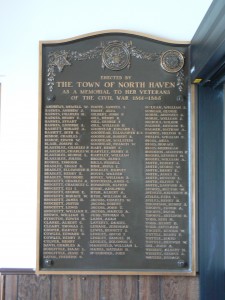

North Haven honors local veterans with a collection of monuments on the green across from its 1886 Memorial Town Hall.

North Haven honors local veterans with a collection of monuments on the green across from its 1886 Memorial Town Hall.

Near the southern end of the green, North Haven honors Civil War veterans with a 1905 monument that features an 1867 Rodman gun mounted on a stone base. A dedication on the base’s front (west) face reads, “Erected by the town of North Haven as a tribute to the valor of her sons who on land and sea fought in the Civil War to preserve the Union.”

The east face lists the monument’s 1905 dedication date and honors the battles of Cedar Mountain, Fort Wagner, Fredericksburg, Fort Gregg, and Petersburg (all in Virginia).

The cannon was manufactured in 1867 at the Fort Pitt Foundry in Pittsburgh, and was one of four installed at Lighthouse Point in New Haven. Another Lighthouse Point cannon stands as a Civil War monument on the East Haven green. Another that stood near Milford’s Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument was lost to a World War II scrap drive, and the fate of the fourth cannon isn’t readily known.

The cannon was manufactured in 1867 at the Fort Pitt Foundry in Pittsburgh, and was one of four installed at Lighthouse Point in New Haven. Another Lighthouse Point cannon stands as a Civil War monument on the East Haven green. Another that stood near Milford’s Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument was lost to a World War II scrap drive, and the fate of the fourth cannon isn’t readily known.

A pyramid of replica cannonballs stands near the monument.

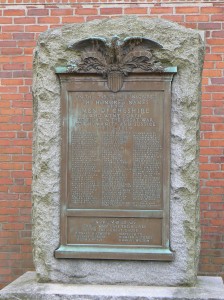

Also north of the Civil War monument are memorials to local veterans who served in Vietnam and Korea. Those wars are commemorated with Honor Roll plaques mounted on granite monuments.

Moving farther north, we find North Haven’s World War II monument, which features two large Honor Roll plaques listing local veterans in 10 columns. The right side of the monument also lists seven residents killed in the conflict as well as one who was missing in action. The left side has a plaque honoring nine residents who were held as prisoners of war.

Moving farther north, we find North Haven’s World War II monument, which features two large Honor Roll plaques listing local veterans in 10 columns. The right side of the monument also lists seven residents killed in the conflict as well as one who was missing in action. The left side has a plaque honoring nine residents who were held as prisoners of war.

Across Church Street stands North Haven’s 1886 Memorial Town Hall, which was the town’s first tribute to its Civil War Veterans. Just inside the lobby are plaques listing local veterans who served in the Civil War and World War I, and a monument honoring all war veterans stands in front of the building.

The plaque listing residents who served in the Civil War is a later replacement for a marble plaque (now owned by the North Haven Historical Society) listing residents who died in the war.

The erection of a memorial hall and a Civil War monument reflects a debate held in several Connecticut towns whether to honor veterans with a monument or a civic building. As was the case in Madison, monument supporters continued campaigning well after a town hall had been constructed, and the town eventually received both.

The erection of a memorial hall and a Civil War monument reflects a debate held in several Connecticut towns whether to honor veterans with a monument or a civic building. As was the case in Madison, monument supporters continued campaigning well after a town hall had been constructed, and the town eventually received both.

Tags: North Haven

Cheshire honors Civil War veterans with an 1866 obelisk that is among the state’s earliest monuments to that war.

Cheshire honors Civil War veterans with an 1866 obelisk that is among the state’s earliest monuments to that war.

The Soldiers’ Monument stands on the Cheshire Green, in front of the town’s 1827 First Congregational Church and across the street from Town Hall.

A dedication on the monument’s front (east) face reads, “Erected to the memory of those who enlisted from the town of Cheshire in the Civil War, 1861-1865.” Below the dedication, 27 names are listed.

The monument’s other faces also bear bronze plaques, each listing 33 names of local Civil War veterans.

The reference to the “Civil War” on the dedication reflects the facts that the plaques were attached to the monument in 1916. Most late 19th century monuments refer to the conflict as the “War of the Rebellion” or describe preserving the Union. The term “civil war” was adopted in the early 20th century.

At its 1866 dedication, the monument originally listed 14 names. As veterans died after the war, their names were incised into the monument. In 1916, the bronze plaques were created and the monument was rededicated.

At its 1866 dedication, the monument originally listed 14 names. As veterans died after the war, their names were incised into the monument. In 1916, the bronze plaques were created and the monument was rededicated.

The base of the monument’s north face is inscribed with “Foote,” a reference to Admiral Andrew Hull Foote, who commanded Navy forces who helped with the capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in Tennessee, as well as Island No. 10 on the Mississippi River. Foote’s grandfather was a pastor of the Congregational Church, and his father served as a U.S. senator and governor of Connecticut.

The base of the monument’s south face honors Abraham Lincoln with the inscription of his last name.

Cheshire’s Civil War monument was dedicated in July of 1866, making only the 1863 Soldiers’ Monument in Kensington (believed to be the oldest in the country) and the January 1866 Soldiers’ Monument in Bristol (and perhaps the undated Civil War monument in Plymouth) as older. Civil War monuments in Northfield and North Branford were also dedicated later in 1866.

The fact that all of these monuments are obelisks reflects the evolution of war memorials from cemetery monuments.

The fact that all of these monuments are obelisks reflects the evolution of war memorials from cemetery monuments.

Across the street from the monument, a 1990 memorial honors Cheshire’s war veterans. The memorial is not far from the town’s World War I monument, which lists local veterans in three columns. A separate section highlights six veterans who were killed in the conflict.

Tags: Cheshire

Milford honors its founders and Native Americans with an 1889 bridge on the site of the city’s first mill.

Milford honors its founders and Native Americans with an 1889 bridge on the site of the city’s first mill.

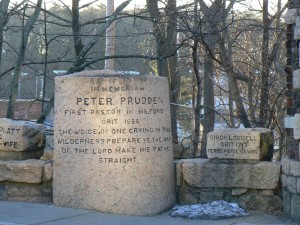

The Memorial Bridge, across the Wepawaug River along today’s New Haven Avenue, was built as part of Milford’s 250th anniversary celebration. The bridge features a tower and 29 stones inscribed with the names of local settlers, as well as an eclectic collection of local artifacts.

The bridge’s north and south copings are marked with large pink granite stones inscribed with the name of an original settler, as well as the name of his wife and date of his death.

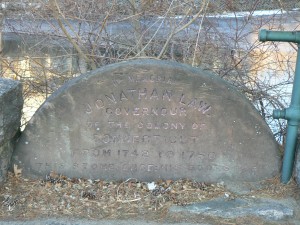

Next to the doorway leading into the 29-foot tower is a large stone inscribed with a dedication to Robert Treat, an early Milford settler who served as governor of the Connecticut colony. A later governor, Jonathan Law, is honored with a stone (the former doorstep of his home) on the bridge’s north coping.

Next to the doorway leading into the 29-foot tower is a large stone inscribed with a dedication to Robert Treat, an early Milford settler who served as governor of the Connecticut colony. A later governor, Jonathan Law, is honored with a stone (the former doorstep of his home) on the bridge’s north coping.

The front entrance also honors the area’s original settlers from the Wepawaug nation with a stylized Native American portrait over the doorway and a representation of the mark by which Ansantawae, the nation’s sachem, signed the deed for the purchase of Milford.

On the doorway, a knocker was taken from the front door of a home with a porch from which George Whitfield, a founder of the Plymouth Church, preached. The doorway also features the hanger for a lantern that has been lost over the years.

The bridge’s buttress features a stone from the town’s first mill.

The bridge’s buttress features a stone from the town’s first mill.

A stone just north of the bridge tower honors Milford police officer Daniel S. Wasson, who was killed in the line of duty in 1987 during a late-night traffic stop.

Local officials commissioned the bridge in 1889 to honor Milford’s original settlers, in part because the settlers’ final resting places aren’t known. As settlers passed away, they were buried in what would become Milford Cemetery. Those graves were either unmarked, or marked with wooden headstones that were eventually lost to time.

A hundred years later, officials marking the city’s 350th anniversary erected a plaque listing the names of early settlers who had been omitted from the bridge.

Tags: Milford

Kent honors its Civil War veterans with an 1885 obelisk in the intersection of North Main Street (Route 7) and Bridge Street (Route 341).

Kent honors its Civil War veterans with an 1885 obelisk in the intersection of North Main Street (Route 7) and Bridge Street (Route 341).

The simple obelisk stands slightly off-center in the middle of Route 7, protected from traffic only by four planters and a low curb.

A dedication on the monument’s front (north) face reads, “A tribute of honor and gratitude to her citizens who fought for liberty and Union, 1861-1865”. The bottom of the base is inscribed with the words, “Erected by the people of Kent, 1885.”

The Connecticut shield is also engraved in the monument’s north face.

The monument’s other faces are free of engraving or ornamentation.

The obelisk was originally built closer to the true center of the intersection, but was shifted to the west during a 1924 widening of Route 7.

Information about the monument’s designer has not come to light, but the Kent obelisk has been attributed to Robert W. Hill, who designed the nearly identical 1871 Soldiers’ Monument in Woodbury. If Hill wasn’t responsible for the Kent monument, someone ripped off his Woodbury design.

Tags: Kent

A 1905 monument marks the former location of Hartford’s legendary Charter Oak tree.

A 1905 monument marks the former location of Hartford’s legendary Charter Oak tree.

The Charter Oak, a noted landmark and symbol for Hartford and Connecticut, was supposedly the hiding place of the royal charter granting legitimacy to the colony of Connecticut.

The monument, not far from where the Charter Oak stood, is at the corner of today’s Charter Oak Avenue and Charter Oak Place. The monument is a round column topped with a globe that is supported by a base with four whales and sea shells, which we assume represent Connecticut’s maritime history.

A dedication on the monument’s front (west) face reads, “Near this spot stood the Charter Oak, memorable in the history of the colony of Connecticut as the hiding place of the charter October 31, 1687. The tree fell August 21, 1856.”

The east face of the monument is inscribed with its 1905 dedication date and credits the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut 1633-1775 for erecting the monument.

The Charter Oak legend is based on a 1687 incident that followed a political dispute over whether the fledgling Connecticut colony would be consolidated into a unified colony covering the New England states. During negotiations over the dispute, Connecticut’s royal charter was removed from the meeting room and, according to the legend, was hidden in large white oak tree that would become known as the Charter Oak.

The Charter Oak legend is based on a 1687 incident that followed a political dispute over whether the fledgling Connecticut colony would be consolidated into a unified colony covering the New England states. During negotiations over the dispute, Connecticut’s royal charter was removed from the meeting room and, according to the legend, was hidden in large white oak tree that would become known as the Charter Oak.

The Charter Oak tree, which grew to have a base with a diameter circumference of 33 feet, fell after a storm in 1856. Wood from the tree was used to make the elaborate seat used by the president of the state senate and a large number of other objects displayed in the capitol building.

As you can see in the vintage postcard near the bottom of this post, the small marble marker engraved with the date the Charter Oak fell used to be part of a wall along Charter Oak Place. It was later incorporated into the brick apartment building. (The postcard was mailed in 1911 from Hartford to East Douglas, Mass.)

The Charter Oak, which remains a common Connecticut symbol, was depicted on the back of the state’s quarter in 2000.

Tags: Hartford

During a break in the wet snow blanketing southern Connecticut today, we again visited the 1888 Soldiers’ and Sailor’s Monument honoring Milford’s Civil War veterans.

During a break in the wet snow blanketing southern Connecticut today, we again visited the 1888 Soldiers’ and Sailor’s Monument honoring Milford’s Civil War veterans.

Unlike the tulips and holiday lights we saw on earlier visits to the monument, wet snow clung to much of the monument, including the eagle on the front (east) face and the infantry figure atop the monument.

A bit west of the Soldiers’ and Sailor’s Monument, the bronze figures on Milford’s Korea and Vietnam War Monument were also covered with snow.

Tags: Milford

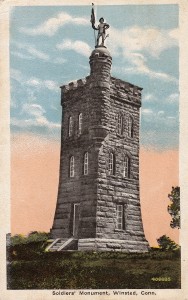

Winchester honors its Civil War veterans with a magnificent 64-foot medieval tower on a hill overlooking the town.

Winchester honors its Civil War veterans with a magnificent 64-foot medieval tower on a hill overlooking the town.

The Winchester Soldiers’ Monument, dedicated in 1890, is the largest feature in a Crown Street park. The monument features a corner tower topped by an eight-foot bronze standard-bearer.

A granite archway along Crown Street, in the Winsted section of Winchester, stands in front of a long stairway that leads visitors to the monument tower. The archway bears the years of the Civil War.

A marker on the front (west) face of the monument reads “Soldiers Memorial.” Below the marker, a small plaque honors the monument’s inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

The monument’s three-story interior, which we have not yet visited, includes a dedication plaque reading, “Erected by the citizens of Winchester in recognition of their obligation to the loyal men who represented them during the War of the Rebellion, whose names are herein perpetuated in grateful remembrance of their patriotic service, 1861 – 1865.”

The monument’s interior also includes markers listing the approximately 300 local residents who served in the war. The interior also includes a fireplace.

The monument’s interior also includes markers listing the approximately 300 local residents who served in the war. The interior also includes a fireplace.

A bronze door that depicted scenes from the war was lost to a World War II scrap drive. During World War II, the monument was used as an observation tower. A wooden structure was added to the roof, and the site was electrified.

The tower is also used to display Christmas lights, which were visible atop the monument during our visit in late January.

The park surrounding the monument also includes two cannons, a fountain/planter and a bulletin board with helpful information describing the monument and its history.

The monument was designed by architect Robert W. Hill, who was also responsible for several state armories, opera houses in New Britain and Thomaston, the Litchfield county courthouse, and other public and private buildings.

The standard-bearer was created by George E. Bissell, whose other creations included the Soldiers’ Monument in Waterbury, and the Civil War Monument in Salisbury.

The Winchester monument was been repaired several times in its history. Broken windows were replaced in the late 1970s, and since the early 1990s, a municipal commission has overseen the ongoing restoration of the monument.

The Winchester monument was been repaired several times in its history. Broken windows were replaced in the late 1970s, and since the early 1990s, a municipal commission has overseen the ongoing restoration of the monument.

A number of road signs helpfully direct visitors from downtown to the monument, which is open to the public during the afternoons of Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day and Veteran’s Day.

The horizontal, black-and-white postcard near the bottom of this post was mailed from Winsted in 1907 to Illinois. The postmark on the color postcard, which was mailed to Bridgeport, was damaged when someone removed the stamp.

More information about the monument and its restoration, including interior views, can be seen at the Soldiers’ Monument and Memorial Park website.

More information about the monument and its restoration, including interior views, can be seen at the Soldiers’ Monument and Memorial Park website.

Tags: Winsted

Ansonia honors the hiding of provisions from invading British troops with a monument in its Pork Hollow neighborhood.

Ansonia honors the hiding of provisions from invading British troops with a monument in its Pork Hollow neighborhood.

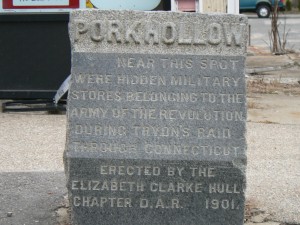

The monument, near the corner of Wakelee Avenue and Pork Hollow Street, was dedicated in 1901 to commemorate an 1777 incident during which military supplies and food were hidden from British troops.

The provisions, stored in a riverfront warehouse near today’s downtown Derby, were destined for Continental troops fighting in New York City. When British General William Tryon attempted to seize the supplies, they were removed from the warehouse and hidden in the woods.

A granite marker erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution summarizes the incident with a dedication on its front (west) face reading, “Pork Hollow. Near this spot where hidden military stores belonging to the army of the Revolution during Tryon’s raid through Connecticut. Erected by the Elizabeth Clarke Hull chapter D.A.R. 1901.”

Elizabeth Clarke Hull was a grandmother of Commodore Isaac Hull, a Derby native who commanded the battleship U.S.S. Constitution during the War of 1812.

Elizabeth Clarke Hull was a grandmother of Commodore Isaac Hull, a Derby native who commanded the battleship U.S.S. Constitution during the War of 1812.

We thank Marietta for suggesting the Pork Hollow site.

Sources: Electronic Valley: Derby History Quiz

Report of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Volume 10

Tags: Ansonia

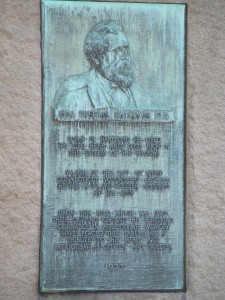

Hartford honors a “typical volunteer soldier” of the Civil War with a monument near the site where many regiments trained before heading south.

Hartford honors a “typical volunteer soldier” of the Civil War with a monument near the site where many regiments trained before heading south.

The Griffin A. Stedman monument in the city’s Barry Square neighborhood stands on Campfield Avenue, which was named for the fields in which several of Connecticut’s volunteer infantry regiments trained.

Stedman, a Hartford native, joined the 14th Regiment in 1861 and was appointed a captain in the 5th Regiment. He was promoted four times during the war, and was wounded at the Battle of Antietam. He reached the rank of brigadier general before being killed at Petersburg, Va., at the age of 26.

Stedman is buried in Hartford’s Cedar Hill Cemetery.

The monument, dedicated in 1900, honors Stedman and the Connecticut regiments who camped in the field near the monument before starting their Civil War service. A dedication on the front (west) face reads, “Griffin A. Steadman, typical volunteer soldier of the Civil War. Captain, Major, Lieutenant Colonel, Colonel, Brigadier General. Born at Hartford, Conn., January 6, 1838. Killed at Petersburg, Va., August 5, 1864.” The west face also displays crossed rifles representing the infantry near the base and crossed swords, representing the cavalry, near the top of the base.

Gen. Stedman stands atop the monument, facing west with binoculars in his right hand and his left resting near his sword.

Gen. Stedman stands atop the monument, facing west with binoculars in his right hand and his left resting near his sword.

A bronze plaque on the south face describes the location of the former regimental camp fields, and the east face bears a bronze Connecticut shield. The north face has a bronze plaque honoring the units that trained in Hartford (the 5th, 8th, 10th, 14th, 16th, 22nd and 25th). The corners of the monument’s base bear pyramids of concrete cannon balls.

The monument was sculpted by Frederick Moynihan, who also created the JEB Stuart statue along Richmond’s Monument Avenue and two monuments at the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park.

The Stedman monument stands near the corner of Campfield Avenue and Bond Street, next to St. Augustine Church. A marker in the field honors Matthew Arace, a Hartford police officer killed in a 2006 automobile accident. Sgt. Arace, who did community work in the Barry Square neighborhood, is also honored with a bridge on Interstate 91 in Hartford.

The Stedman monument stands near the corner of Campfield Avenue and Bond Street, next to St. Augustine Church. A marker in the field honors Matthew Arace, a Hartford police officer killed in a 2006 automobile accident. Sgt. Arace, who did community work in the Barry Square neighborhood, is also honored with a bridge on Interstate 91 in Hartford.

Across Campfield Avenue, a bronze plaque mounted on a granite slab honors Thomas McManus, a Hartford native and Civil War veteran who served as a major in the 25th Regiment. He was also a judge, a member of Connecticut’s General Assembly and director of the state prison at Wethersfield.

McManus was also active in veterans’ affairs after the war, and was one of the main organizers of the Stedman monument effort. McManus died in 1913, and his fellow 25th Regiment veterans honored him with the plaque in 1923.

Tags: Hartford

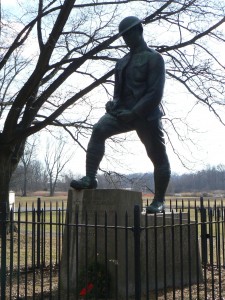

A World War I recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross is honored with a monument in New Haven’s West River Memorial Park.

A World War I recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross is honored with a monument in New Haven’s West River Memorial Park.

Timothy Ahearn, an infantry corporal, was honored for actions on October 27, 1918, near Verdun, France. After the officers and sergeants of his company had become casualties, Cpl. Ahern assumed command and organized the remnants of his unit. He led the men through heavy fighting, and, later that day, rescued a wounded officer while facing machine gun fire.

The monument, dedicated in 1937 as part of the New Deal’s Federal Art Project, depicts Ahern writing a note to regimental commanders describing his actions and requesting replacements.

A dedication on the front (north) face of the monument’s base includes biographical information about Ahearn, and adds the inscription, “He best exemplified the spirit of the enlisted men of the Yankee division.”

A dedication on the front (north) face of the monument’s base includes biographical information about Ahearn, and adds the inscription, “He best exemplified the spirit of the enlisted men of the Yankee division.”

The statue, near the intersection of Routes 10 (Ella T. Grasso Blvd.) and 34 (Derby Ave.) was created by sculptor Karl Lang, who was also responsible for the Veterans’ Memorial Flagpole in Darien’s Spring Grove Cemetery.

The east and west sides of the monument’s base include additional information about Cpl. Ahearn’s bravery in combat.

The south side of the base has a bronze plaque describing the monument and listing the committee and the local veterans’ organizations responsible for its construction.

Tags: New Haven