A large obelisk in Putnam Memorial State Park honors American Revolution soldiers who established winter quarters in Redding.

A large obelisk in Putnam Memorial State Park honors American Revolution soldiers who established winter quarters in Redding.

Units under Gen. Israel Putnam spent the winter of 1778-79 at the site, which was chosen to allow the deployment of troops to defend towns in coastal Connecticut, New York City or the Hudson River valley.

The troops who wintered at the site, which was later nicknamed “Connecticut’s Valley Forge,” are honored with a granite obelisk, dedicated in 1888, that stands near the park’s main entrance at the intersection of Routes 58 and 107.

A dedication on the monument’s west face reads, “Erected to commemorate the winter quarters of Putnam’s division of the Continental Army, Nov. 7th 1778 – May 25th 1779.”

A dedication on the monument’s west face reads, “Erected to commemorate the winter quarters of Putnam’s division of the Continental Army, Nov. 7th 1778 – May 25th 1779.”

The monument’s south face lists the commanding officers of the winter encampment. Along with Putnam, the monument lists the surnames of Alexander McDougall, Enoch Poor, Samuel H. Parsons and Samuel Huntington.

The inscription on the east face reads, “The men of ’76 who suffered here. To preserve forever their memory, the state of Connecticut has erected this monument. A.D. 1888.”

The north face bears an inscription from Putnam reading, “The world is full of their praises, posterity stands astonished at their deeds.”

The site and surrounding park are decorated with a number of Civil War cannons. The cannon immediately in front of the obelisk was originally flanked with cannonball pyramids.

The site and surrounding park are decorated with a number of Civil War cannons. The cannon immediately in front of the obelisk was originally flanked with cannonball pyramids.

Putnam Memorial State Park, Connecticut’s first state park, was established in 1887 to honor Putnam and the troops who wintered there.

The park also features stone pits marking the location of the troops’ huts, a replica guardhouse and a series of wayside markers explaining park features.

A statue by sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington depicts Israel Putnam riding a horse down a staircase to escape from British forces in Greenwich.

Tags: Redding

Simsbury honors its Civil War veterans with an 1895 monument in its Weatogue section.

Simsbury honors its Civil War veterans with an 1895 monument in its Weatogue section.

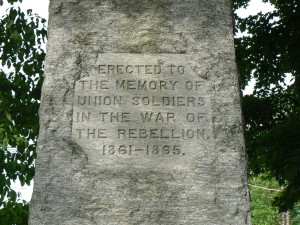

The Soldiers’ Monument features an infantryman standing with a rifle atop a rough granite pedestal. A dedication on the front (northeast) face reads, “Erected to the memory of Union Soldiers in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865.” A GAR emblem also appears on the northeast face.

The monument’s northwest and southwest sides bear large panels inscribed with the names of local Civil War veterans. The southeast side is inscribed with the names of 15 local officers.

The infantry figure has more angular appearance than most Civil War monuments. The monument was supplied by the Munson Granite Company, and the sculptor’s name isn’t readily available.

The infantry figure has more angular appearance than most Civil War monuments. The monument was supplied by the Munson Granite Company, and the sculptor’s name isn’t readily available.

At the base of the monument, a dedication plaque was added in 1995 as part of the monument’s 100th anniversary. The plaque dedicates the monument to all veterans of the Civil War, and lists 37 Simsbury residents who were lost in the conflict.

The monument stands in a small wooded area on Hopmeadow Street (Route 10), just south of the intersection with Sand Hill Road.

Simsbury honors those lost in the nation’s wars with two monuments in the center of town.

Simsbury honors those lost in the nation’s wars with two monuments in the center of town.

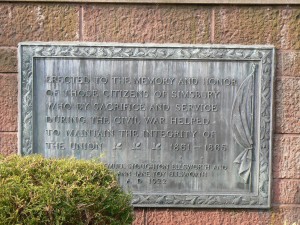

The Memorial Gateway at the entrance of Simsbury Cemetery on Hopmeadow Street (Route 10), dedicated in 1923, honors residents killed in the Civil War and World War I. The gateway features two curved fences as well as pillars topped with bronze eagles.

Plaques are mounted within the brick gateway to honor local war heroes. The south plaque, which honors Civil War veterans, bears a dedication reading, “Erected to the memory and honor of those citizens of Simsbury who, by sacrifice and service during the Civil War, helped to maintain the integrity of the Union 1861-1865.”

Plaques are mounted within the brick gateway to honor local war heroes. The south plaque, which honors Civil War veterans, bears a dedication reading, “Erected to the memory and honor of those citizens of Simsbury who, by sacrifice and service during the Civil War, helped to maintain the integrity of the Union 1861-1865.”

The north plaque bears a similar dedication to residents who served in World War I.

The north plaque bears a similar dedication to residents who served in World War I.

A large marker just inside the cemetery ground marks the location of the first meeting house in Simsbury, which was erected in 1683 and stood until 1739.

Across the street from the cemetery, a war memorial outside Eno Memorial Hall honors veterans of all wars. A dedication on the monument’s south side reads, “In memory of those from Simsbury who gave their lives in the service of their country. These dead shall not have died in vain.”

Across the street from the cemetery, a war memorial outside Eno Memorial Hall honors veterans of all wars. A dedication on the monument’s south side reads, “In memory of those from Simsbury who gave their lives in the service of their country. These dead shall not have died in vain.”

The monument lists five residents who were killed in World War I, 17 who died in World War II, two who died in Korea, and three who were lost in Vietnam.

Simsbury’s Civil War veterans are also honored with a monument that will be highlighted in a future post.

Simsbury’s Civil War veterans are also honored with a monument that will be highlighted in a future post.

Tags: Simsbury

East Haddam honors its Civil War veterans with a monument on the Moodus Green.

East Haddam honors its Civil War veterans with a monument on the Moodus Green.

The monument, dedicated in 1900, features a granite infantryman facing south. A dedication on its south face reads, “In honored memory of the brave defenders of our country in its hour of peril 1861-1865.”

The south face also honors the Battle of Gettysburg.

The east face lists the Battle of Antietam, and honors 10 residents lost in the war. The north face lists Appomattox and 14 residents, and the west face lists the Battle of Petersburg (Va.) and 10 residents.

Because the granite panels inscribed with the names were polished, the inscribed names are very difficult to discern.

The monument’s square base supports a round column draped with banners. The column is topped by the infantry figure, whose left foot extends slightly beyond the base.

The monument’s square base supports a round column draped with banners. The column is topped by the infantry figure, whose left foot extends slightly beyond the base.

The monument stands on the small green at the intersection of East Haddam Moodus Road (Route 149) and Plains Road (Route 151) in the Moodus section of East Haddam.

Immediately south of the Soldiers’ Monument is another monument honoring residents lost in World War I. A bronze plaque titled “Roll of Honor” is topped with a large eagle, the United States shield and several flags, and emblems representing the Army and the Navy.

The plaque honors one resident who died in service during the war. In the section listing Army veterans, 67 residents are honored. The monument further lists 22 residents who served with the Navy, and one who provided support services with the Y.M.C.A.

Tags: East Haddam, Moodus

A large boulder in the Devon section of Milford once served as a lookout station during the American Revolution.

A large boulder in the Devon section of Milford once served as a lookout station during the American Revolution.

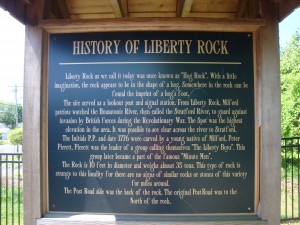

Liberty Rock, the highest point in its neighborhood, was used during the revolution to observe nearby Long Island Sound as well as the Boston Post Road.

The large boulder, originally known as Hog Rock, was renamed Liberty Rock in 1897. A brief dedication was carved into the rock’s southern face.

The rock once had a plaque under the carved dedication, but the plaque was removed at some point over the year.

The boulder is now the central feature of a small park that was restored in 2006.

During the restoration, a marker explaining the site’s history was added, as were pathways, a flagpole and stone benches. A series of small markers atop wooden stanchions added at the time have mostly been removed by vandals.

During the restoration, a marker explaining the site’s history was added, as were pathways, a flagpole and stone benches. A series of small markers atop wooden stanchions added at the time have mostly been removed by vandals.

The site stands on the Post Road, alongside the on/off ramp to Interstate 95’s Exit 34.

Tags: Milford

Stafford honors its Civil War veterans with a 1924 monument in its downtown Hyde Park.

Stafford honors its Civil War veterans with a 1924 monument in its downtown Hyde Park.

The Soldiers’ Monument in the Stafford Springs section of town features a bronze statue on its front (east) face, and is topped by a bronze eagle.

The design reflects its relatively late dedication nearly 80 years after the end of the Civil War. No battles are listed, and the monument has very little lettering.

The allegorical figure wears a hooded cloak. Her left hand carries a wreath of forget-me-nots to symbolize immortality, along with palm leaves (glory), roses (love) and poppies (eternal rest).

Near the top of the column, the east and west faces display torches along with an excerpt from the Pledge of Allegiance, “One nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

The monument’s front face also displays the years of the Civil War inside a wreath. A dedication near the base reads, “The gift of Colonel Charles Warren to the town of his nativity.”

The north and south faces bear no lettering, and display torches.

The north and south faces bear no lettering, and display torches.

The monument was funded with a bequest from Stafford native Charles Warren, a Civil War veteran who later became a merchant and banker. Warren, who died in 1920, also donated funds for the Warren Memorial Town Hall, which opened in 1924.

The monument was created by sculptor Frederic Wellington Ruckstull, who also created the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Baltimore and several busts at the Library of Congress.

Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Art Inventories Catalog

Tags: Stafford

Concord, Mass., honors its war heroes with a collection of monuments on the town green.

Concord, Mass., honors its war heroes with a collection of monuments on the town green.

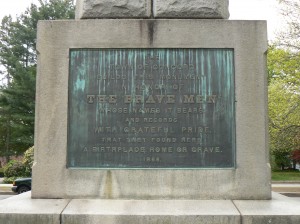

The first and largest memorial on Monument Square is the 30-foot granite obelisk honoring Concord residents killed in the Civil War. A dedication plaque on the monument’s west face reads, “The Town of Concord builds this monument in honor of the brave men whose names it bears, and records with grateful pride that they found here a birthplace, home or grave. 1866.”

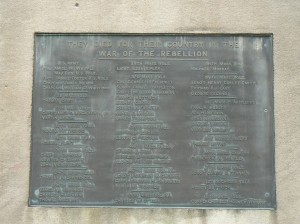

The east face features a plaque reading “They died for their country in the war of the rebellion,” and lists the names of 32 residents. Among the dead are three members of the Melvin family, who died while serving with the First Mass. Heavy Artillery.

The south face has been inscribed with the dedication, “Faithful unto death,” and the north face bears the years of the Civil War.

The monument was dedicated on April 19, 1867, the 92nd anniversary of fighting at Concord’s North Bridge at the beginning of the American Revolution. The date also marked the anniversary of the departure of Civil War troops from Concord in 1861.

The monument’s foundation contains a large granite block from the abutment of North Bridge.

The monument’s foundation contains a large granite block from the abutment of North Bridge.

The Civil War monument was designed by Hammatt Billings, an architect and artist who illustrated the first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Billings also designed the National Monument to the Forefathers in Plymouth, Mass., as well as the original platform protecting Plymouth Rock.

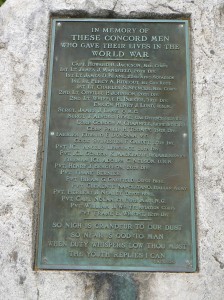

At the green’s south end, a large boulder features a plaque honoring 25 residents who died in World War I. The plaque also includes poetry verses writted by Concord resident Ralph Waldo Emerson.

At the north end of the green, a plaque affixed to a boulder honors three residents who were killed in the Spanish-American War.

Southwest of the green, a small plaza has three memorials commemorating those lost in more recent conflicts. The central monument honors the 25 residents lost in World War II. The monument on the left honors three residents killed in Korea and one lost in Iraq. The right monument honors five killed in Vietnam and one who died in the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic in 1965-66.

Southwest of the green, a small plaza has three memorials commemorating those lost in more recent conflicts. The central monument honors the 25 residents lost in World War II. The monument on the left honors three residents killed in Korea and one lost in Iraq. The right monument honors five killed in Vietnam and one who died in the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic in 1965-66.

Tags: Massachusetts

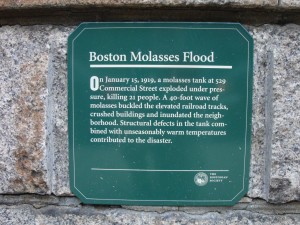

A small plaque in a Boston park marks the site of the Great Molasses Flood, which killed 21 people in 1919.

A small plaque in a Boston park marks the site of the Great Molasses Flood, which killed 21 people in 1919.

The disaster is marked with a small plaque on a playground wall near 529 Commercial Street.

The molasses flood occurred on January 15, 1919, when an industrial holding tank with 2.3 million gallons of molasses burst open. A wall of molasses surged through the neighborhood at 35 miles per hour, knocking over buildings, crushing cars and trucks, and shearing supports for an elevated railway.

The disaster killed 21 people, injured 150, and left the Commercial Street neighborhood in the city’s North End in ruins.

Immediately after the disaster, officials spraying water to clean up the sticky mess only spread the molasses further. Pumping salt water from the harbor caused the molasses to foam, compounding the problem.

Immediately after the disaster, officials spraying water to clean up the sticky mess only spread the molasses further. Pumping salt water from the harbor caused the molasses to foam, compounding the problem.

Accounts from local residents say people could smell molasses in the neighborhood for decades after the disaster.

The cause of the tank’s rupture was never determined decisively. The owner of the tank, the Purity Distilling Company, blamed the disaster on explosives planted by anarchists. After extensive litigation, the company was held responsible for not caring for the tank responsibly. The company paid more than $1 million in damages.

As an aside, “Boston Molasses Disaster” is also the name of a local jam band.

As an aside, “Boston Molasses Disaster” is also the name of a local jam band.

Sources:

Massachusetts Historical Society

Eric Postpischil’s Molasses Disaster Pages

Tags: Massachusetts

A memorial erected on the 300th anniversary of Boston’s settlement honors the city’s founders.

A memorial erected on the 300th anniversary of Boston’s settlement honors the city’s founders.

The 1930 Founders’ Memorial on Boston Common, near the corner of Beacon and Spruce streets, features a bronze bas-relief on its south face depicting the arrival of the city’s Puritan settlers.

In the scene William Blackstone, the first settler of Boston, is greeting John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Native Americans watch the scene, which includes Ann Pollard, the first white woman to land in Boston. An allegorical figure representing Boston watches from the far right.

On the north face, facing Beacon Street, a dedication reads, “”In gratitude to God for the blessings enjoyed under a free government, the City of Boston has erected this memorial on the three hundredth anniversary of its founding – September 17th, 1630-1930.”

On the north face, facing Beacon Street, a dedication reads, “”In gratitude to God for the blessings enjoyed under a free government, the City of Boston has erected this memorial on the three hundredth anniversary of its founding – September 17th, 1630-1930.”

Above this dedication, two quotes from early settlers have been inscribed. The first composed by Winthrop during the long Atlantic voyage, reads, “For wee must consider that wee shall be as a citty upon a hill. The eies of all people are uppon us, soe that if wee shall deale falsely with our God in this work…wee shall be made a story and a byword through the world.”

The second quote is from a history of Plymouth colony by governor William Bradford: “Thus out of smalle beginnings, greater things have been produced by His hand that made all things out of nothing…and as one small candle may light a thousand, so the light here kindled hath shone to many, yea, in some sorte to our whole nation.”

William Blackstone (also spelled Blaxton), the first English settler in Boston, was an Anglican minister. With a keen eye for valuable real estate, he lived on today’s Beacon Hill and Boston Common, and sold the land for the common to the Puritan settlers. After religious and political disagreements, he moved south and became the first settler in today’s Rhode Island. The Blackstone River is named after him.

William Blackstone (also spelled Blaxton), the first English settler in Boston, was an Anglican minister. With a keen eye for valuable real estate, he lived on today’s Beacon Hill and Boston Common, and sold the land for the common to the Puritan settlers. After religious and political disagreements, he moved south and became the first settler in today’s Rhode Island. The Blackstone River is named after him.

The monument was created by sculptor John Francis Paramino, who also provided a number of public memorials in Boston.

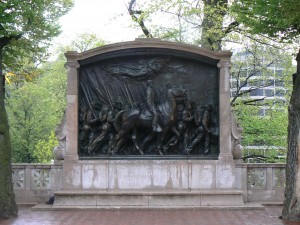

Massachusetts honors a largely African American Civil War regiment with a notable Saint-Gaudens monument on Boston Common.

Massachusetts honors a largely African American Civil War regiment with a notable Saint-Gaudens monument on Boston Common.

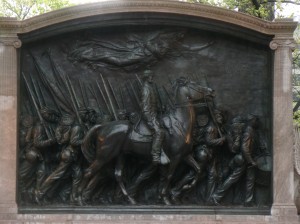

The Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, dedicated in 1897 near the corner of Beacon and Park streets, honors Shaw and the members of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The unit blended white officers with African American troops recruited from several states and Canada.

Shaw and other members of the 54th died during an assault on Fort Wagner, which stood near Charleston, S.C.

The front (north) face of the monument features a large bas-relief illustrating the regiment’s departure from Boston on May 28, 1863. Shaw, the regiment’s commander, is depicted on horseback while the regiment, guided by an angel, marches alongside him.

Under the relief, a dedication reads, “Robert Gould Shaw. Colonel of the Fifty Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Infantry. Born in Boston 10 October MDCCCXXXVII (1837). Killed while leading the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, 18 July MDCCCLXIII (1863).

Under the relief, a dedication reads, “Robert Gould Shaw. Colonel of the Fifty Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Infantry. Born in Boston 10 October MDCCCXXXVII (1837). Killed while leading the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, 18 July MDCCCLXIII (1863).

Under the dedication is a verse from a poem, “Memoriae Positum,” by James Russell Lowell.

The monument also features two large eagles on its east and west sides. Modern-era granite markers on the site provide information about the monument and its sculptor.

On the south side of the monument, a lengthy dedication by Harvard president Charles W. Eliot provides information about the regiment and praises its African American soldiers for having the “pride, courage and devotion of the patriot soldier.”

The names of five regimental officers killed in the war (two during the Fort Wagner assault) are inscribed on the monument and surrounded by wreaths. The names of 62 soldiers killed in the Fort Wagner assault were added to the monument’s south face during a 1982 restoration.

The names of five regimental officers killed in the war (two during the Fort Wagner assault) are inscribed on the monument and surrounded by wreaths. The names of 62 soldiers killed in the Fort Wagner assault were added to the monument’s south face during a 1982 restoration.

The monument was created by noted sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whose other famous works include a standing Lincoln statue in Chicago as well as statues of Union general William T. Sherman and Admiral David Farragut in New York.

The regiment, which had trained outside the city, passed by the monument’s location during their march to the Boston Harbor ships that would take them south. The unit’s route passed the Massachusetts state house (across from the monument) and the Shaw family home at 44 Beacon Street. Shaw raised his sword as he passed the home.

After the fighting at Fort Wagner, the Confederates buried Shaw and his troops in a common grave, a move that defied the honorable treatment traditionally provided to deceased officers. Shaw’s family declined later offers to have him exhumed, saying they were honored that he was buried with his troops.

After the fighting at Fort Wagner, the Confederates buried Shaw and his troops in a common grave, a move that defied the honorable treatment traditionally provided to deceased officers. Shaw’s family declined later offers to have him exhumed, saying they were honored that he was buried with his troops.

Tags: Massachusetts