Hartford’s Spanish-American War veterans are honored with an allegorical monument in the city’s Bushnell Park.

Hartford’s Spanish-American War veterans are honored with an allegorical monument in the city’s Bushnell Park.

The Spirit of Victory monument, near the intersection of Elm and Trinity streets, features a winged figure standing atop the bow of a ship with an eagle figurehead that we assume represents the United States.

Victory stands with a torch in her raised right arm, and her left hand holds a shield decorated with the United States flag.

The base of the monument is a large granite base with inscriptions on its front (west) face. The dedication, which is split between the north and south sides of the monument, reads, “To commemorate the valor and patriotism of the Hartford men/Who served their country in the war with Spain 1898.”

The bench is also decorated with two bronze plaques. On the north side, a muscular sailor is loading ammunition, and on the south side, an infantryman kneels with a rifle.

The bench is also decorated with two bronze plaques. On the north side, a muscular sailor is loading ammunition, and on the south side, an infantryman kneels with a rifle.

The back of the monument has a small plaque listing its 1927 dedication date, along with the names of two mayors and eight councilmen who served when the monument was planned and dedicated.

The Spirit of Victory was created by noted sculptor Evelyn Beatrice Longman, who is perhaps best known for Electricity and the Spirit of Communication, the “golden boy” statue that served as a symbol of AT&T for many years. Longman also created decorative elements on the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, and her Connecticut works include the World War monuments in Naugatuck and Windsor.

Longman’s signature is inscribed atop the bow of the ship, near Victory’s feet.

Longman’s signature is inscribed atop the bow of the ship, near Victory’s feet.

From the Spirit of Victory, you can see the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch to the northwest and the state capitol building to the west.

Tags: Hartford

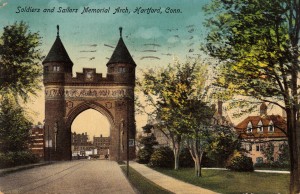

A Bushnell Park archway with two towers and a life-sized frieze honors Hartford’s Civil War veterans.

A Bushnell Park archway with two towers and a life-sized frieze honors Hartford’s Civil War veterans.

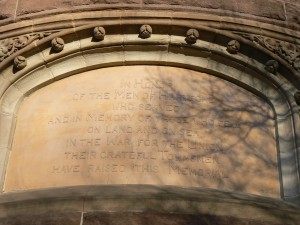

The 1886 Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch features two medieval towers alongside an archway that spans Trinity Street. A dedication on the east tower (the right tower as you stand with your back to the Capitol building) reads, “In honor of the men of Hartford who served, and in memory of those who fell on land and on sea in the war for the Union, their grateful townsmen have raised this memorial.”

The west tower has a dedication plaque reading, “During the Civil War, 1861 – 1865, more than 4,000 men of Hartford bore arms in the national cause, nearly 400 of whom died in the service. Erected 1885.”

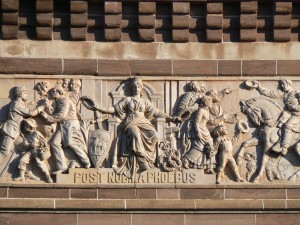

The monument is dominated by the frieze depicting a variety of scenes that took place during and after the war. The south frieze, by sculptor Caspar Buberl, illustrates the return of Hartford’s soldiers after the war. On the eastern (your right) side of the frieze, soldiers and sailors are leaving a ship and are being greeted by family members throughout the scene.

The monument is dominated by the frieze depicting a variety of scenes that took place during and after the war. The south frieze, by sculptor Caspar Buberl, illustrates the return of Hartford’s soldiers after the war. On the eastern (your right) side of the frieze, soldiers and sailors are leaving a ship and are being greeted by family members throughout the scene.

The allegorical figure in the center of the scene represents Hartford. At her feet, the arch is inscribed with the city’s Latin motto, post nubila phoebus, which translates as “after clouds, the sun.” The motto also reflects joy and optimism following the dark days of the Civil War.

The north frieze, by sculptor Samuel Kitson, depicts battle scenes from the war. Ulysses S. Grant is depicted on the far right side of the frieze.

Just below the friezes, decorative elements honor the infantry (crossed rifles) and cavalry (crossed swords) on the south side, and the Navy (the admittedly obvious anchor) and the artillery service (crossed cannons) on the north side.

Just below the friezes, decorative elements honor the infantry (crossed rifles) and cavalry (crossed swords) on the south side, and the Navy (the admittedly obvious anchor) and the artillery service (crossed cannons) on the north side.

The two turrets are also decorated with six figures representing the variety of occupations Connecticut’s veterans left behind as they ventured south to fight in the Civil War, and are topped with angels providing a musical accompaniment to the return of Hartford’s soldiers.

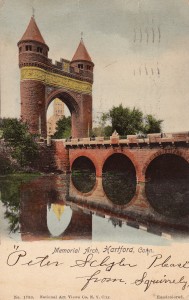

As you can see in the vintage postcards near the bottom of this post, the monument originally stood at the southern end of a bridge over the Park River. The river was diverted underground during the 1940s, but the bridge parapets can be seen just north of the archway.

The monument underwent an extensive renovation in 1988, during which a plaque was attached to the west tower to honor the contributions of African American soldiers in the Civil War. In addition, the terra cotta angels atop the two towers were replaced with bronze replicas.

The monument underwent an extensive renovation in 1988, during which a plaque was attached to the west tower to honor the contributions of African American soldiers in the Civil War. In addition, the terra cotta angels atop the two towers were replaced with bronze replicas.

The monument was designed by George Keller, a leading memorial architect who also created the Soldiers’ National Monument in Gettysburg as well as the U.S. Soldier Monument at Antietam. After his death in 1935, the cremated remains of Keller and his wife, Mary, were interred in the arch’s east tower.

Tags: Hartford

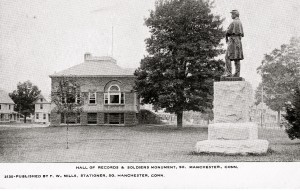

Manchester’s Civil War veterans are honored with a monument in the city’s Center Memorial Park.

Manchester’s Civil War veterans are honored with a monument in the city’s Center Memorial Park.

The monument features a bronze infantryman standing atop a granite base inscribed with the Connecticut and United States shields. A dedication on the front (northeast) face reads, “In memory of the soldiers of Manchester who died in the war of the rebellion 1861-1865.”

The monument’s base is rough-hewn, and free from other inscriptions or dedications. The figure was sculpted by Charles Conrads, the in-house sculptor for James G. Batterson, the Hartford industrialist who supplied many Civil War monuments in the state.

As you can see in the vintage postcard near the bottom of this post, the monument originally faced southeast, toward the park. In 1965, it was turned around to face the intersection of Main Street (Route 83) and Center Street (Routes 6 and 44). The Hall of Records building cited on the postcard serves today as Manchester Probate Court.

As you can see in the vintage postcard near the bottom of this post, the monument originally faced southeast, toward the park. In 1965, it was turned around to face the intersection of Main Street (Route 83) and Center Street (Routes 6 and 44). The Hall of Records building cited on the postcard serves today as Manchester Probate Court.

Manchester’s Soldiers’ Monument was dedicated on Sept. 17, 1877, the 15th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, and was cleaned before a 2005 rededication.

A Spanish-American War monument stands a short walking distance west of the Soldiers’ Monument, near the Probate Court. A dedication near the monument’s base reads, “A memorial to the boys of Manchester, Conn., who volunteered and served their country in the Spanish American War.”

The Cheney family operated one of the country’s leading silk mills in South Manchester, and their name decorates many civic buildings and landmarks in the city. Three family members served in the Spanish-American War, and one, Ward C. Cheney, was killed while fighting in the Philippines in 1900.

About a half-mile north of the Soldiers’ Monument is Manchester’s World War I monument, which stands outside Manchester Memorial Hospital. The monument features a bronze plaque mounted on a boulder near the hospital’s Haynes Street entrance.

About a half-mile north of the Soldiers’ Monument is Manchester’s World War I monument, which stands outside Manchester Memorial Hospital. The monument features a bronze plaque mounted on a boulder near the hospital’s Haynes Street entrance.

A dedication on the front (north) face reads, “This tablet is erected in memory of these men of Manchester who made the supreme sacrifice in the World War 1917-1918.” Below the dedication, the monument lists the names of 45 residents killed in the conflict.

The hospital was built in 1920, in part as a response to the 1918 influenza outbreak, and was dedicated to World War I veterans. In 1970, it was rededicated to honor all war veterans.

Source: Manchester Historical Society: Veterans Memorials

Source: Manchester Historical Society: Veterans Memorials

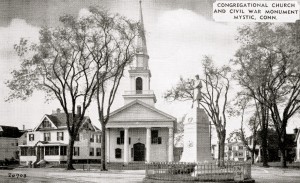

Mystic’s Civil War Veterans are honored with an 1883 monument on a downtown traffic island.

Mystic’s Civil War Veterans are honored with an 1883 monument on a downtown traffic island.

The monument, featuring an infantry soldier standing atop a granite base, sits near the intersections of East Main Street and Broadway Avenue. A dedication on its front (northwest) face reads, “Dedicated to the brave sons of Mystic who offered their lives to their country in the war of the rebellion, 1861-1865.”

Connecticut and United States seals are also inscribed into the front face, which also features a wreath and lists the Battle of Antietam (near Sharpsburg, Md).

The northwest face lists the battle of Port Hudson, La., while the northeast face lists the battle of Gettysburg and the southeast face lists the battle of Drury’s Bluff, (Va.). Other than ornamental wreathes near the top of the pedestal, the monument is relatively subdued.

The northwest face lists the battle of Port Hudson, La., while the northeast face lists the battle of Gettysburg and the southeast face lists the battle of Drury’s Bluff, (Va.). Other than ornamental wreathes near the top of the pedestal, the monument is relatively subdued.

Mystic’s monument is also known for a couple of accidents at its 1883 dedication. Several veterans were burned and bruised as they marched near a cannon, loaded with blanks, that was fired despite the vets’ proximity. In addition, a crowded grandstand collapsed, but fortunately this incident did not produce any injuries.

The monument was funded by Charles Henry Mallory, who operated a steamship line in New York. Mallory’s father, Charles, was a wealthy Mystic shipbuilder and whaler.

The postcard near the bottom of this post was mailed from Mystic to Staten Island, N.Y., in August of 1942. The Mystic Congregational Church and the home next to it have a similar appearance today.

The granite for the monument, like that used in many Connecticut Civil War monuments, was quarried in nearby Westerly, R.I.

The fence surrounding the monument is scheduled to be replaced as part of a $1.1 million federal stimulus project to upgrade sidewalks, curbs, lighting and pavement in the downtown area.

The fence surrounding the monument is scheduled to be replaced as part of a $1.1 million federal stimulus project to upgrade sidewalks, curbs, lighting and pavement in the downtown area.

Tags: Mystic

The service of Vietnam veterans from the greater New Haven area is honored with a collection of monuments on New Haven harbor.

The service of Vietnam veterans from the greater New Haven area is honored with a collection of monuments on New Haven harbor.

The 1988 Vietnam memorial consists of two monuments. The smaller of the two is a polished granite slab with a dedication on its front (north) face reading, “This memorial is dedicated in honor of the men and women who served during the Vietnam War from the surrounding cities and towns: New Haven, East Haven, West Haven, North Haven, Hamden, Orange, [and] Woodbridge.”

The slab is also inscribed with five service emblems as well as the Vietnam service medal.

The memorial also features an 11-foot-high, V-shaped monument inscribed with the names of 55 area residents who were killed in the conflict, as well as the names of three men who were prisoners or reported missing.

The memorial also features an 11-foot-high, V-shaped monument inscribed with the names of 55 area residents who were killed in the conflict, as well as the names of three men who were prisoners or reported missing.

The left side of the V-shaped memorial features a bronze depiction of the Vietnam service medal.

The Vietnam memorials were created by sculptors Kenneth Polanski and Frank Pannenborg.

The Vietnam memorial is joined by a polished black granite Korean War monument that features a map of the Korean penisula along with an inscription reading, “In honor of those who served during the Korean War from the greater New Haven area. Forgotten war, forgotten no more. Freedom is not free.”

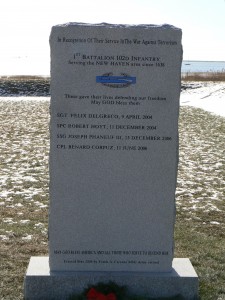

Next to the Korean War memorial is a granite monument honoring service in the global war on terrorism that lists the names of four area residents from the First Battalion, 102nd Infantry who were killed in 2004 or 2006.

Next to the Korean War memorial is a granite monument honoring service in the global war on terrorism that lists the names of four area residents from the First Battalion, 102nd Infantry who were killed in 2004 or 2006.

Another nearby granite monument honors recipients of the Purple Heart medal.

The monuments are part of a waterfront park in the Long Wharf section of New Haven, which was named after piers that were removed when Interstate 95 was constructed. The waterfront near the park was used by British troops leaving New Haven after their 1779 invasion of the city.

Tags: New Haven

The Civil War 21st Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, is honored with a granite obelisk in New London’s Williams Memorial Park.

The Civil War 21st Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, is honored with a granite obelisk in New London’s Williams Memorial Park.

The monument, near the north corner of the park, was dedicated in 1898 to honor the soldiers of the 21st regiment, which was founded in 1862 and recruited primarily members from eastern Connecticut towns.

The front (north) face of the monument is inscribed, “21st. Regt. Conn. Vol.,” and the unit’s service years of 1862-1865 are listed above. A little higher on the north face, a dedication reads, “Erected Sept. 5, 1898, by the state of Connecticut in honor of her citizen soldiers.” (The monument was dedicated on Oct. 20, 1898.)

The north face also lists the unit’s service at the battles of Drewry’s Bluff and Petersburg, and the west face lists battles of Fort Harrison and Richmond. The south face lists the battles of Fair Oaks and Suffolk, and the east face honors the battles of Fredericksburg and Cold Harbor. (All the listed battles took place in Virginia.)

Survivors of the regiment originally voted to place the monument in Willimantic, but a disagreement over the monument’s location (the regiment wanted in front of Town Hall, while local officials preferred the high school grounds) led to an offer to erect the monument at its site in New London.

A wayside marker near the monument, part of a downtown walking tour, describes the significance of the monument and the surrounding neighborhood.

A wayside marker near the monument, part of a downtown walking tour, describes the significance of the monument and the surrounding neighborhood.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: New London

New London honors Nathan Hale and veterans of recent wars with a trio of monuments in its Williams Park.

New London honors Nathan Hale and veterans of recent wars with a trio of monuments in its Williams Park.

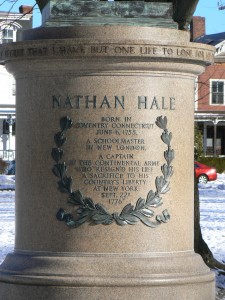

The Nathan Hale statue near the center of the Broad Street park is a 1935 copy of an 1890 statue in New York’s City Hall Park. The statue features Hale, a Connecticut schoolteacher and Continental spy who was hanged in 1776 by British forces at the age of 21, standing atop a round marble base with ropes binding his arms and legs.

An inscription on the front (southwest) face of the monument reads, “Nathan Hale, born in Coventry, Connecticut, June 6, 1755. A schoolmaster in New London, a captain in the Continental Army who resigned his life [as] a sacrifice to his country’s liberty at New York, Sept. 22d 1776.”

The base is also inscribed with Hale’s reported last words, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

The base is also inscribed with Hale’s reported last words, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

The New London statue is a copy of a statue by Frederick William MacMonnies, who many other works include the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park and a statue of Charles Lindberg in a Harvard art museum. The text on the base of the New York edition, which was designed by Stanford White, omits the references to Coventry and New London.

The New London version was cast in 1934 as part of the celebration of Connecticut’s tercentenary in 1935. New London was chosen because Hale had taught school in a small schoolhouse immediately before his service in the American Revolution (the schoolhouse now stands downtown, not far from the Soldiers’ and Sailor’s monument).

Williams Park also honors veterans with a monument featuring a tall stand of shrubbery near the southeast side of the park. The monument, dedicated in 1961 by the Jewish War Veterans, also includes a granite marker inscribed, “Gratefully dedicated to those who gave their lives in the service of our country in order to preserve its ideals of liberty and democracy.”

The middle of the southwest side of the park (along Broad Street) features New London’s monument to its World War II, Korea and Vietnam veterans. The central section of the stone monument lists nearly 125 residents killed in World War II. The left and right sections honor Korea and Vietnam veterans, and both plaques are inscribed with a dedication reading. “This memorial is dedicated to those who served when the call of their country was heard. Self was forgotten. Their deeds and efforts shall never be forgotten.”

The middle of the southwest side of the park (along Broad Street) features New London’s monument to its World War II, Korea and Vietnam veterans. The central section of the stone monument lists nearly 125 residents killed in World War II. The left and right sections honor Korea and Vietnam veterans, and both plaques are inscribed with a dedication reading. “This memorial is dedicated to those who served when the call of their country was heard. Self was forgotten. Their deeds and efforts shall never be forgotten.”

Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Art Inventories Catalog

Tags: New London

One of New London’s three monuments to its Civil War veterans anchors a burial plot in the city’s Cedar Grove Cemetery.

One of New London’s three monuments to its Civil War veterans anchors a burial plot in the city’s Cedar Grove Cemetery.

The ornate monument, near the cemetery’s main entrance, features an infantryman standing atop a multi-staged pedestal. A dedication on the front (north) face of the monument reads, “In memory of our comrades 1861-1865.”

The front face also bears the inscription “Erected by W.W. Perkins Post, No. 47, G.A.R.,” and features a medal symbolizing the Grand Army of the Republic, the post-Civil War veterans’ organization.

The monument is not dated, and information about its construction has not come to light. Based on the ornate decorative elements on the pedestal, Connecticut Historical Society estimates the erection date as about 1900.

The monument stands at the center of a triangular plot featuring 33 headstones of Civil War veterans in two rows. A plot with veterans of more recent conflicts stands south of the Civil War plot, and the prominence of Naval veterans reflects New London’s proud maritime heritage.

A tree just east of the plot was planted by the local Woman’s Relief Corps, a G.A.R. auxiliary organization. A different WRC branch erected the nearby Civil War monument in Stonington.

A tree just east of the plot was planted by the local Woman’s Relief Corps, a G.A.R. auxiliary organization. A different WRC branch erected the nearby Civil War monument in Stonington.

The G.A.R. Post was named after William W. Perkins, a New London resident and first lieutenant in the Tenth Regiment of the Connecticut Volunteer Infantry who was killed while fighting near Kinston, North Carolina.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: New London

A privately funded, 50-foot tall obelisk in downtown New London honors the city’s Civil War veterans.

A privately funded, 50-foot tall obelisk in downtown New London honors the city’s Civil War veterans.

The 1896 Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument features an obelisk with alternating granite bands topped by an allegorical figure representing Peace. A dedication on its front (west) face reads, “Presented to their native city by the sons of Joseph Lawrence, May 6, 1896.” (Joseph Lawrence was a successful New London whaler, and he and his family also founded a number of successful business and philanthropic ventures.)

The west face also bears a bronze plaque with the Connecticut and New London seals.

The dedication on the east face reads, “In memory of New London’s soldiers and sailors who fought in defence of their country. Erected on the site of her first fort, fortified 1691, dismantled 1777.”

The south face honors the city’s proud naval heritage with a statue of a mariner holding a telescope and a rope. The obelisk is engraved with the names of several Civil War, War of 1812 and American Revolution battleships, including the Kearsarge, the Hartford, the Chesapeake, the Constitution and the Trumbull. The south face also lists the word “Defence” as well as the “Don’t Give Up the Ship” motto (the dying words of USS Chesapeake commander James Lawrence (who does not appear to be related to the New London Lawrences)).

The north face features a Union soldier in a traditional monument pose, with an upright rifle between his hands. The obelisk shaft above him is engraved with several Civil War and American Revolution battle sites, including Gettysburg, Port Hudson (La.), Fredericksburg (Va.), Antietam (Md.), Groton and Bunker Hill.

The north face features a Union soldier in a traditional monument pose, with an upright rifle between his hands. The obelisk shaft above him is engraved with several Civil War and American Revolution battle sites, including Gettysburg, Port Hudson (La.), Fredericksburg (Va.), Antietam (Md.), Groton and Bunker Hill.

The west face is also inscribed, “Erected by Sebastian D. Lawrence,” who was one of Joseph Lawrence’s sons and president of the National Whaling Bank. The family also helped found the city’s Lawrence & Memorial Hospital.

The monument is the centerpiece of downtown’s Parade plaza, near the intersection of State and Water streets. Renovations to the Parade have opened views of New London Harbor from the plaza, as well as downtown from Union Station (the building east of the monument). The area also features a red schoolhouse in which Nathan Hale taught (the small red building north of the monument, next to parking garage).

Hale is also honored with a statue in a park we’ll highlight later this week.

Hale is also honored with a statue in a park we’ll highlight later this week.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: New London

Stonington honors its Civil War veterans with a large granite marker in Evergreen Cemetery.

Stonington honors its Civil War veterans with a large granite marker in Evergreen Cemetery.

The boulder-shaped monument was dedicated in 1923, a relatively late date for a Civil War commemoration. A somewhat-faded dedication on the monument’s front (north) face reads, “Erected by the W.R.C. to the brave sons of Stonington who fought in the War of 1861-1865.”

The W.R.C. refers to the Woman’s Relief Corps, an organization affiliated with the Grand Army of the Republic, the Civil War veterans’ group. The monument also features an inscribed GAR logo on its front face.

The monument stands at the center of a veterans’ plot that includes four Civil War headstones at its corners. One honors a soldier who was killed at the battle of Port Hudson, La., in 1863, and another honors one who was killed in Fredericksburg, Va., in 1862. The other two headstones honor veterans who survived the war.

Source: Connecticut Historical Society: Civil War Monuments of Connecticut

Tags: Stonington