The 8th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, has a monument at Antietam along Harpers Ferry Road.

The 8th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, has a monument at Antietam along Harpers Ferry Road.

The monument near a large granite obelisk honoring the 9th New York (Hawkins’ Zouaves).

The west side of the monument bears an inscription reading, “8th Conn. Vol. Infantry. 2d Brigade, 3d Division, 9th Corps.”

The east side features the CT seal and an inscription reading, “Advanced position, 8th Conn. V.I., Sept 17, 1862. Engaged 400. Killed and wounded 194.” Or so we’ve read.

The east side features the CT seal and an inscription reading, “Advanced position, 8th Conn. V.I., Sept 17, 1862. Engaged 400. Killed and wounded 194.” Or so we’ve read.

The 8th CT was mustered into service in October of 1861, and served throughout the war. At Antietam, the 8th fought as part of the Army of the Potomac’s left flank.

The walkway also includes a cannon honoring the mortal wounding of Isaac Rodman of Rhode Island, who commanded the division during the battle.

Tags: Antietam

During the Battle of Antietam, the 11th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, was involved in fierce fighting near Burnside Bridge.

During the Battle of Antietam, the 11th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, was involved in fierce fighting near Burnside Bridge.

The 11th Regiment, mustered into service in October 1861, was deployed on the east side of Antietam Creek and supported attacks against Confederates on the ridges above the creek’s west side.

The west face of the monument, a short walk south from Burnside Bridge, bears the regiment’s name, the Connecticut seal and a bronze plaque depicting fighting near the bridge.

The south face of the monument identifies the 11th as a member of the Second Brigade.

The east face lists the names of 39 regimental members killed in the battle, including its commander, Henry Kingsbury, Jr., and Capt. John Griswold, who led two companies into battle. The east face also lists the unit’s membership in the Ninth Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

The east face lists the names of 39 regimental members killed in the battle, including its commander, Henry Kingsbury, Jr., and Capt. John Griswold, who led two companies into battle. The east face also lists the unit’s membership in the Ninth Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

The north face lists the regiment’s affiliation with the Corps’ Third Division.

The monument, like the other Connecticut regimental monuments at Antietam, was dedicated on October 11, 1894.

During the battle, the regiment had 139 killed and wounded, a total that included every field officer. After the battle, Griffin Stedman, who is honored with a monument on Hartford’s Campfield Avenue, was appointed regimental colonel.

Tags: Antietam

A noted Civil War infantry unit that saw its first combat during the Battle of Antietam is honored with a monument near the battle’s Bloody Lane.

A noted Civil War infantry unit that saw its first combat during the Battle of Antietam is honored with a monument near the battle’s Bloody Lane.

The 14th Regiment of the Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, recruited primarily from towns in central Connecticut, was mustered into service in August of 1862. Less than three weeks later the untested troops were engaged in some of the heaviest fighting of the Civil War.

A granite obelisk honoring the regiment stands a short distance from the sunken farm road at Antietam that became known as Bloody Lane after the roadway was used for an early example of trench warfare.

The front (south) face of the monument reads, “The Fourteenth Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 2nd Army Corps,” and provides a detailed description of the regiment’s activities during the Battle of Antietam.

The regiment advanced in a charge to the location of the monument, for instance, then fell back 88 yards to a cornfield fence and held that position under fire for nearly two hours before being deployed to another position.

The regiment advanced in a charge to the location of the monument, for instance, then fell back 88 yards to a cornfield fence and held that position under fire for nearly two hours before being deployed to another position.

The clover on the south face was the Second Corps emblem.

The monument’s east face bears an inscription reading, “This monument stands on the line of companies B and G, near the left of the regiment. In this battle, the regiment lost 38 killed and mortally wounded, 68 wounded and 21 reported missing.”

The north face bears the Connecticut seal and an inscription reading, “Erected by the State of Connecticut, 1894.”

The west face bears a United States seal and provides a summary of the unit’s history. The regiment mustered into service August 23, 1862, with 1,015 men, and was engaged 34 times between Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in 1865.

During its service, 202 members were killed or mortally wounded, 186 died of disease, 549 were wounded, and 319 were discharged for disability.

During its service, 202 members were killed or mortally wounded, 186 died of disease, 549 were wounded, and 319 were discharged for disability.

The 14th also performed admirably at Gettysburg, and we’ll profile their service there in a post next month.

Tags: Antietam

Connecticut native and Civil War General Joseph K.F. Mansfield is honored with two monuments near the site of his mortal wounding on the Antietam battlefield.

Connecticut native and Civil War General Joseph K.F. Mansfield is honored with two monuments near the site of his mortal wounding on the Antietam battlefield.

Mansfield, commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Twelfth Corps, was wounded as he led troops into battle early on the morning of September 17, 1862.

The larger of the two monuments honoring the general features a pink granite column topped with a sphere. The monument was dedicated in 1900 and stands near Antietam’s East Woods, at intersection of Smoketown Road and Mansfield Avenue.

A dedication on the west side of the monument’s base reads, “Major General, Joseph K. F. Mansfield, commanding the 12th Corps, Army of the Potomac. Mortally wounded near this spot, September 17, 1862, about 7:35 A.M., while deploying his corps in action.”

A dedication on the west side of the monument’s base reads, “Major General, Joseph K. F. Mansfield, commanding the 12th Corps, Army of the Potomac. Mortally wounded near this spot, September 17, 1862, about 7:35 A.M., while deploying his corps in action.”

The south face features a bronze plaque with the Connecticut shield and an inscription reading, “Erected by the State of Connecticut A.D. 1900 under the auspices of Mansfield Post No. 53, Department of Connecticut G.A.R.”

The G.A.R. refers to the Grand Army of the Republic, the post-Civil War veterans’ organization. The Mansfield Post was established in Middletown, the general’s adopted hometown.

The plaque featuring the Connecticut seal is a 2002 reproduction sponsored by the reenactment and preservation group Company G, 14th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865. The new plaque was modeled after a similar one on the Gen. John Sedgwick monument at Gettysburg.

The plaque featuring the Connecticut seal is a 2002 reproduction sponsored by the reenactment and preservation group Company G, 14th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865. The new plaque was modeled after a similar one on the Gen. John Sedgwick monument at Gettysburg.

The east side of the monument’s base is not inscribed, and the north face bears an inscription reading, “The spot where Gen. Mansfield fell is a few yards easterly from this monument. Born December 22, 1803. Killed September 17, 1862.”

Mansfield, a New Haven native, was a career Army officer who served in the Corps of Engineers after graduating from West Point. During his military service, Mansfield lived in Middletown. He served during the Mexican-American War in the 1840s.

As the Civil War started, Mansfield helped design defense plans for Washington, D.C. He assumed command of the Twelfth Corps a few days before the Battle of Antietam.

As the Civil War started, Mansfield helped design defense plans for Washington, D.C. He assumed command of the Twelfth Corps a few days before the Battle of Antietam.

After his death, Mansfield was buried in Middletown’s Indian Hill Cemetery. A monument and plot for other Civil War veterans stands near the general’s grave.

Wounding Monument

An inverted cannon memorial, a short walk east from the larger monument at Antietam, also honors Mansfield’s wounding. The cannon has a plaque reading, “Major General Joseph K.F. Mansfield, U.S.A., mortally wounded 38 yards N. 70° W.”

The precision with which the plaque on the cannon specifies where Mansfield was wounded may not be accurate, since veterans of the battle argued about the location where he was shot (as well as the color of the horse he was riding) for years after the battle.

The precision with which the plaque on the cannon specifies where Mansfield was wounded may not be accurate, since veterans of the battle argued about the location where he was shot (as well as the color of the horse he was riding) for years after the battle.

Disagreements about the specific location of Civil War incidents were common after the war, and understandable if you consider veterans were returning, 20 or 30 years later, to sites they had visited once during the confusion of a battle.

Tags: Antietam

Connecticut honors law enforcement officers lost in the line of duty with a monument in Meriden.

Connecticut honors law enforcement officers lost in the line of duty with a monument in Meriden.

The Connecticut Law Enforcement Memorial, on the grounds of the state’s police academy on Preston Drive, honors 135 officers, dating back to 1855, who have been killed on duty.

A black granite obelisk in the center of the memorial bears a dedication reading, “Dedicated to those who have made the ultimate sacrifice.” Names of fallen officers are inscribed on the obelisk as well as on the memorial’s granite columns.

An eternal light, inscribed with the words “Never forget” on its base, stands in front of the memorial.

An eternal light, inscribed with the words “Never forget” on its base, stands in front of the memorial.

The memorial, spearheaded by the Connecticut Police Chief’s Association, was dedicated in 1989.

Every May, a memorial ceremony is held at the site. The 2011 ceremony is scheduled on May 18.

Tags: Meriden

New York honors a World War I infantry regiment with a memorial grove in Central Park.

New York honors a World War I infantry regiment with a memorial grove in Central Park.

The 307th Infantry Memorial Grove, not far from the park’s band shell and the 7th Regiment Civil War monument, honors regimental members killed in the war.

A boulder near the center of the grove is inscribed on its south face with a dedication reading, “To the dead of the 307th Infantry A.E.F., 590 officers and men, 1917-1919

The monument’s north face displays a plaque listing more than 560 names as well as battles in which the regiment fought. The plaque is a replacement for the original.

The grove, dedicated in 1925, also has a number of trees with markers near their bases that list members of specific companies. Not every marker has a tree, perhaps reflecting the difficulty of maintaining a memorial grove more than 85 years after its dedication.

The grove, dedicated in 1925, also has a number of trees with markers near their bases that list members of specific companies. Not every marker has a tree, perhaps reflecting the difficulty of maintaining a memorial grove more than 85 years after its dedication.

The A.E.F. on the boulder’s inscription refers to the American Expeditionary Forces, U.S. troops who fought with British and French troops against the German military. One of the 307th’s major campaigns was the Meuse-Argonne offensive along the Western Front in 1918.

The grove also has an undated granite marker honoring members of the fraternal organization Knights of Pythias killed in the First World War.

Tags: New York

New York honors Union General William Tecumseh Sherman with a Saint-Gaudens statue at an entrance to Central Park.

New York honors Union General William Tecumseh Sherman with a Saint-Gaudens statue at an entrance to Central Park.

The Sherman statue, at the park southeast entrance at Fifth Avenue and West 59 Street, was the last major work by noted sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

The monument, dedicated in 1903, depicts the general atop his horse being led by Nike, the goddess of victory. Nike holds a palm branch, representing peace, aloft in her left hand.

A dedication on the south face of the monument’s base reads, “To General William Tecumseh Sherman, born Feb. 8, 1820, died Feb. 14, 1891. Erected by citizens of New York under the auspices of the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York.”

Pine branches and needles near the horse’s rear hooves represent Sherman’s Civil War march through Georgia and the Carolinas.

Pine branches and needles near the horse’s rear hooves represent Sherman’s Civil War march through Georgia and the Carolinas.

Along with the incredible detail, the statue is notable for its gold leaf covering. The gold leaf, which has worn off in several places, was reapplied during a 1989 restoration of the monument and the nearby Pulitzer Fountain. Immediately after the restoration, the monument was a bright gold, and almost painful to look at on sunny days.

Sherman, an Ohio native, lived in New York after his retirement from the military. The general and Saint-Gaudens met several times before Sherman’s death, with the general posing and sharing war stories with the sculptor.

Saint-Gaudens had hoped to place the monument near U.S. Grant’s tomb, but objections from both generals’ families led to the consideration of other sites before the Central Park location was selected.

Saint-Gaudens had hoped to place the monument near U.S. Grant’s tomb, but objections from both generals’ families led to the consideration of other sites before the Central Park location was selected.

Manhattan’s Grand Army Plaza is one of two in New York, with the other being near Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

Tags: New York

The World War I service of New York’s 107th infantry regiment is honored with a large bronze sculpture in Central Park.

The World War I service of New York’s 107th infantry regiment is honored with a large bronze sculpture in Central Park.

The 107th Regiment Monument, dedicated in 1927, features seven soldiers, in a variety of poses, on a large granite base. Three soldiers in the middle are charging, the soldier on the far right (as you face the monument) is preparing to throw hand grenades, and the second soldier from the left is supporting a badly wounded comrade.

The east face of the monument’s base bears an inscription reading, “Seventh Regiment New York, One Hundred and Seventh United States Infantry, in memoriam, 1917-1918.”

The “Seventh Regiment” description on the base refers to the unit’s designation while it served in the New York National Guard. The unit, which traces its roots to 1806, was combined with other regiments and designated as the 107th during World War I.

The “Seventh Regiment” description on the base refers to the unit’s designation while it served in the New York National Guard. The unit, which traces its roots to 1806, was combined with other regiments and designated as the 107th during World War I.

As active fighting began, the regiment had nearly 3,000 officers and men. During the war, the unit suffered 1,918 casualties (1,383 wounded, 437 killed and 98 who later died from wounds).

The unit’s Civil War service is honored with a monument on the west side of Central Park.

The monument was designed by sculptor Karl Morningstar Illava, who had served as a sergeant in the unit during World War I.

The monument was designed by sculptor Karl Morningstar Illava, who had served as a sergeant in the unit during World War I.

The monument stands along the Fifth Avenue edge of the park at East 67th Street.

Tags: New York

New York honors the Civil War service of a notable National Guard Unit with a monument in Central Park.

New York honors the Civil War service of a notable National Guard Unit with a monument in Central Park.

The 7th Regiment Monument, dedicated in 1874, features a bronze soldier standing atop a granite base. A dedication on the east face of the monument’s base reads, “The Seventh Regiment Memorial of 1861-1865.”

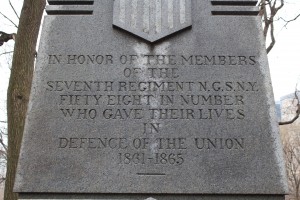

The north and south faces bear a dedication reading, “In honor of the members of the Seventh Regiment, N.G.S.N.Y., fifty eight in number, who gave their lives in defence of the Union, 1861-1865.”

The west face reads, “Erected by the Seventh Regiment National Guards S.N.Y., MDCCCLXXIII” (1873).

The west face reads, “Erected by the Seventh Regiment National Guards S.N.Y., MDCCCLXXIII” (1873).

The four sides of the monument’s base also feature bronze trophies inscribed with the regiment’s motto, the Latin phrase “pro patria et gloria” (for country and glory).

The monument stands in its original location near the park’s West Loop, not far from the band shell.

The regiment traces its roots to 1806, when it was organized as a militia unit. After protecting New York harbor during the War of 1812 and suppressing a number of local riots, the unit served in the Civil War and both World Wars.

The 7th Regiment was renamed the 107th during World War I, and its service during that conflict is honored with a monument on Fifth Avenue and East 67 Street.

The 7th Regiment was renamed the 107th during World War I, and its service during that conflict is honored with a monument on Fifth Avenue and East 67 Street.

The unit’s Civil War monument was created by sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward, whose other works include the statue of Roscoe Conkling in New York’s Madison Square Park.

In the stereo image titled, “A View of Central Park,” the gentleman wearing an apron and holding a large mallet may be Ward. He is not identified in the image, but both Ward and this person had generous beards, and Ward probably wore an apron and used a large mallet at least part of the time.

The image also provides an interesting view of how Central Park West has changed since the monument’s dedication.

The image also provides an interesting view of how Central Park West has changed since the monument’s dedication.

Tags: New York

Eastford honors its war veterans with a monument on the green in front of its public library.

Eastford honors its war veterans with a monument on the green in front of its public library.

The monument, a granite block with bronze plaques, stands at the intersections of Eastford Road (Route 198) with Westford and Old Colony roads.

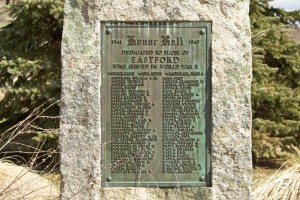

The monument’s south face features a bronze Honor Roll plaque listing about 63 names of World War II veterans. The monument indicates the three Eastford residents killed in the war.

On the monument’s north face, the upper plaque reads, “In memory of Eastford men who served: Six or more in the American Revolution, two in the War of 1812, two in the Mexican War, one in the Spanish-American War and Gen. Nathaniel Lyon and those 89 comrades of the Civil War. Let those who shall come after see that these men shall not be forgotten.”

The lower Honor Roll plaque lists 19 residents who served in World War I.

The lower Honor Roll plaque lists 19 residents who served in World War I.

The monument is undated, but the “World War” reference probably indicates it was originally dedicated in the 1920s or 30s.

Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, the first Union general killed in the Civil War, is buried in Eastford’s General Lyon Cemetery.

Tags: Eastford