its front (south) face reading, “To the memory of volunteer soldiers from this village.”

The south face also bears the names of five residents killed in the war, a decorative trophy featuring crossed rifles. The south face also honors the battle of Gettysburg, and the base includes the inscription, “They gave their lives for our country and freedom.”

The east face includes five names, and honors the battle of Antietam. The base includes an inscribed poem reading, “How sleep the brave who sink to rest, by all their country’s wishes blest.”

The north face lists five names, as does the west face. The west face also honors the battle of Fort Wagner (S.C.), and features a raised United States seal. The west base bears the inscription, “God, preserve the nation in peace.”

The north face lists five names, as does the west face. The west face also honors the battle of Fort Wagner (S.C.), and features a raised United States seal. The west base bears the inscription, “God, preserve the nation in peace.”

Information about the monument’s designer or supplier has not come to light. The lettering has faced in several placed, making it difficult to read, and the monument has large areas of lichen growth.

Directly across from the Soldiers’ Monument, a memorial honors Farmington residents killed in the World Wars, Korea and Vietnam. The undated memorial lists two residents killed in World War I, nine in World War II, one in Korea and two in Vietnam.

A short walk west of the war memorials is the grave of Foone, one of the former Amistad slaves. Foone’s grave is listed as a stop on the Connecticut Freedom Trail. A bronze plaque was placed in front of the grave in 2001 because the inscription was difficult to read.

A short walk west of the war memorials is the grave of Foone, one of the former Amistad slaves. Foone’s grave is listed as a stop on the Connecticut Freedom Trail. A bronze plaque was placed in front of the grave in 2001 because the inscription was difficult to read.

Farmington’s Civil War veterans are also honored with a 1916 monument in the Unionville section.

Tags: Farmington

Canton honors veterans of the Civil War and other conflicts with a 1903 monument in Village Cemetery.

Canton honors veterans of the Civil War and other conflicts with a 1903 monument in Village Cemetery.

The Veteran’s Memorial, in the Collinsville section of Canton, honors veterans of the American Revolution, War of 1812, Civil War and Spanish-American War and lists Civil War heroes whose bodies were not returned.

A dedication on the monument’s south face reads, “Erected 1903 by the State of Connecticut and the Collinsville Cemetery Association in memory of the men of Canton who offered up their lives [as] a sacrifice in the Civil War, 1861-1865, and whose bodies were never brought home.”

The south face also features an elaborate Connecticut state seal.

The north face features a bronze plaque listing 39 Canton residents who died during their Civil War service. Along with their names, the plaque lists their regimental affiliation, and the date and place of death.

The north face features a bronze plaque listing 39 Canton residents who died during their Civil War service. Along with their names, the plaque lists their regimental affiliation, and the date and place of death.

The monument was supplied by the Stephen Maslen Corp., a Hartford granite dealer whose other Connecticut projects included the Soldiers’ Monument in Suffield.

A flagpole stands near the monument, which is surrounded by smaller flags and flanked by shrubbery.

Tags: Canton, Collinsville

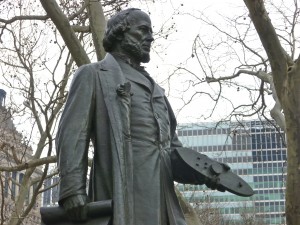

The designer of the Civil War ironclad ship the Monitor is honored with a statue in New York City’s Battery Park.

The designer of the Civil War ironclad ship the Monitor is honored with a statue in New York City’s Battery Park.

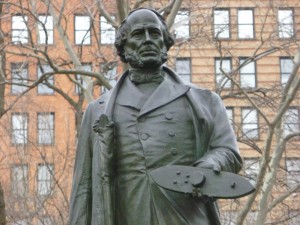

The 1903 John Ericsson Memorial honors the Swedish inventor who designed the Monitor, the first Union ironclad warship.

Ericsson, who also invented the screw propeller, is depicted holding a model of the Monitor. Bronze plaques in the monument’s granite base depict a number of Ericsson’s designs.

A dedication on the north face of the monument’s base reads, “The City of New York erects this statue to the memory of a citizen whose genius has contributed to the greatness of the republic and the progress of the world.”

The statue was created by sculptor Jonathan Scott Hartley, whose other works include three of the nine busts at the Library of Congress’ Jefferson Building.

The statue was created by sculptor Jonathan Scott Hartley, whose other works include three of the nine busts at the Library of Congress’ Jefferson Building.

Hartley’s first statue of Ericsson was dedicated in 1893, but Hartley, not satisfied with the original work, created a newer version that was dedicated in 1903.

The statue, which carries the 1893 date on its pedestal, was restored in 1996.

Ericsson is also honored with a bust on the base of a 1906 monument in New Haven honoring shipping and railroad investor Cornelius S. Bushnell, who help finance the development of the Monitor.

Tags: New York

A sculpture damaged in the September 11 attack on New York’s World Trade Center now stands as a temporary memorial to the terrorists’ victims.

A sculpture damaged in the September 11 attack on New York’s World Trade Center now stands as a temporary memorial to the terrorists’ victims.

The Sphere, created by German sculptor Fritz Koenig, was moved to Battery Park in March of 2002 and an eternal flame was lit on the one-year anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

The 25-foot sculpture, originally meant to symbolize world peace through international trade, was first erected in a fountain that stood in the plaza between the trade center’s two towers.

After the attack, the damaged sculpture was recovered from the trade center rubble and placed into storage before it was put on display, with a new base, in the park (a short walk from the trade center site).

The Sphere stands almost in the shadow of a flagpole and base, dedicated in 1926, that honors the establishment of the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam in lower Manhattan.

The Sphere stands almost in the shadow of a flagpole and base, dedicated in 1926, that honors the establishment of the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam in lower Manhattan.

A dedication on the monument’s west face reads, “On the 22nd of April 1625, the Amsterdam chamber of the West India Company decreed the establishment of Fort Amsterdam and the creation of the adjoining farms. The purchase of the island of Manhattan was accomplished in 1626. Thus was laid the foundation of the City of New York.”

The south face of the flagpole’s base depicts a Dutch trader purchasing Manhattan from a Native American, and also bears a dedication reading, “In testimony of ancient and unbroken friendship, this flagpole is presented to the City of New York by the Dutch people, 1926.”

The east face bears an inscription, in Dutch, that we presume matches the English inscription on the west face.

The east face bears an inscription, in Dutch, that we presume matches the English inscription on the west face.

The north face bears a bas-relief map of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam shortly after its founding.

The monument was created by Dutch sculptor H.A. Van den Eyden.

The Dutch settlers of New Amsterdam surrendered to British forces in 1664, and New Amsterdam was renamed New York.

Tags: New York