Boston honors its Civil War veterans with a 72-foot high monument near the center of Boston Common.

Boston honors its Civil War veterans with a 72-foot high monument near the center of Boston Common.

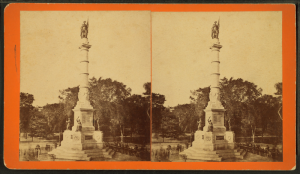

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, originally known as the Army and Navy Monument, was dedicated in 1877 at the top of a small hill near the Common’s Frog Pond.

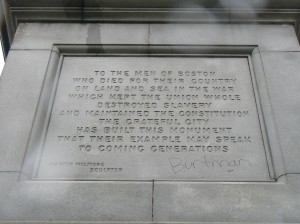

A dedication on the monument’s west face reads, “To the men of Boston who died for their country, on land and sea, in the war which kept the Union whole, destroyed slavery and maintained the Constitution. The grateful city has built this monument that their example may speak to coming generations.”

The monument’s base has four bronze bas-relief plaques depicting war-related scenes. The tablets illustrate the departure and return of local residents, a naval battle against a Confederate fort, and the work of the Boston Sanitary Commission (a civilian group that treated wounded troops).

The monument’s column is topped by a bronze allegorical statue representing America. She stands with a sword and laurel wreaths in her right hand and cradles a flag in her left arm.

The four granite figures on the column’s shaft represent the northern, southern, eastern and western sections of the reunited nation.

The four granite figures on the column’s shaft represent the northern, southern, eastern and western sections of the reunited nation.

Unfortunately, the monument carries several vandalism scars. Along with the obvious graffiti in several locations, miscreants have pried the heads from several figures in the bas-relief scene depicting the return of the troops.

As you can see in the stereograph image, the monument originally also had four bronze statues on its corner pedestals. The statues represented a soldier and a sailor, peace and history. The statues have been removed in recent years to prevent further deterioration.

The monument was designed by sculptor Martin Milmore, who created a number of public works and monuments in the greater Boston area before dying in 1883 at the age of 38.

Dedication Day

U.S. attorney general Charles Devens, for whom Fort Devens was named, was one of the featured speakers at the monument’s dedication on September 17, 1877. In his remarks, Devens pointed out that the date marked not only the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, it also was also the anniversary of the adoption of the U.S. Constitution 90 years earlier and the founding of Boston in 1630.

Devens, a native of Charlestown, Mass., practiced law before serving in the Civil War. Devens was promoted to brigadier general and would be wounded three times during the war.

Devens is depicted in the bas-relief scene illustrating the return of the troops. Of the two figures on horseback under the blue graffiti, Devens is on your right.

Devens is depicted in the bas-relief scene illustrating the return of the troops. Of the two figures on horseback under the blue graffiti, Devens is on your right.

Nearby Monuments

The plaza surrounding the Soldiers’ and Sailor’s Monument includes two other noteworthy monuments. A 1959 plaque affixed to a small boulder honors the service of military nurses.

To the east of the monument, a naval mine mounted on a carriage honors the placement of more than 56,000 mines in the North Sea during World War I. The mine monument was dedicated in 1921.

Monuments on both sides of the Old North Bridge in Concord, Mass., mark the site of the first militia victory in the American Revolution.

Monuments on both sides of the Old North Bridge in Concord, Mass., mark the site of the first militia victory in the American Revolution.

The famous “shot heard ‘round the world” was fired on April 19, 1775, by a member of a militia raised from Concord and nearby towns including Acton, Bedford and Lincoln.

The troops, nicknamed “minutemen,” repulsed British troops that had marched from Boston to Concord to search for weapons and ammunition being stored at a Concord farm.

The west, or “American” side of the bridge features the Minute Man, a famous statue created by sculptor Daniel Chester French. The statue depicts a farmer who is walking away from his plow, rifle in hand, to fight for what would become a new nation.

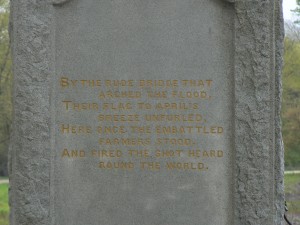

The Minute Man, dedicated in 1885 to mark the 100th anniversary of the skirmish, features an inscription from an Emerson’s “Concord Hymn” reading, “By the rude bridge that arched the flood, their flag to April’s breeze unfurled, here once the embattled farmers stood and fired the shot heard ‘round the world.”

The Minute Man, dedicated in 1885 to mark the 100th anniversary of the skirmish, features an inscription from an Emerson’s “Concord Hymn” reading, “By the rude bridge that arched the flood, their flag to April’s breeze unfurled, here once the embattled farmers stood and fired the shot heard ‘round the world.”

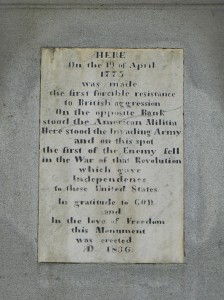

On the east (“British) side of the river, the first monument commemorating the fighting at North Bridge was dedicated in 1836. The obelisk features an inscription on its east face reading, “Here on the 19 of April 1775 was made the first forcible resistance to British aggression. On the opposite bank stood the American Militia. Here stood the Invading Army and on this spot the first of the Enemy fell in the War of that Revolution which gave Independence to these United States. In gratitude to God and in the love of Freedom this Monument was dedicated. AD 1836.”

As you face the 1836 monument, to your left is a gravesite for two British troops killed in the skirmish (a third was buried in Concord Center).

As you face the 1836 monument, to your left is a gravesite for two British troops killed in the skirmish (a third was buried in Concord Center).

The Minute Man was the first major monument for French, who would later sculpt the statue of Abraham Lincoln in Washington’s Lincoln Memorial. The Minute Man image serves as the logo for the U.S. National Guard, appears on savings bonds, and was on the back of the 2000 quarter honoring Massachusetts.

The statue was cast from former Civil War cannons (which was common for monuments created in that era).

Today’s version of Old North Bridge, which stands over the Concord River, was built in 1956 and restored in 2005. The bridge is the fifth to stand on that location, which is vulnerable to flooding that has claimed several bridges over the years.

About a quarter-mile away from the bridge, a former homestead has been converted into the North Bridge Visitor’s Center. In front of the center, a monument honors Major John Buttrick, a local farmer and militia leader who led the minutemen down the hillside toward North Bridge.

About a quarter-mile away from the bridge, a former homestead has been converted into the North Bridge Visitor’s Center. In front of the center, a monument honors Major John Buttrick, a local farmer and militia leader who led the minutemen down the hillside toward North Bridge.

Tags: Massachusetts

The first major battle of the American Revolution is commemorated with a large granite obelisk in the Charlestown section of Boston.

The first major battle of the American Revolution is commemorated with a large granite obelisk in the Charlestown section of Boston.

The 221-foot obelisk was dedicated in 1843 to honor the Battle of Bunker Hill, which was fought on June 17, 1775, on Breed’s Hill (more about the hills later).

Inside the monument, 294 steps lead to observation windows just below the monument’s peak. The monument was closed at the time of our visit, sparing us the decision about whether to attempt the climb.

The battle was the first major engagement for Continental troops, who were defending a hastily constructed fort against British forces. The Continental troops repelled the attackers twice before an ammunition shortage prompted their retreat.

Although the Continental forces lost the battle, their strong showing and the large number of British casualties (nearly half of the 2,200 troops) demonstrated the viability of the Continental troops and provided a strong moral victory.

The granite building at the monument’s east base was completed in 1903 to display battlefield artifacts.

The granite building at the monument’s east base was completed in 1903 to display battlefield artifacts.

Four gateways leading to the monument site have been named after nearby states, and feature granite markers honoring a local hero. The stairways are being refurbished with federal stimulus money.

To the immediate west of the monument’s base, an 1881 statue honors Massachusetts native Colonel William Prescott. Prescott, who commanded the Continental troops along with Connecticut’s Israel Putnam and Colonel John Stark, is most commonly cited as the officer who gave the legendary command “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” (Different accounts attribute the quote to Putnam or Stark, or dispute whether anyone said it.)

The Prescott statue was created by sculptor William Wetmore Story, a Boston native who gave up a promising law career to pursue sculpture. A number of his classical female figures are displayed in U.S. museums.

The Prescott statue was created by sculptor William Wetmore Story, a Boston native who gave up a promising law career to pursue sculpture. A number of his classical female figures are displayed in U.S. museums.

Efforts to honor the battle began with a wooden monument erected in 1794 by local Masons to honor Dr. Joseph Warren, who was killed during the battle.

A movement began to erect a more prominent monument, and the obelisk’s cornerstone was laid in 1825 during ceremonies marking the battle’s 50th anniversary.

Funding challenges stalled construction over the years, and the committee raised funds for the monument by selling a good chunk of the battlefield for real estate development.

Confusion about the battle’s name and location started before the first shot had been fired. Prescott had been ordered to fortify nearby Bunker Hill, but the Continental commanders decided Breed’s Hill would be more suitable. A British cartographer mapping the battlefield reversed the names of the two hills, and Breed’s Hill was consigned to the historical shadow of its more famous neighbor.

The Bunker Hill site was administered by a private association until it was turned over the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1919. In 1976, the site was transferred to the National Park Service and added to Boston’s Freedom Trail.

The Bunker Hill site was administered by a private association until it was turned over the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1919. In 1976, the site was transferred to the National Park Service and added to Boston’s Freedom Trail.

Tags: Massachusetts

Southington’s Civil War veterans are honored with an 1880 monument in the center of the town green.

Southington’s Civil War veterans are honored with an 1880 monument in the center of the town green.

The granite Soldiers’ Monument depicts a clean-shaven Civil War soldier standing with a rifle. A relatively simple dedication on the front (east) face reads, “The defenders of our Union. 1861-1865.”

The east face also features an intricate carving of the Connecticut and United States shields and a raised ribbon with the state motto. The monument’s other faces do not bear any inscriptions.

While the monument has comparatively little lettering, it has a number of decorative elements not commonly seen on Civil War monuments, such as the four blue granite columns at each corner and the ornamental gables just below the soldier’s feet.

The monument was created by Charles Conrads, the principal sculptor for James Batterson’s New England Granite Works. Batterson’s firm supplied many Civil War monuments in Connecticut.

The monument was created by Charles Conrads, the principal sculptor for James Batterson’s New England Granite Works. Batterson’s firm supplied many Civil War monuments in Connecticut.

North of the green, which was laid out in 1876, a memorial flagpole dedicated after World War I honors veterans of that and the nation’s earlier wars. On the east and north faces of the flagpole’s base, bronze tablets list veterans of World War I (in four columns on each tablet).

On the west side, a tablet has four columns listing Southington’s Civil War veterans. On the south side, veterans of the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American War are honored.

South of the Civil War monument, a collection of memorials honors veterans of World War II, Korea, Vietnam and the ongoing fight against terrorism. The central granite tablet bears a dedication inscribed below a carved eagle. The left two memorials feature bronze tablets listing World War II veterans in 10 long columns of names, and honoring 33 residents who were killed in the conflict.

The two memorials on the right honor veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam. The Korean War memorial list veterans in six columns and honors one who was killed. The Vietnam memorial also has six columns of names and honors 10 who were killed.

The two memorials on the right honor veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam. The Korean War memorial list veterans in six columns and honors one who was killed. The Vietnam memorial also has six columns of names and honors 10 who were killed.

Tags: Southington

After an extensive restoration, Bridgeport this week rededicated a memorial fountain honoring sewing machine manufacturer and civic leader Nathaniel Wheeler.

After an extensive restoration, Bridgeport this week rededicated a memorial fountain honoring sewing machine manufacturer and civic leader Nathaniel Wheeler.

The 1912 fountain at the intersection of Park Avenue, Fairfield Avenue and John Street, was rededicated April 20 after a long repair project that has restored the long-dormant flow of water to the fountain.

The fountain features a mermaid carrying an infant and a light fixture as large fish splash around her flippers. A dedication on the fountain’s base reads, “The Nathaniel Wheeler Memorial, erected 1912,” below the years of Wheeler’s life (1820-1893).

Water will spout from four cherub heads surrounding the fountain’s main bowl.

Water will spout from four cherub heads surrounding the fountain’s main bowl.

Smaller fountains at the corners of the triangular traffic island surrounding the fountain site feature a mermaid, several seals and three seahorses.

During the restoration, the traffic island was ringed with granite bollards, which should help protect the fountain from automobiles.

The fountain was created by sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who is perhaps better known for his work at Mount Rushmore.

Wheeler, a native of Watertown, was the son of carriage manufacturer. Wheeler shifted into manufacturing machinery and began sewing machine production in 1851. By 1856, the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Co. had moved to Bridgeport, where it would eventually grow into one of the world’s leading producers of sewing machines.

Wheeler would later serve in the Connecticut legislature and as a director of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad as well as Peoples’ Bank. He was also involved in many social and civic causes in Bridgeport.

Wheeler was a descendent of Moses Wheeler, a resident of colonial Stratford who operated a ferry across the Housatonic River between Stratford and Milford. The interstate 95 bridge across the Housatonic bears Moses Wheeler’s name.

Wheeler was a descendent of Moses Wheeler, a resident of colonial Stratford who operated a ferry across the Housatonic River between Stratford and Milford. The interstate 95 bridge across the Housatonic bears Moses Wheeler’s name.

The Wheeler Memorial Fountain was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Wheeler & Wilson superintendent William H. Perry is honored with the memorial arch at the Park Avenue entrance to Bridgeport’s Seaside Park.

Tags: Bridgeport

Berlin honors local war veterans with a collection of memorials on Worthington Ridge.

Berlin honors local war veterans with a collection of memorials on Worthington Ridge.

The monument site is dominated by a 1920 obelisk topped by a large eagle. A dedication on the east side of the obelisk’s base reads, “Erected by the town of Berlin in honor of her patriotic men and women who served their country in time of war. For the dead, a tribute. For the living, a memory. For posterity, an emblem of loyalty to the flag of their country.”

The other three sides of the monument have simple plaques listing a war and the dates in which it was fought. The north side honors World War I, the west side honors the Spanish-American War and the south side honors the Civil War.

Behind the obelisk is a curved brick pergola that features four monuments honoring veterans of the two World Wars, Korea and Vietnam.

Behind the obelisk is a curved brick pergola that features four monuments honoring veterans of the two World Wars, Korea and Vietnam.

World War I veterans are honored with a two-sided memorial at the south end of the pergola. Both sides bear two columns of names listing residents who served in the war. The west face of the World War monument honors five residents killed in the conflict, including one who died in Red Cross service. The west face also honors four nurses and five members of the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC), the forerunner of today’s ROTC.

World War II veterans are honored with a similar two-sided tablet, each with four columns of names. The east face bears a dedication and honors 22 veterans killed in the conflict.

Veterans of the Korean and Vietnam wars are honored with single-sided tablets. The Korean War memorial has two columns of residents listed, and honors one resident killed in action. The Vietnam memorial, which has four columns of names, honors three residents killed in action and one who was reported missing.

Veterans of the Korean and Vietnam wars are honored with single-sided tablets. The Korean War memorial has two columns of residents listed, and honors one resident killed in action. The Vietnam memorial, which has four columns of names, honors three residents killed in action and one who was reported missing.

A military cannon facing west has been mounted in the central section of the pergola, between the World War II and Korean War memorials.

A granite marker installed in front of the obelisk honors 21 residents who served in Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Granite planters in the front of the monument site honor the branches of the military.

The monument stands in a triangular area at the intersection where Farmington Avenue and Wildem Road meet Worthington Ridge.

Berlin’s Civil War veterans are honored with brownstone monuments in East Berlin and the town’s Kensington section. The Kensington monument, dedicated in 1863, may well be the first Civil War monument erected in the United States.

Tags: Berlin

Shelton honors veterans lost in World War II with a bronze plaque outside the Plumb Memorial Library.

Shelton honors veterans lost in World War II with a bronze plaque outside the Plumb Memorial Library.

The monument, dedicated in 1947, bears a dedication reading, “In memory of those who died in service,” above three columns containing 34 names. The monument also features a bronze eagle standing above crossed flags, the U.S. shield and the Army and Navy logos.

The monument stands in front of Shelton’s Plumb Memorial Library. The library was named for David Wells Plumb, a local businessman who served as president of Shelton’s first library, which opened in 1892 on the second floor of a downtown building. Plumb was advocating for a dedicated library when he died suddenly in 1893. After his death, his wife donated land and Plumb’s brother Horace financed the construction of the library building. The Plumb Memorial Library was dedicated in December of 1894, and was expanded in 1974.

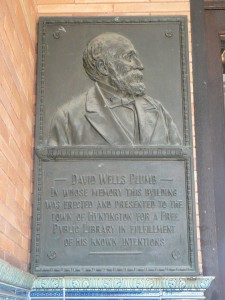

David Wells Plumb is honored with a plaque just outside what used to be library’s main entrance on Wooster Street. The plaque depicts Wells and bears a dedication reading, “David Wells Plumb, in whose memory this building was erected and presented to the town of Huntington for a free public library in fulfillment of his known intentions.”

David Wells Plumb is honored with a plaque just outside what used to be library’s main entrance on Wooster Street. The plaque depicts Wells and bears a dedication reading, “David Wells Plumb, in whose memory this building was erected and presented to the town of Huntington for a free public library in fulfillment of his known intentions.”

(Today, Huntington is a section within the city of Shelton, which was incorporated in 1917.)

Shelton’s World War II veterans are also honored with a monument along the downtown riverwalk.

Tags: Shelton

New Britain honors its World War I heroes and veterans with a 90-foot column in Walnut Hill Park.

New Britain honors its World War I heroes and veterans with a 90-foot column in Walnut Hill Park.

The tall stone column, topped by two sculpted eagles, bears a dedication at its front (north) base reading, “MDCCCCXXVII (1927). The city of New Britain here records with pride that of her citizens, more than four thousand served in the World War 1917-1918.”

The plaque also has symbols representing the Army, the Navy, industry and the Red Cross. It appears that bronze ornamentation that once surrounded this plaque has been removed.

A dedication plaque on the south base of the column reads, “To her sons who gave their lives to their country, their names are here inscribed. Their memory lives in the heart of a grateful city.”

Just below the eagles, the column appears to be wrapped with a flag that’s draped over the column’s fluting.

Just below the eagles, the column appears to be wrapped with a flag that’s draped over the column’s fluting.

Surrounding the monument are two semi-circular walls bearing bronze plaques that list the name, rank, unit affiliation and date of death for 123 residents (61 plaques on the west side, and 62 plaques on the east side). Bronze poppies can be seen between the plaques. Ornamental palms at the ends of the rows of names also appears to have been removed.

Four large light fixtures near the monument are decorated with butterflies symbolizing renewal and resurrection.

New Britain dedicated its World War I monument on September 22, 1928. The monument was designed by Harold Van Buren Magonigle, who also created a similar monument in Kansas City as well a firefighters’ monument on Riverside Drive in New York City.

The stone column replaced an honor roll and memorial near one of the park’s entrances.

The stone column replaced an honor roll and memorial near one of the park’s entrances.

Just south of the World War I monument, a 1999 monument honors the contributions of women to the nation’s wars.

With our usual poor timing, our visit came just before the planting of more than 750 rose bushes by the Friends of the Walnut Hill Park Rose Garden in the courtyard south of the monument.

Tags: New Britain

The town of Plymouth honors veterans of recent wars with three monuments in a Main Street park.

The town of Plymouth honors veterans of recent wars with three monuments in a Main Street park.

The Plymouth Veterans’ Monument, near the intersection of Main Street (Route 6) and North Main Street, features a monument honoring the two World Wars and Korea, as well as a separate monument commemorating the Vietnam War.

The two World Wars and Korea are honored with an undated granite monument that features three bronze plaques listing local veterans. An eagle is inscribed on the central column, as is a dedication reading, “Dedicated in memory of the men and women of the town of Plymouth, Conn., who served their country in World War I, World War II [and the] Korean War.”

Beneath this dedication, a plaque lists the names of eight residents killed in World War I, 25 killed in World War II and two killed in Korea.

Beneath this dedication, a plaque lists the names of eight residents killed in World War I, 25 killed in World War II and two killed in Korea.

On the left and right sides of the monument, plaques list approximately 200 World War I veterans and about 700 residents who served in World War II.

To the immediate left of the Veteran’s Monument, a granite monument honors residents who served in the Vietnam War. Six residents who died in the conflict are honored above a list of an estimated 375 residents who served in the war.

A short walk northeast of the monument, a bronze plaque on a large boulder honors veterans of the two World Wars. The plaque, mounted on the boulder’s southeast face, reads, “Dedicated to the loyal sons and daughters of Plymouth, Connecticut, who served their country during World Wars I and II. Erected through the generosity of Judge Andrew W. Granniss 1953.”

The monuments are not far from the Civil War-era monuments in Terryville and about 2.5 miles west on the Plymouth Green.

The monuments are not far from the Civil War-era monuments in Terryville and about 2.5 miles west on the Plymouth Green.

Tags: Plymouth

Bristol honors its Civil War veterans with an 1866 brownstone obelisk that’s one of the state’s earliest monuments commemorating the conflict.

Bristol honors its Civil War veterans with an 1866 brownstone obelisk that’s one of the state’s earliest monuments commemorating the conflict.

The monument, on a hilltop in the city’s West Cemetery, was dedicated in January of 1866, making it perhaps the second Civil War monument in Connecticut.

(The 1863 monument in Kensington is believed to be the first in the nation, and the undated Civil War monument in Plymouth may have been dedicated in 1865 or 1866. The Bristol Soldiers’ Monument was one of five dedicated in 1866, along with monuments in Norwich, Cheshire, Northfield, Hartford and North Branford.)

The Bristol monument is a tall obelisk topped by a brownstone eagle. A dedication at the base of the monument’s front (east) side reads, “Erected by voluntary contributions in grateful remembrance of the volunteer soldiers of Bristol who gave up their lives in behalf of their country in the war of the great rebellion. The sacrifice was not in vain.”

The Bristol monument is a tall obelisk topped by a brownstone eagle. A dedication at the base of the monument’s front (east) side reads, “Erected by voluntary contributions in grateful remembrance of the volunteer soldiers of Bristol who gave up their lives in behalf of their country in the war of the great rebellion. The sacrifice was not in vain.”

The east face also lists 14 Bristol residents killed in the Civil War. The east face also features the seals of Connecticut and the United States, and a decorative trophy depicting a flag, a rifle, a sword and a cartridge pouch. The east face also honors the battle of Antietam and men who died at the Confederate prisoner of war camp in Andersonville, Ga.

The monument’s north face lists the names of 13 residents who died as prisoners of war, and two who were lost at sea. The battles of Fredericksburg (Va.) and Plymouth (N.C.) are also listed.

The west face lists 13 names, and the battles of Fort Wagner (S.C.) and Irish Bend (La.). The south face lists 12 names, and the battles of Gettysburg and New Bern (N.C.).

The monument was supplied by Hartford entrepreneur James Batterson, whose firm was responsible for a number of Civil War monuments in Connecticut and other locations.

The monument was supplied by Hartford entrepreneur James Batterson, whose firm was responsible for a number of Civil War monuments in Connecticut and other locations.

Overall, the Bristol monument is good condition considering its age. The lettering on the base of the monument’s east face is somewhat weathered and difficult to read, and cracks on the south face appear to have been patched with a material similar to auto-repair putty. Two braces have been affixed to the top of the column, just below the brownstone eagle.

A low brownstone marker in front of the monument is dedicated “To the Unknown Dead,” and a marker honoring all veterans has been placed to the west of the monument.

A number of Civil War veterans are buried in the section just east of the Soldiers’ Monument.

Tags: Bristol